Prologue - Wendell Beckwith the Hermit of Whitewater Lake

Earlier this week, I sat down to write a story about hermits—people who’ve chosen to live a solitary life in the Canadian wilderness. But I quickly ran into a problem: it wasn’t simple to capture that idea in a straightforward way.

Some of the most well-known hermits in Canadian history actually interacted with others fairly often. Some did so more than others, but none of them lived in complete isolation. At some point, each person I read about had to rely on others to survive.

Still, I wanted to share their stories, along with a few others. These individuals chose to disconnect from modern society or abandon their familiar surroundings. But even that approach was tricky. I struggled to find a clear, unifying theme. Looking back, maybe that’s not so surprising. We’re all different, and each of us is driven by our own mix of wants, needs, and internal motivations.

So, the theme for this week might feel a bit long-winded. If you’ve read any of my previous posts, especially the recent ones, or listened to any of my stories, you already know I tend to be long-winded too. So maybe it’s not all that surprising.

As best as I can put it, this week’s theme is about looking for answers in nature, in ourselves, and in history. It’s about seeking those answers while living in relative isolation from modern society, but still staying tethered to community in some way.

Before we get into it, let me tell you about the story that inspired this exploration. It’s about a man named Wendell Beckwith, who came to be known as the Hermit of Whitewater Lake. He was born in Wisconsin and, by the mid-1900s, had become a talented inventor and scientist. He held at least 14 patents, many of them from his work with the Parker Pen Company in the 1940s and 1950s.

Despite his success, he experienced turmoil in his personal life. He was married with five children, but something inside him pulled away from family life and conventional society.

In 1955, Beckwith made a drastic choice. He left his wife and children behind in Wisconsin, providing for them through a trust fund, and moved into the Canadian wilderness. Later, he would say that he wanted to dedicate himself to “pure research” in isolation. But it also seems clear that he was running from a life that felt unhappy or confining.

Beckwith’s destination was Best Island on Whitewater Lake, a large lake at the southern edge of what would later become Wabakimi Park. It’s remote, accessible mainly by floatplane or a very long canoe trip.

He arrived there in 1961, having snuck across the Canadian border by homemade canoe catamaran. With him were his wealthy benefactor, Harry Wirth—a San Francisco-based architect—and a woman named Rose Chaltry. Rose worked for Wirth and would later become Beckwith’s friend, part-time companion, and one of the people who helped fund his research.

They made it to Armstrong, Ontario, where they hired a bush pilot to scout possible locations. As they flew over Best Island, they fell in love with it immediately.

Over the next fifteen years or more, Wendell Beckwith poured his energy into creating an elaborate homestead on Best Island. It became a kind of tiny, rustic campus devoted to science and solitude. In time, there were three cabins and a storage workshop, all connected by tidy flagstone paths and bordered by a cedar log fence that was more decorative than defensive.

Each cabin was distinct. Harry Wirth had constructed the main cabin as a cozy log lodge. It featured a massive stone fireplace and an underground icebox for food storage. Beckwith lived in this cabin at first, but he found it too large and inefficient. The fireplace didn’t heat well in the winter, and he thought the whole design was too showy for the focused, pared-down life he wanted. Still, it served as his early living quarters and later became a gathering place for the occasional visitor.

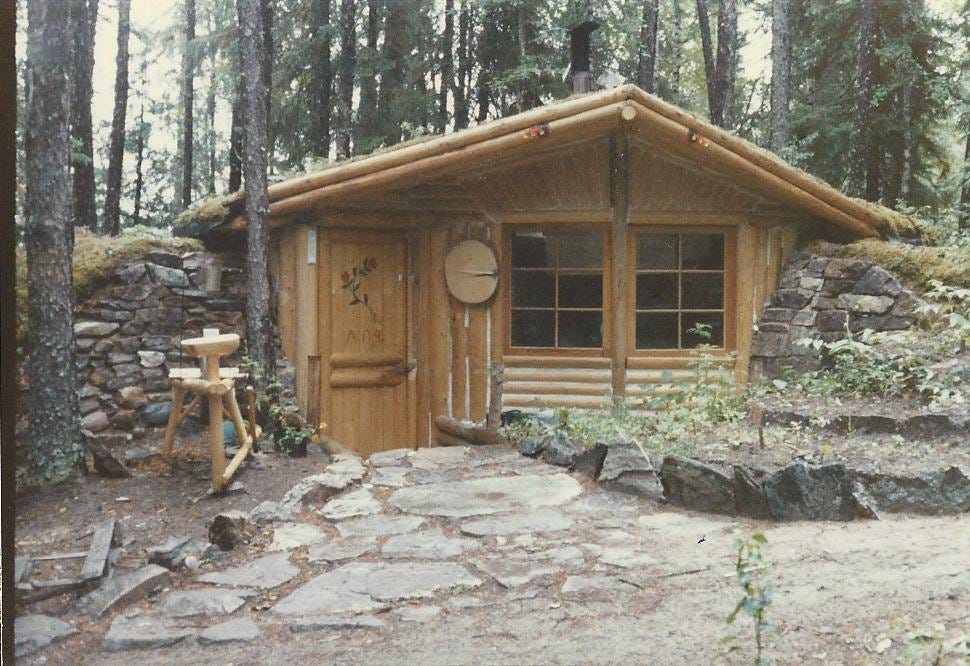

The guest house, later known as Rose’s Cabin, was named after Rose Chaltry, Harry Wirth’s employee and Beckwith’s longtime friend. It was a small, split-level cabin built in the late 1960s, which Rose herself helped assemble when she spent two years there.

But Beckwith’s true masterpiece was the Snail, completed in 1978. It was nothing like a typical log cabin. Built into the side of a hill, the Snail had a circular, spiral-shaped design. It was highly innovative. A skylight in the centre allowed sunlight to warm the space, and a wood stove was set in a sunken floor for better heat retention and was surrounded by large flat rocks that radiated the stove’s heat. Beckwith also added a rotating conical heat shield and a pivoting chimney to maximize efficiency.

Thanks to this clever engineering, the Snail stayed warm through brutal northern winters with surprisingly little firewood. One account says Beckwith only needed to chop wood for about ten minutes a day to keep it heated for 24 hours, even when temperatures dipped below -40°C. Moss chinked the exterior of the Snail, and over time, it sprouted vegetation that helped it blend into the landscape. Beckwith built it with help from local Indigenous friends, who showed him how to use moss as insulation.

All of Beckwith’s structures were crafted with extraordinary care. Visitors later noted that every shingle and flat board was precisely cut. The doors and beams were decorated with intricate carvings. Scattered throughout the cabins were strange scientific contraptions of his own making and several Ojibwe artifacts he had collected. The whole place felt part laboratory, part museum.

Among Beckwith’s inventions were a homemade telescope mounted on the island and a device he called a lunar gun, which he used to chart lunar cycles and predict eclipses. It allowed him to observe the sun and the moon at the same time.

Over time, Beckwith became convinced that Whitewater Lake was the “centre of the universe.” He believed the lake was in perfect geometric alignment, forming a triangle with the Great Pyramids of Egypt and Stonehenge in England. This theory, while not supported by mainstream science, became an obsession for him. He saw repeating patterns of the number pi in nature and geography and believed this remote island held clues to unlocking universal truths.

His pursuit was sincere. For him, solitude was a kind of sanctuary for intellectual freedom. There was no one to interfere and no one to laugh at his ideas. He could spend hours making observations, conducting experiments, and thinking deeply about math, astronomy, and philosophy.

The Thunder Bay Museum, which holds Beckwith’s journals and papers, notes that he developed complex theories about the relationship between time and space during his years on the island. Some astronomers would later suggest that Beckwith identified ideas about the rapid expansion of space—concepts that weren’t widely accepted until decades later.

Although Wendell Beckwith is often remembered as a hermit, he wasn’t completely cut off from human contact. Each summer, he welcomed a small number of visitors. Friends, curious adventurers, and local First Nations people from nearby communities would stop by.

Those who met him remembered a kind, intelligent man with wide-ranging knowledge. He traded and interacted with his Ojibwe and Cree neighbours, who supported him by sharing survival techniques and sometimes helping with heavy tasks. In return, Beckwith shared what he could and offered his skills when appropriate. This mutual respect helped bridge the gap between a solitary scientist and the Indigenous communities that had lived around Whitewater Lake for generations.

Beckwith’s grandson would later say, in a 2020 documentary, that without the support of Indigenous families like the Slipperjacks, his grandfather probably wouldn’t have survived the early years of his wilderness life.

Ruby Slipperjack, who was a child when she came to know Beckwith, said her family accepted him because of his quiet nature. He had a way of watching and learning without asking too many questions. He only offered help when it made sense to do so, and most of the time, he simply blended in. At times, people hardly noticed he was there.

Ruby said that people appreciated Beckwith because he didn't try to change anyone or pass judgment. He wanted to understand the community, and he accepted people for who they were and the way they did things.

The longer Beckwith stayed on Best Island, the more committed he became to minimizing his ecological footprint. He chose only dead trees for building, fished and hunted just enough to meet his basic needs, and relied heavily on growing and foraging his own food. His camp blended into the landscape instead of trying to conquer it. He didn’t clear land or build anything grand or modern-looking. He wanted to live with the land, not on top of it.

Alongside his scientific experiments, Beckwith also recorded daily observations about the natural world. He tracked temperature, wind, atmospheric pressure, and other detailed measurements for years. Long before environmentalism became a global concern, he was one of the early voices to identify signs of climate change.

In August 1980, Wendell Beckwith died of an apparent heart attack on the shore of his beloved Whitewater Lake. He was 65 and had spent nearly 20 years living in the wilderness on Best Island.

After his death, the cabins were left standing, slowly aging under the northern sun and snow. Over time, Whitewater Lake was incorporated into the expanded Wabakimi Provincial Park. The Ontario government now owns Best Island, and Beckwith’s camp is officially park property.

There has been an ongoing debate about what should happen to the structures. Some argue they should be preserved as part of Ontario’s cultural heritage. Others believe that in a wilderness park, man-made buildings—especially ones that are unsafe or falling apart—should be left to crumble and return to the earth.

For a time, the cabin stood like an open-air museum for adventurers. Canoeists who made the journey often stopped at Best Island to peek into Beckwith’s world. In the early 1990s, visitors said the site was mostly intact, almost exactly as Beckwith had left it.

However, by the 2000s, the damage had been inflicted by time and probable vandals. Kevin Callan, an outdoor writer who visited in 1993, reported that not long afterward, items began disappearing. Selfish visitors, seeking souvenirs, took some of Beckwith's handmade tools and notebooks. Natural decay also set in. A storm brought down a large tree onto the main cabin, and by 2011, an inspection found a gaping hole in the roof and damage to the walls.

Thankfully, most of Beckwith’s notes, drawings, and some of his inventions were preserved. Beckwith left instructions for the Ontario government to receive them, and the Ministry of Culture eventually collected them. Today, they’re housed in the Thunder Bay Museum and Archives and are well worth taking the time to visit if you’re in the area.

While scientists who have studied his work haven’t been able to make full sense of it, that might change. With advances in AI and machine learning, it’s possible that one day his notes could reveal discoveries that would have otherwise been lost to time.

It’s fascinating to wonder what Beckwith may have been up to during all those years alone in the wilderness. Is Whitewater Lake really the centre of the universe? Were ancient technologies based on the number pi known to both the Egyptians and the builders of Stonehenge? We may never know. But Beckwith believed the answers were out there, hidden in the natural world, not in labs or lecture halls.

By 2021, the main cabin had fully collapsed into ruins. The Snail cabin still stood, but a hole had formed in its roof, which will eventually lead to collapse if not repaired. Rose’s cabin, the guesthouse, is somewhat sturdier, though it’s slowly weakening too. Ontario Parks has taken a hands-off approach, with a sign advising visitors that the site is unmaintained and to enter at their own risk.

Each year, a group from Lakehead University makes the trip by canoe to visit the cabins. They’re always deeply moved by Beckwith’s work and legacy.

I won’t go much deeper into Beckwith’s story here, in part because his grandson Jim Hyder produced an excellent documentary in 2020 called In Search of Wendell Beckwith. I’ll include a link at the end of this story. It’s worth watching for the archival photos, the recordings of Beckwith himself, and the interviews with people who knew him. The film gives a rich and thoughtful look at one of Northwestern Ontario’s most fascinating stories.

There were so many parts of Beckwith’s life that stood out to me. His story made me realize that most so-called hermits, at least the ones people tend to write about, were not entirely alone. Many valued a sense of community, despite its unconventional appearance. What they often seemed to value was a mix of self-reliance, quiet reflection, and a deeper connection to the natural world.

Beckwith, and the others we’ll discuss today, went into nature and found a clarity of mind, body, and spirit that seems possible only in the wild. They learned to observe the world around them and used those observations to make sense of their place in Canada and shape their plans for the future.

They valued a slower pace of life. Not leisurely or idle, but steady. It was busy and often hard work, just without the pressure of the rat race or the pull of modern capitalist ventures.

What I’ve come to appreciate, and what I hope to convey, is that many of us find deep pride and meaning in making things of our own. Whether it’s a shelter, a tool, a piece of art, or anything else crafted with care, there’s something powerful about leaving a mark that reflects our effort and ability.

In every story I’ve looked at, it’s clear that people who find this kind of clarity in nature often become dedicated stewards of the land. They take that responsibility seriously and do what they can to protect it for future generations.

Story 1 - Jimmy McOuat and White Otter Castle

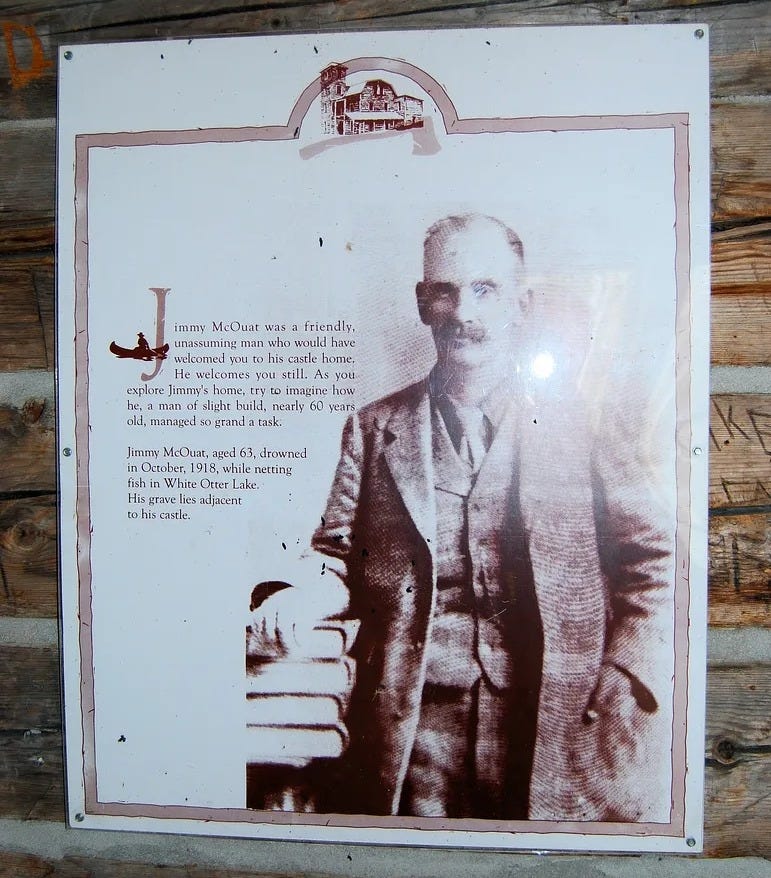

Our first story is about one of the more well-known hermits in Canadian history. His name was James Alexander McOuat, but most people knew him as Jimmy. Jimmy had something to prove—to himself, to the world, and maybe most of all to the person who told him as a boy that he’d never amount to anything.

Most versions of Jimmy’s life (and the castle he built deep in the remote wilderness of Northern Ontario) focus on that one driving idea: that he was determined to prove them wrong. According to the story, someone once told him he’d never do any good and would die in a shack, and the castle was his answer to that.

But I want to suggest, right from the start, that there’s more to this story. A lot more. Much of it, we’ll never fully know.

We can’t ask Jimmy himself. And, as is often the case with history, we’re left piecing things together from stories, recollections, and even Jimmy’s own words, which can be both helpful and a little tricky. That’s because it’s not always clear how reliable a narrator Jimmy was. Sometimes, it’s hard to tell whether he was telling the absolute truth, shaping a story to suit his needs, or just trying to entertain others.

It’s also possible that, like with many stories we repeat over time, Jimmy told it so often that he started to believe it himself. Of course, maybe he really was driven by just that one goal. But I think that sells him short.

Before we get too deep into what’s fact and what’s myth, I’d better tell you his story. Then you can decide for yourself.

Jimmy Alexander McOuat was born in 1855 into a family of Scottish immigrant stonemasons and grew up near Brownsburg, Quebec. He was the youngest of seven children. From a young age, Jimmy learned the value of hard work and resilience while gaining hands-on experience in construction alongside his family.

As a boy, he was once falsely accused of throwing a corn cob at a bad-tempered schoolmaster. According to Jimmy, it was actually a classmate who had thrown it. But the old man, having been struck, pointed the finger at Jimmy and scolded him with a bitter prediction: “You’ll never do no good. You’ll die in a shack.”

After finishing school (and with no further corn cob incidents that we know of), Jimmy began making a life for himself as a single farmer in his community. At the time, Canada’s western and northern frontiers were being opened up, and settlers were being encouraged to head out and establish homesteads.

In 1886, at age 31, Jimmy realized that as the youngest in his family, he likely wouldn’t inherit any land. He figured his best shot at owning land of his own was to head to the end of the rail line. So he boarded the Transcontinental Railway and made his way to Rainy River in northwestern Ontario.

By all accounts, Jimmy did well for himself in Rainy River. He quickly established a home, cultivated his land, expanded his farm operations, and prospered financially. He was small in stature, but he made up for it with grit and determination.

About a year after arriving, though, the loneliness started to catch up with him. He was far from family and still living alone without a family of his own. Too busy to go courting himself, he turned to a neighbour and friend and asked for help finding a wife.

Jimmy even wrote down some instructions to guide the search. His short list included

A young woman under 30

Someone unafraid of hard work

Willing to live in the remote wilderness

Any hair colour except fiery red

As for what Jimmy offered in return, he simply stated, “I’m not necessarily a rich or learned man, but I am honest and loyal.”

His neighbour turned out to be a pretty good matchmaker. A woman named Jane Gibson from Clifford, Ontario, agreed to marry Jimmy, but only on the condition that he come meet her family first.

Stubbornly, Jimmy refused to leave his homestead. We don’t know the full story of why he didn’t follow through, but because of that, the marriage never happened, and Jane moved on. After that, it seems Jimmy gave up on finding a bride.

By 1898, Jimmy’s farm was still going strong. He worked hard and even served on the local school board for a time. Friends described him as a good conversationalist who enjoyed company, even though he lived in a fairly remote part of Rainy River.

Despite his success, Jimmy, like many others at the time, was drawn in by the gold rush boom that hit near the end of the 1800s. When he heard about gold being discovered in northwestern Ontario, he decided to shift gears. He set his sights on mining, hoping to strike it rich.

In 1899, during the height of the gold rush, Jimmy sold his farm and invested everything he had in a mining venture on Upper Manitou Lake. It was a risky move, but Jimmy had taken chances before. His gut had led him west to Rainy River, and that had worked out. He was confident that this new adventure would also be successful.

Unfortunately, this is where Jimmy’s luck ran out. Within a year or two, the mining venture collapsed. He lost all his money and had already sold off his land. By 1900, he was nearly penniless.

Facing ruin, Jimmy turned to the one thing he still had: his skills as a woodsman and trapper. He began making a living by trapping fur-bearing animals in the Canadian wilderness.

For one reason or another, Jimmy never returned to farming. Instead, he followed wild game further west and north, which eventually brought him to White Otter Lake in 1903. This lake sits about 35 kilometres south of the town of Ignace, Ontario. On the north shore, far from civilization, Jimmy chose a site for his new homestead.

There, he built a simple one-room trapper’s cabin and survived his first year by fishing, hunting, and planting a small vegetable garden. He also made periodic trips to the nearest towns for supplies. Getting to Ignace meant canoeing the full 35 kilometres, which could take over a day in good weather and require no fewer than 15 portages along the way.

By the following year, the railway had pushed even farther west, and many settlers were heading into the prairies, lured by the promise of cheap land. But Jimmy was content to stay put on the shores of White Otter Lake.

According to local folklore, this is when that bitter old prophecy resurfaced in his mind—the one that claimed he’d never do any good and would die in a shack.

Having lost everything and now living in what was, quite literally, a shack, Jimmy set out to prove that prediction wrong.

As he entered middle age, he became obsessed with building something no one could ever call a shack. Over the next dozen years, he worked alone to construct a multi-story log home that left visitors stunned.

He chose massive Norway pine trees from the surrounding forest as his building material. Using only hand tools, he felled over 100 tall pines, each about 30 to 40 metres (just over 100 feet) long and roughly 50 centimetres (20 inches) in diameter. Then, without horses or machines to help him, he built a homemade winch and used block-and-tackle pulleys to drag the heavy logs from the forest to his building site near the lake.

Many of the logs weighed between 730 to 900 kilograms (1,600 and 2,000 pounds)!

It’s hard to believe a single man could handle such enormous timbers, but somehow Jimmy managed it through ingenuity and sheer will.

Once the logs were at the site, he shaped each one with an axe and a saw. He hewed the logs square on three sides for a tighter fit and carved dovetail notches at the corners so they would lock together securely. This was a far more advanced method than the simple notches used in basic cabins back then.

As the walls rose, Jimmy built wooden platforms and scaffolding. He used his block-and-tackle system to hoist the heavy beams, lifting them into place one by one. Witnesses later marvelled at the precision of his work, noting how perfectly the corners fit together. The structure wasn’t just solid; it was impressively level and plumb.

While building the castle, Jimmy still made time to take care of himself. He baked bread, chopped firewood, grew vegetables, and fished for lake trout to get through the seasons. He purchased supplies he couldn’t find in nature, such as flour, sugar, and oatmeal, with money earned from trapping and working as a summer watchman at nearby logging camps.

As a lumberjack, architect, and carpenter all rolled into one, Jimmy was resourceful. Since he had to haul in metal hardware from town, he cut wooden pegs and sparingly used nails. Between the logs, he packed chinking, a lime-and-sand mortar used to seal out the wind.

For the roof, he built a steep hip-style structure with four sides sloping up to a ridge at the top. Lacking cedar shakes or shingles on site, he covered the roof with tar paper for waterproofing. He had to transport items such as nails, windows, hinges, and roofing paper from town to White Otter Lake by canoe.

While Jimmy preferred to work alone, there are reports that he occasionally hired help for supply runs. Still, it’s said that he personally carried all 26 glass windows on his back through the portages, hauling them in bit by bit. He set each one into a store-bought wooden frame, which he also would have carried in. To this day, people are surprised he managed to do it all without breaking a single pane.

Between his construction efforts, Jimmy still made time to connect with people he’d come to know during his trips into town. He kept up friendships and regularly visited friends in Fort Frances and on the far side of White Otter Lake. One family he stayed close with, the Pedersens, welcomed him every Christmas during his years in northwestern Ontario. Their children remembered him fondly. They said he was kind, made them laugh, and always had candy ready when they visited his castle.

It’s clear by now that the story of one of Canada’s most famous hermits isn’t really a story of complete solitude. Jimmy was well known in the area, and many people liked and admired him. He was thoughtful and compassionate. On one occasion, he travelled many kilometres to deliver blankets and supplies to friends who had lost their home in a fire. People remembered his genuine smile.

And Jimmy also struck up a friendship with a visiting reporter known locally as Mr. Hudson. During Mr. Hudson’s summer visits, Jimmy would serve him chilled lemonade and walk him around the property. The reporter later wrote about this small, unassuming man living in the middle of nowhere, whose sharp eyes would sparkle and tanned face would beam as he showed off his castle, his flower beds, and whatever bit of nature he was excited about that day, including, at one point, a nearby beaver dam that stood over six feet tall.

For the most part, though, Jimmy preferred to interact with people on his own terms and be left in peace. He enjoyed long stretches of solitude, often watching birds and wildlife from his perch atop the four-story tower. From up there, he had a clear view of the land and of anyone approaching, whether welcome or not.

Jimmy was friendly and had friends, but he didn’t like people dropping in just to gawk or interrupt his work. As word spread about the man building a mansion by himself in the middle of nowhere, more and more curious visitors began to show up. He found it increasingly annoying.

What made it worse was that civilization was starting to creep closer. The longer Jimmy lived in nature, the more he tried to live in balance with it. He aimed to minimize his footprint, taking only what he needed to survive. But with each new visitor, he risked losing the quiet and wildness that made the place feel sacred to him.

A logging company moved into the area in 1912, seriously disrupting Jimmy's solitude. They built camps along the shoreline, opened up the forest, and laid down temporary roads to move timber out. He deeply resented the intrusion.

But he also saw an opportunity. Those same supply roads made it easier for him to haul in the last of the materials he needed to finish building the castle.

The loggers didn’t just disrupt the peace and quiet by clearing a vital part of the forest around the castle. They also put Jimmy’s homestead at risk when they built a dam that raised the water level. His small beach disappeared, and part of the water crept up over the base of the castle, threatening its foundation.

However, Jimmy outlasted the loggers, and by 1914, the walls were finished, and the roof and four-story tower were complete.

Let’s pause on that for a second. The tower stood at a height of four stories. Massive logs weighing over 1,600 pounds were used in its construction. And he did it by himself.

He was 59 years old.

Most of the work was complete, but he kept adding small finishing touches over the next year, celebrating his 60th birthday in the home he had built with his own hands.

In the span of about 12 years, Jimmy had built something no one would ever mistake for a shack. It was, without question, a mansion. But because of its remote location, with no other buildings for miles, locals embraced the name Jimmy used for it. They called it simply “the castle.”

One of the Pedersen children later recalled asking Jimmy why he had made up so many beds in the castle when he lived there alone. He told them, “One day, when I’m married and have a big family, there will be room for them all.”

Grace Pedersen, though, was never quite sure if that was a sincere hope or just a story Jimmy told to amuse the kids. Perhaps Jimmy told the story to avoid further questions.

There are all kinds of theories about why Jimmy chose a life of selective solitude. One possibility I haven’t seen mentioned, but that I couldn’t help thinking about, is that maybe it was a trauma response. After losing everything in the failed gold mining venture, maybe this life was a way to cope. People do all sorts of seemingly strange or inexplicable things when they hit rock bottom.

Maybe this was how Jimmy kept distance between himself and a society always chasing the next big boom, the same kind of thinking that had once ruined him. Maybe nature was simply the one place that felt truly healing and nourishing to his spirit, in ways he never put into words.

Regardless of his motivations, Jimmy focused on overcoming a final challenge once the castle was complete. But this time, it wasn’t something he could overcome through sheer will or determination.

White Otter Lake was Crown land, which in Canada means it was owned by the government. To legally claim his homestead, Jimmy needed to apply for a land patent. So, in 1915, he hired a surveyor from Kenora to conduct a formal survey and submitted his application.

Unfortunately, the Ontario government rejected it. For the next few years, Jimmy paddled back and forth to Ignace to use the post office and send letters appealing the decision. Although the province had clearly denied his claim and reminded him that his cabin was built within a timber limit leased to a logging company, Jimmy held on to one detail that gave him hope: they had kept his deposit and issued a receipt. To him, that meant the door wasn’t fully closed.

During all of this, in a remarkable show of compassion, Jimmy wrote to the Ontario government near the end of World War I and offered his castle as a convalescent home for wounded soldiers. He believed that a peaceful, remote place like White Otter Lake could help them recover from the physical and emotional toll of war. It’s not hard to imagine that he might have been right.

But the government declined his offer.

In 1918, Jimmy tried once more, this time with more urgency, to secure legal title to the land around his beloved castle. Again, the province denied his application.

As winter settled in that year, James prepared as usual, stocking up on supplies and fitting in some last-minute fishing before the lake froze over. But when James didn’t show up for Christmas dinner at the Pedersens’, as he always had, the locals began to worry. Locals had already noticed he hadn’t made as many supply runs that fall, at least not as often as in past years.

When spring came and the ice melted, James still hadn’t appeared in Ignace. In June of 1919, people began searching for him.

Not knowing where else to turn, the Pedersens made the trip across White Otter Lake by boat. There, they were met by forest ranger T.C. Campbell, who delivered the news: James had been found. He had drowned.

The report in the Thunder Bay Times was especially grim. It read:

“The body of Jimmy McQuat, the hermit of White Otter Lake, who has been missing since last October, was found on June 27th by T.C. Campbell, a fire ranger. The head and arms were gone, but the body was identified, and the mystery of his disappearance was solved. He had fallen into the water near his home while working on his nets and, becoming entangled with them, was drowned, although he was said to be a good swimmer...

…In addition to his castle, he also built a tomb for himself near his home, where it was his wish to be buried. He feared the curse might be fulfilled and his last resting place left unmarked. The wishes of the strange old man have been complied with.”

There’s something romantic, admirable, and undeniably sad about Jimmy’s story. I tried to include as many details as I could to show that he was far more than just a hermit living alone in the woods.

Yes, he spent a lot of time by himself—building his castle, sustaining his lifestyle, and enjoying nature—but he was also a loyal friend, a kind soul, and a careful observer of the world around him.

There are myths and rumours that Jimmy’s spirit now haunts the grounds of the castle, which today sits mostly abandoned and covered in graffiti. Whether you believe in ghosts or not, that part is up to you. You can dig into that side of the story if it interests you.

But I will say this: ghost stories often involve a soul stuck between worlds because something was left unfinished. In Jimmy’s case, it seems to me that he finished what he set out to do.

He built his castle.

He lived on his own terms.

He did do good.

And he did not die in a shack.

While the Ontario government never granted Jimmy permission to build or live in his castle on White Otter Lake, they have, in the years since his passing, officially recognized it as a historic site. And, to their credit, there have been efforts to make sure his story is remembered.

Much of that credit also goes to a group of local volunteers called the Friends of White Otter Castle Inc. They’re local history enthusiasts who, every so often, return to the castle to clean, repair, and help preserve it.

The castle still stands where Jimmy first built it, and the surrounding area remains largely untouched. In 1989, the creation of Turtle River–White Otter Lake Provincial Park helped protect the site. Logging efforts that once threatened the forest were eventually abandoned, as nature itself pushed back and reclaimed the space. The tall pines still stand, along with everything they shelter.

To the government’s lasting credit, they honoured Jimmy’s final wish. He had written that, if he died, he wanted to be buried on the land where he built his castle. Today, his grave sits beside the home he poured his life into. The quiet marker serves as a reminder to anyone passing by that James "Jimmy" McOuat was more than just a local legend.

He was a real person who lived and died here.

And he’s the only one who will ever truly know why he chose the life he did in the final decades of his life, most of which he spent building something only he could imagine.

Story 2 - Gilean Douglas and her life in the BC Wilderness

The next story I want to share is about someone who also retreated into nature, found a remote place away from modern society, and drew deep inspiration from it to create great literature.

Where Jimmy McOuat spent his hermit years building a castle, Gilean Douglas spent hers building a body of work that would become a key part of Canadian literary history. Her writing—especially her poetry—captured the natural world with a depth and clarity that placed her among the most important Canadian women poets of the mid-to-late 1900s.

Gillian Douglas was born on February 1st, 1900, in Toronto, Ontario. She was the only child of William Murray Douglas, a prominent lawyer who became a King’s Counsel, and his wife, Eleanor Constance Coldham, better known as Nellie.

Gillean’s childhood was one of privilege. Her father was wealthy and well-connected. She could read by the age of five, and by seven, she was already contributing to a children’s column in the Toronto News. She received a private education and often travelled with her parents to England, Europe, and across North America.

But despite her urban, high-society upbringing, Gillean always felt a strong pull toward nature. Even as a child, she loved being outdoors. It was a passion that hinted at the independent, nature-focused path she would eventually choose.

Tragedy struck early in Gillian’s life. Her mother died suddenly when she was just seven years old. Less than a decade later, her father died of a heart attack. She was only sixteen.

Orphaned in 1916, Gillian inherited her family’s fortune but also a profound sense of being on her own. In her late teens, she made a symbolic break from her old life by changing the spelling of her name from Gillian to Gilean. Around this time, during the final years of World War I, she left behind the comforts of wealth and volunteered for farm service as part of the war effort.

Working on rural farms gave her her first real taste of physical labour and living close to the land. One of her biographers noted, “This is when Gilean really started taking an interest in the natural world.”

In 1919, at the age of 19, she returned to Toronto to try and make her own way in the world. But city life didn’t suit her. The pollution aggravated a thyroid condition she already struggled with. Still, she pressed on and started a career in journalism at a time when Canadian women still couldn’t vote federally and were largely expected to become teachers or nurses.

As we’ll explore, Gilean was never one to take a predetermined path. She became a newspaper reporter.

She managed to land a job with the Toronto News, working as a reporter and editor of the children’s page. She earned about twenty-five dollars a week. That may not seem like much now, but for a young woman in the 1910s, it was a bold move.

World War I had sparked national conversations about gender inequality and women’s economic independence, and Gilean was paying attention. She was determined to succeed in a male-dominated field. After everything she’d already overcome, she believed she was up to the challenge.

In the early 1920s, while Gilean was developing some feminist leanings and ideals, her personal life took a more traditional turn. She married Cecil “Slim” Rhodes on February 17, 1922.

At first, Slim seemed like a suitable match for Gilean’s determined and unconventional spirit. He even agreed to take her last name, becoming Cecil Rhodes Douglas (an unusual choice at a time when women were still expected to take their husband’s name).

Gilean, who was affectionately nicknamed “Bobs” at the time, set off with Slim on a honeymoon road trip across the American Midwest. They travelled from camp to camp, staying in tourist cabins and living a kind of rugged adventure. Along the way, Gilean discovered a new passion: photography. She took pictures of the places they visited, documenting their journey.

She cherished the freedom of travel and the experience of capturing it through her camera lens. But the marriage didn’t last. In 1925, after just three years, Slim abruptly deserted her. Left emotionally and geographically stranded, Gilean returned to Toronto.

Newly single, she threw herself back into journalism. She took on an investigative project that sent her around the Great Lakes to report on conditions aboard big freight ships. For two years in the mid-1920s, she travelled across Northern Ontario, combining reporting with wilderness recreation.

When she wasn’t interviewing sailors or inspecting freighters, she was camping, canoeing, hunting, or skiing with friends in the northern woods. This blend of work and outdoor life suited her independent spirit. It helped her sharpen her wilderness skills and build confidence in navigating rugged terrain.

By this point in her life, it was clear that Gilean was searching for freedom and meaning. Her restless spirit kept her moving and exploring across Canada for both work and personal adventure.

In 1928, she set her sights beyond the country’s borders and moved to Reno, Nevada. While there, she kept writing and became involved with the YWCA, an organization that supported young working women.

In July 1929, Gilean decided to give marriage another try, this time to Charles Norman Haldenby.

But this second marriage ended even faster than her first. According to some reports, her first husband, Slim, showed up unannounced and caused a scene. Spooked by the drama, Haldenby abandoned ship on their wedding night and disappeared from her life just as quickly as he’d entered it.

Undeterred, Gilean gave marriage one more try. In 1930, she married a chemical engineer named Eric Altherr. Slim didn’t crash this one, and the ceremony went ahead without incident.

For a few years, Gilean balanced married life with her writing career. Throughout the 1930s, she produced a steady stream of poetry and continued working as a journalist. Much of her writing from this period explores themes of love and heartbreak, drawing on her own turbulent experiences with relationships.

In 1934, tragedy found Gilean once again, this time in the form of a miscarriage. As you can imagine, it would have been heartbreaking and devastating.

My partner and I had a miscarriage 18 years ago, a few years before the birth of our only daughter. It was easily one of the worst experiences I’ve ever had. Fortunately, we went through it at a time when it wasn’t taboo to talk about miscarriages or the emotional impact it can have on people and relationships. Without the space to talk, process, and feel supported and understood, I honestly don’t know how people get through it.

It demonstrates how resilient Gilean was in the face of such agony.

A few years later, Gilean’s third marriage ended. She and Eric had grown apart and had both become involved with other people. From what I've read, there's no mention of the miscarriage as a factor in their relationship breakdown. Maybe it played a role. Maybe it didn’t. Sometimes, people simply grow apart.

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 brought increased financial strain for single, independent writers like Gilean. Rather than stay in Toronto or pursue conventional work, she made a bold choice.

She chose solitude in nature over society’s expectations.

That same year, she moved to a remote cabin in the coastal wilderness of British Columbia, seeking a simpler, more self-reliant life. The decision would define the next chapter of her story. In many ways, it was a return to something familiar, a connection to the natural world that had brought her comfort since childhood.

At 39 years old, she embraced the chance to start fresh on the West Coast, settling first in a cabin along the Coquihalla River in the Cascade Mountains.

The setting, with its steep, forested valleys and rushing river, stood in stark contrast to the noise and pace of Toronto or the dry deserts of Nevada. Here, Gilean lived in near-complete solitude, embracing the daily work of wilderness living. She chopped wood, hauled water, and grew or foraged much of her own food.

She continued to write articles and poems, sending them off to publishers from her mountain outposts. The work brought in a modest income.

But writing about her life as a woman alone in the woods came with challenges. Many editors, and readers, at the time couldn’t quite believe that a “lady” could also be a rugged, independent backwoods homesteader.

After some time in her cabin, Gilean sought an even more remote sanctuary. She moved to an abandoned miner’s shack on the Teal River, near the town of Duncan on Vancouver Island. This placed her deep within the wild terrain of the West Coast, surrounded by dense rainforest and rushing rivers.

It was in that Teal River cabin that she later said she found her greatest sense of peace and tranquillity.

Writing about her arrival, she recalled:

“It was the great moment of my life when I waded the Teal River with my pack board on my back and stood at last on my own ground. I can never describe the feeling that surged up inside me then… I felt kinship in everything around me, and the long city years of noise and faces were just fading photographs.”

Gilean described how freeing, and at times frightening, it felt to be alone in untouched wilderness, surrounded by towering trees and the sounds of the forest.

As Andrea Lebowitz, a professor of English and Women’s Studies, once wrote,

“An initial year of coming to terms with isolation and solitude changed intimidation into release, and she [Douglas] settled into the pattern that would shape the rest of her life: working the land for survival, observing and immersing herself into the natural world, and writing.”

At the Teal River cabin, Gilean lived a fully self-sufficient life. The old shack had no electricity or modern conveniences, so she relied on wood fires for heat, lanterns for light, and water drawn straight from the river.

She planted and tended to a large vegetable garden, which provided most of her food. The fertile riverside soil was ideal for growing potatoes, corn, berries, and a variety of greens.

What she couldn’t grow, she foraged or caught. She fished in the river and gathered wild berries, nuts, and edible plants from the forest. In one of her books, she listed the range of wild foods she came to know and use:

“Salal, salmonberries, thimbleberries… gooseberries, wild cherries, blue currants… There were hazel catkins to eat, wild dandelion root coffee… Labrador tea, miner’s lettuce, sage… mushrooms, strawberry and plantain.”

Gilean also hunted or trapped small game occasionally and kept a rifle for protection, but she mostly coexisted peacefully with the wildlife around her. She even wrote fondly of a resident cougar she nicknamed “Grandpa Cougar,” who shared the territory near her cabin—a sign of the deep respect she developed for animals and the land.

Solitude in a place like this required creativity and determination. Like Jimmy McQuatt, Gilean didn’t want to become a spectacle or to be interrupted by curious visitors.

To discourage drop-ins, she rigged up a hand-operated pulley cable car across the Teal River. This simple aerial tramway allowed her to cross the river by pulling herself in a suspended basket or platform. It also meant that anyone hoping to visit would have a hard time getting in, unless she invited them and sent the cable car across.

And she rarely did. Few people were ever welcomed to stay at her “camp.” Gilean fiercely guarded the quiet and tranquillity of her sanctuary.

The result was a life of near-complete isolation, broken only by occasional visits from a few trusted friends. Surrounded by forest and river, Gilean found a daily rhythm that brought her contentment.

Years later, a summary of her work noted that River for My Sidewalk, her first memoir, “describes the author’s way of life in the wilderness of British Columbia, the beauty of the natural world around [her], and the joys of solitude.”

Like Wendell Beckwith, she also developed a scientific interest in her surroundings. In the early 1940s, she began closely observing wildflowers, trees, and animals near her cabin and tracking their behaviours and seasonal patterns. Over time, she folded those observations into her writing, blending natural history with lyrical reflection.

In many ways, her solitude turned her into both a writer and an amateur naturalist. She was living “off the grid” long before that phrase existed. And she was thinking like an environmentalist before the term had become mainstream. Gilean believed in respecting the land and minimizing her impact. Principles that would later echo through the broader environmental movement.

Even while living as a hermit writer, she stayed productive and connected to the outside world through her work. She kept writing poems, essays, and articles, either by hand or on her portable typewriter—one of her most prized possessions, now preserved at the Cortes Island Museum and Archives.

(Why at the Cortes Island Museum and Archives? Don’t worry, you haven’t missed anything; we’ll get to that shortly.)

First, let me tell you that as romantic as the appeal of living alone in the vast BC wilderness might seem, make no mistake, this lifestyle also came with serious hardship, and Gilean endured more than her share.

Winters were harsh. Gale-force winds tore through her drafty cabin, and snow didn’t just settle gently on the ground; it often fell in heavy, impassable drifts. When storms swelled the river, she could go days without being able to cross for supplies.

She lived with very little money. Aside from modest income from her writing, she sometimes traded or sold excess produce from her garden to buy essentials. Yet somehow, she thrived, and from what I can tell, she never wrote about her bad experiences. Years later, she would describe the roughly seven years she spent in that cabin as the most joyful time of her life.

Sadly, that chapter ended in disaster. A fire swept through her cabin in 1947, destroying it completely. The blaze destroyed nearly everything—manuscripts, journals, and the home she had built with care. Gilean was left with nothing but the clothes on her back and the experiences she carried with her. It was a devastating loss, not just of property, but of the sanctuary she had created.

She was 47 years old, and once again, she had to start over.

Homeless but undeterred, Gilean didn’t return to city life this time. Instead, she stayed for a while on Keats Island, near Vancouver. There, she regrouped and made new plans.

During that time, fate brought her a final chance at companionship. She met a man named Philip Major, who was visiting the area. They connected over a shared love of the coastal lifestyle.

On June 1, 1949, Gilean married Philip in her fourth and final marriage. That same year, the two purchased a 138-acre waterfront property at Whaletown, on Cortes Island, one of the northern Gulf Islands off the coast of British Columbia.

Little did Philip know, he was helping Gilean secure her next and final sanctuary. The land they bought would be her home for the rest of her life.

In the early 1950s, Gilean Douglas settled into her new home on Cortes Island. Here, atop a bluff overlooking the sea, Gilean finally put down lasting roots. She named the property Channel Rock, after a prominent rock outcrop along the shoreline.

Channel Rock was extremely secluded. There was no road access. You could only reach it by boat or by hiking through the forest. There was no electricity and no plumbing. For Gilean, it was perfect. The isolation and beauty of the place made it an ideal sanctuary where she could write, garden, and live on her own terms.

Life on Cortes Island in the 1950s still had a pioneer feel to it. Gilean and Philip built a small cottage at Channel Rock, which became their home. It was a simple place, warmed by a woodstove and lit by kerosene lamps. They dug a root cellar for storing vegetables, which was essential for year-round living. (Local historians note that “Gilean Douglas’ root cellar at Channel Rock” became a well-known example of early homesteading on the island.)

Gilean established another large garden, growing enough produce to sustain herself and to sell or trade the extras. She planted fruit trees, kept hens for eggs, and, of course, cultivated flowers. Her beloved peonies thrived in the garden. The island's heritage garden project later received some of these peonies.

With the sea at her doorstep, she could fish or collect shellfish. Deer and other wildlife wandered freely across the property.

Gilean embraced this abundance, living largely off the land. Neighbours recalled how she would sometimes paddle her rowboat to nearby communities to trade fresh vegetables for supplies. In essence, she had recreated the self-reliant lifestyle she once lived on the Teal River. But this time, she had the benefit of experience and a partner to share the work.

In those pre-Internet days, she mailed her manuscripts to editors in distant cities. But whenever she wrote about her time alone on the Teal River, she often faced rejection. Editors still doubted that a woman could truly live alone in the wilderness and write about it convincingly.

Gilean came to understand that this bias wasn’t going away anytime soon. So she made a bold decision: she adopted a male pen name, “Grant Madison,” and began submitting her wilderness writing under that identity.

It worked. Her work received more serious attention almost immediately, enabling her to finally publish her first book.

In 1953, she released River for My Sidewalk, a memoir of her years by the Teal River, under the name Grant Madison. The book, now considered her best-known work, tells the story of her solitary adventures and observations of nature in a series of short essays and anecdotes. Readers assumed Grant Madison was a man, and she maintained the illusion for decades, only stepping out from behind the pseudonym in a 1983 interview published in the Vancouver Sun.

Gilean also found ways to contribute to the women’s rights and equality movements. She joined the Women’s Institute in Whaletown and the Women’s Auxiliary of the Anglican Church and even helped establish a local community club. Through the Women’s Institute, she advocated for education and improvement projects that supported women in the area.

But this growing public role didn’t sit well with Philip. He may have expected a more conventional wife or felt sidelined by her independence. By the early 1950s, only a few years after moving to Cortes, the couple separated and eventually divorced. Philip left the island. Gilean stayed. She wasn’t about to give up the sanctuary she’d worked so hard to create.

After the divorce, Gilean Douglas lived alone at Channel Rock for over four decades, from the 1950s until her death in 1993. She truly fulfilled her vision of an independent life in nature.

Though she lived in near-complete solitude day to day, Gilean was not a recluse. She became a respected figure in the Cortes Island community and beyond.

In 1961, she began writing a weekly nature column called Nature Rambles for the Victoria Daily Colonist, one of BC’s major newspapers. Amazingly, she kept it going for 31 years until 1992. In each column, she shared her observations about seasonal changes, wildlife behaviours, and conservation issues. Her writing brought a slice of Cortes Island wilderness into homes across the province.

The consistency and longevity of Nature Rambles made Gilean one of BC’s longest-running columnists.

She also put her outdoor skills to practical use. As an official weather observer for Environment Canada, she sent daily weather data from her oceanside perch to meteorological authorities. The role gave her a small income and a scientific purpose.

In addition, she volunteered in local Search and Rescue efforts, helping with coastal emergencies when needed. Even in her 50s and 60s, she didn’t shy away from rugged responsibilities. Her cottage at Channel Rock became known as a place equipped with a radio and first aid, where she could help coordinate or assist in emergencies.

And then in the 1970s, Gilean entered local politics. From 1973 to 1978, she served on the regional governing board, the Comox-Strathcona Regional District’s Advisory Planning Commission and Environment Committee. She worked on land use planning, pollution control, and the protection of wetlands and salmon habitats.

It’s striking that someone who prized solitude as deeply as Gilean also gave so much to her community. But it speaks to who she was: someone who believed in protecting the nature that gave her sanctuary, not just for herself, but for generations to come.

Over the decades, Gilean wrote and published a remarkable body of work.

She began with River for My Sidewalk (1953), then followed it with a steady stream of poetry collections. Much of her poetry celebrated nature and solitude, often using vivid imagery drawn from the coast and mountains. Some poems were so evocative they were set to music. Companies like G. Schirmer arranged and published several poems as songs in the mid-20th century. Public performances even featured choral works based on her poetry. Through these musical interpretations, her love of nature reached ears as well as eyes.

Alongside poetry, Gilean also wrote non-fiction and memoirs about her wilderness life. She published two more autobiographical books: Silence Is My Homeland: Life on Teal River (1978) and The Protected Place (1979).

Silence Is My Homeland returned to her years on the Teal River, reflecting on the lessons she learned from solitude. The Protected Place focused on her life at Channel Rock, describing the rhythm of the seasons and her philosophy of living in harmony with the land.

Even the title, The Protected Place, suggests how she saw her solitude: not as isolation, but as refuge. As she once wrote, “I have spoken many times of ‘my land’ and ‘my property,’ but how foolish it would be of me to believe that I possessed something which cannot be possessed.”

Gilean understood that the wilderness wasn’t something she owned. If anything, the land owned her. She was its caretaker, and it offered her spiritual shelter in return. That reverent, humble view of nature runs through everything she wrote.

A 1984 biography noted, “Her work has appeared in numerous periodicals both here and abroad,” citing at least 144 different publications. Her byline (or her pseudonym) showed up in everything from Chatelaine and the Ottawa Citizen to the Saturday Evening Post, Audubon Magazine, and The New York Times.

Such a wide range of publications speaks to the lasting appeal of her writing. Her firsthand accounts of nature's challenges and beauty captivated readers. She also drew them in with her clear, honest, and thoughtful voice.

As the decades passed, Gilean became something of a legend on Cortes Island. Locals knew her as the kindly, fiercely independent older woman living alone at Channel Rock. She was often seen hiking the forest trails or rowing her boat along the shoreline well into her senior years.

She handled health challenges the same way she handled everything else: with quiet independence. Gilean had a lifelong thyroid condition that had troubled her since youth, but she consistently refused surgery or major medical intervention. Even in her nineties, she stuck to her self-sufficient ways.

By 1992, when she was 92 years old, her health began to deteriorate significantly.

Friends and advisors gently suggested she consider selling her beloved property and moving somewhere less remote for her final years. Gilean flatly refused. She would not give up her sanctuary. She also declined an old-age pension from the government, perhaps out of pride or simply a desire not to be beholden to anyone.

In the summer of 1993, she fell gravely ill and had to be airlifted from Cortes Island to a hospital in Campbell River. True to form, she recovered just enough to return home one last time.

On October 31, 1993, Gilean Douglas died in her cottage at Channel Rock at the age of 93. She passed away in the place she cherished, surrounded by a few close friends and neighbours who had become her island family.

When Gilean died, Canada lost a pioneering nature writer and an extraordinary woman. She had lived through nearly the entire 20th century, from 1900 to 1993, and witnessed enormous cultural change. But through it all, she stayed true to her own path.

In a time when most women were expected to follow a conventional domestic life, Gilean chose radical independence. She made solitude her sanctuary and found in wilderness the freedom, meaning, and spiritual home that society didn’t offer her.

Her writings, created over the span of eight decades, chronicle that journey. They reveal a woman who sought, in her own words, “to lose herself in the natural world” to find her true self.

And like the great nature writers who came before her, she discovered that immersion in the wild gave her both perspective and purpose.

Perhaps the most fitting way to end our look back at Gilean Douglas’s remarkable life is with a verse from one of her poems. It captures, in her own words, what she (and others like her) were seeking and ultimately came to understand during their time in the Canadian wilderness:

If we still praise tall mountains and the sky

It is because there is a need to know

that, in the darkly sanguine ebb and flow

With reason lashed upon the spar of why,

Here is serenity: men war and die,

Yet peace remains. The frail years come and go,

But here is calm and certainty that no

A mad mouth of greed can shame or terrify

("Nature Poets in Now," Prodigal 17).

Story 3 - Chief Robert Smallboy’s Alberta Camp Far From Modern Society

So far, we’ve explored how individuals have left the world they knew to live more secluded, self-sufficient lives while still relying on interdependence and maintaining connections with others on their own terms.

But what happens when an entire community chooses to step away from mainstream society? What happens when a group moves into nature to form a self-sustaining microcommunity, deeply connected to the land, and intentionally resistant to parts of the outside world?

To explore that idea, I want to tell you about Chief Robert Smallboy’s camp in Alberta. It began in the late 1960s and still exists today. It’s a fascinating case study of a small community that returned to a more traditional way of life. One that was thoughtful about which elements of modern society to bring in and which to leave behind, all while staying true to its core values and beliefs.

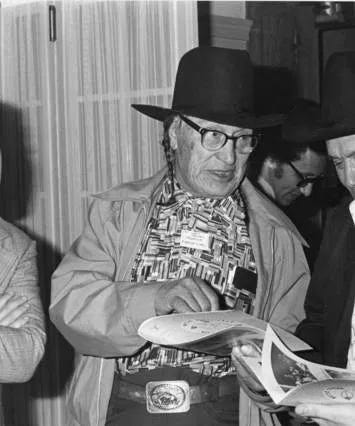

Robert “Bobtail” Smallboy was born on November 7, 1898, into a family with a rich Indigenous heritage. He was given the Cree names Keskayo (meaning “Bobtail”) and Apichitchu (meaning “Small Boy”) in honour of his maternal grandfather, a respected Cree chief also named Bobtail.

Smallboy’s lineage included many notable leaders. On his mother’s side, he was a descendant of Chief Big Bear (Mish-tahi Muskwa), a revered Cree leader from Saskatchewan, and Chief Bobtail (Alexis Piché), a Cree chief in Alberta. On his father’s side, he was the grandson of Chief Rocky Boy, also known as Stone Child, a Chippewa-Cree leader in Montana who helped establish the Rocky Boy Reservation in the United States.

This mixed Cree and Chippewa ancestry meant that Robert Smallboy grew up with a broad Indigenous perspective. As a child, he spent some years in Montana on the Rocky Boy Reservation, where he learned to speak Cree, but with a Chippewa accent.

By the time of World War I, the Smallboy family had returned to Canada. They camped on the Kootenay Plains. It was there that Robert first saw the area that would eventually become his future camp, far from the reserve and mainstream society. Eventually, the family settled on the Ermineskin Reserve, which is located in Hobbema, Alberta.

During that return to Canada, Robert’s siblings Maggie, Johnny, and Billy were present. He had already lost two siblings to pneumonia during the harsh winters, when the family survived on scraps tossed out by meat markets. His mother, Isabel, gave birth to 12 children in total. Only 8 survived infancy, and just 6 made it to adulthood.

In the early to mid-20th century, Robert Smallboy lived a fairly traditional life on the reserve. He became a skilled hunter, trapper, and farmer, well-known for his work ethic and deep knowledge of Cree traditions. In 1918, he married Louisa Headman at Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows Church in Hobbema.

During World War I and the years that followed, Indigenous people in Canada were required to declare which reserve they belonged to and could not leave without a written pass from an “Indian Agent” (a government representative enforcing colonial policy).

Smallboy remained on the Ermineskin Reserve with his mother while his father returned to Montana to determine the band’s political future there. These were turbulent times, both in Europe and at home. For Indigenous people, they brought even greater restrictions, disruptions, and challenging choices.

During World War I, there was a major labour shortage and a growing demand for farm workers. Many farmers had joined the war effort, and Canadian farms were expected to feed not just Canadians but also our allies overseas. Encouraged by his father, Robert Smallboy began working on farms during this time, learning how to apply his Indigenous knowledge to agriculture and farm management.

By the end of the war, Smallboy had become a successful farmer and showed he could adapt to the droughts and economic struggles that followed. He was a thoughtful observer, a good listener, and wise beyond his years. He also had a gift for foresight and planning. One technique that helped him survive difficult years was to hold back some of his seed supply rather than planting it all at once. This way, he avoided having to pay inflated prices for new seeds if the market shifted the following year.

During the early 1900s, traditional Sunday dances were banned by the Canadian government. As a result, Smallboy’s father had to return to Montana, where these cultural practices were still allowed, to participate in important ceremonies. But even that didn’t last. In July 1925, Montana also banned sun dances.

That summer, Smallboy accompanied his father, relatives, and other community members back to Montana to protest the ban. Together, they held a series of dances to reclaim what the U.S. government was trying to suppress.

This was one of many examples of government efforts, on both sides of the border, to erase Indigenous cultural and spiritual practices. Smallboy witnessed this erasure firsthand in his early life.

Between the First and Second World Wars, and for a time after, he refused to learn English. He made a point of doing as much as possible in traditional ways. He couldn’t understand why Indigenous people were expected to rely on white Indian Agents to make decisions about their land, their money, and their future.

By the 1950s, Robert Smallboy had become one of the most productive farmers in his community. His integrity, hard work, success in farming, and deep cultural knowledge earned him widespread respect among the Ermineskin Cree.

In 1959, following the guidance of his predecessor, Chief Dan Mindy, Smallboy was elected Chief of the Ermineskin Cree Nation—one of the four bands of Maskwacis.

He would later say that it was only after becoming chief that he became fully aware of the corruption happening behind the scenes. He was shocked and disheartened to discover the presence of bribes and dishonesty between elected Indigenous leaders and the Department of Indian Affairs.

He was determined not to become part of that system.

Despite early approaches with bribes, he promptly shut them down. He made it clear that he would never accept a system that allowed outsiders to impose programs and policies on Indigenous communities without consultation or consent.

Chief Smallboy strongly rejected the idea that a non-Indigenous government should control Indigenous affairs.

He tried to raise his concerns directly with the Head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The issues he wanted to discuss were urgent and deeply rooted. The reserves were overcrowded. Job opportunities were scarce. Families were breaking apart. Alcoholism and child neglect were rising. Too many Indigenous people were in jail. Too many children were failing in school. Disease was widespread.

He saw a loss of pride and dignity at the individual level. Collectively, Indigenous people had been stripped of their religion, their culture, and their social structures. Many were left feeling they had no meaning in their lives. Increasingly, he said, their only escape was suicide.

Smallboy travelled to Ottawa more than once to speak directly with Canadian government officials. He expressed deep concern for the well-being of his people, having witnessed firsthand the changes brought by the post-war era. These included increased oil and gas development on reserve lands, the decline of traditional subsistence lifestyles, and the ongoing trauma of the residential school system.

Each time, Smallboy warned that the future of his people was at risk. And each time, the government refused to act on his concerns, instead telling him to work within the existing policies of the Indian Act.

Desperate to be heard, Smallboy also reached out to high-ranking religious officials. He even went to Rome to plead his case to the Pope. Since many of the Maskwacis Cree were Catholic, he hoped the Church might listen where the government had not.

In Rome, he raised urgent issues: the need for more land, high unemployment, and the breakdown of family units. He warned that his people were experiencing a “great loss of pride, dignity, religion, and social order,” leaving many with no clear purpose or hope.

Despite his pleas, he felt they were ignored.

To fully understand what Smallboy was trying to address, it’s important to recognize the broader context: the legacy of residential schools, increasing urbanization, pressures to assimilate, substance abuse, and a range of social crises were all bearing down on his people.

Throughout the early 20th century, Indigenous children in Alberta were often taken from their families and forced to attend residential schools. In Hobbema, the Ermineskin Indian Residential School, run by Roman Catholic missionaries, operated from 1895 until 1975.

By the 1960s, many adults living at Ermineskin had been forced to attend these schools as children. There, they experienced cultural suppression, harsh discipline, and, in many cases, abuse. The legacy was devastating: broken family bonds, loss of language and cultural knowledge, and deep psychological trauma for survivors.

Although by the 1960s the residential school system was beginning to wind down, gradually replaced by day schools and limited local control, the damage had been done. Chief Smallboy viewed the “breaking down of family units” and children “performing poorly in school” as symptoms of this painful legacy.

In the post–World War II era, more Indigenous people in Alberta began migrating to cities in search of jobs, housing, and education. This shift was partly encouraged by government policies that saw the reserve system as outdated. But in urban centres, Indigenous people often faced blatant discrimination.

For example, Lillian Shirt, a First Nations single mother, was refused rental housing in Edmonton in the 1960s simply because of her identity. Many Indigenous families who moved to the city ended up living in poverty. Those who stayed on reserves faced overcrowding and limited economic opportunities unless they happened to live on land with oil. The new resource economy only benefited a select few individuals.

Another major issue was the federal policy of enfranchisement. Until 1960, Indigenous people could lose their legal status if they pursued higher education or served in the military. That policy ended the same year as status Indians were finally granted the unrestricted right to vote. But by 1968, there was still enormous pressure on Indigenous people to “assimilate” to become fully Canadian by abandoning traditional life.

This left many young people facing an identity crisis, torn between fitting into mainstream society and preserving their culture.

The 1960s were also a time when the social struggles in many First Nations communities became harder to ignore. Alcohol, introduced decades earlier, had become a common escape from pain and trauma, but it often led to cycles of addiction and violence. By the late 1960s, drugs were beginning to make their way onto some reserves as well.

Chief Smallboy spoke openly about the damage this was doing, which included rampant alcohol and drug use, neglect of children, and a growing loss of spiritual direction.

Ironically, the rapid influx of oil money to the Ermineskin Reserve during this period may have made things worse. With sudden wealth, some community members could afford more alcohol. But without strong cultural anchors, many fell into misuse and addiction. Smallboy believed that rising alcoholism, drug abuse, and suicide were all linked to trying to live a “modern” lifestyle on the reserve rather than following what he called “the Indian way.”

Modern developments, including television and oil wealth, were, in his view, eroding Cree language, spirituality, and family structure.

The knock-on effects of addiction were severe. Accidents related to drunk driving and other alcohol-related injuries were becoming more frequent. Although certain material conditions on the reserve had improved, the social issues had deteriorated.

By 1968, after nearly a decade as chief, Smallboy had become deeply disillusioned with life on the reserve and the influence of white settler culture on his people. That year, he made a dramatic decision.

He announced that, for the sake of the next generation, “for the future of our children and grandchildren,” he would leave the Ermineskin Reserve and return to traditional territory in the Rocky Mountains. The goal was to escape what he saw as a harmful modern environment and return to a way of life rooted in the natural world and guided by the teachings of his forefathers.

In effect, he resigned his official position as chief and became the leader of a new off-reserve community. It was not a decision made lightly. It meant moving entire families and giving up modern housing and services. But Smallboy believed it was the only way to live a “good, peaceful life,” far from the influences that were harming his people.

With support from several others, including Simon Omeasoo, Lazarus Roan, and Alex Shortneck, he organized the exodus that would become known as the founding of the Smallboy Camp.

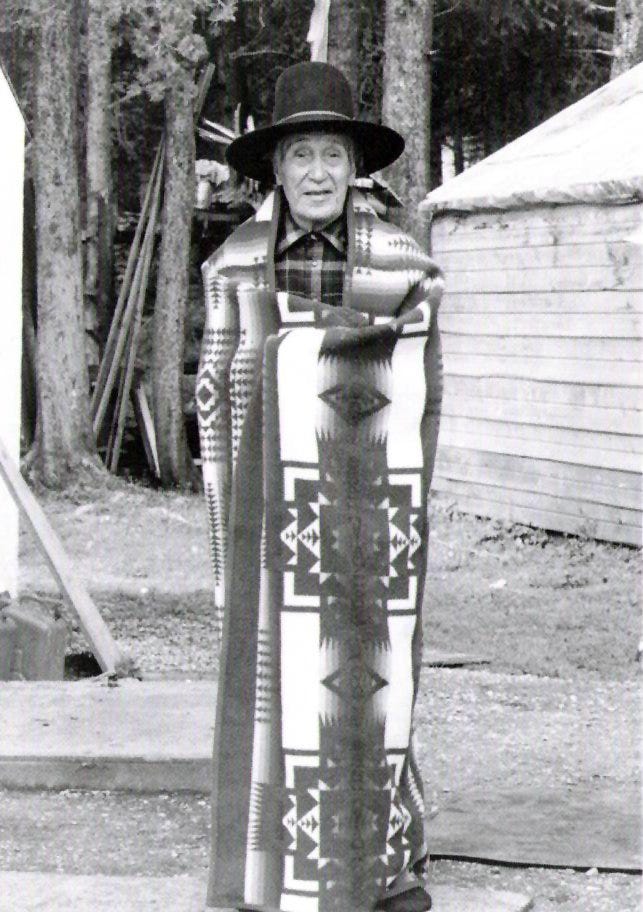

Following the announcement of his planned departure, Chief Smallboy and more than 100 followers left the Ermineskin Cree Nation Reserve and established a remote camp on the Kootenai Plains in west-central Alberta. That summer, about 125 to 140 people joined him. They packed up their tents and teepees and journeyed roughly three and a half hours west of Edmonton, settling near the Rocky Mountains, in the same area where Smallboy had camped with his family upon returning from Montana 50 years earlier.

The group pitched a large council teepee and about 20 smaller tents on an open plain north of Abraham Lake. From the beginning, Chief Smallboy set strict rules to preserve the camp’s purpose as a sanctuary. Alcohol was banned entirely. Anyone who broke the no-alcohol rule or caused trouble was asked to leave. They also initially avoided other modern influences like television, which Smallboy believed could reintroduce the same negative forces that they had tried to leave behind.

Robert Smallboy served as the camp’s undisputed leader and spiritual chief. The people around the council fire agreed upon this role and made daily decisions accordingly. His words held significant weight, and he steadfastly upheld the camp's autonomy and its guiding principles.

Almost immediately after their dramatic departure, the federal government weighed in, claiming the group were squatters on Crown land. Authorities made several efforts to convince Smallboy’s followers to return to the reserve, but he resisted. He argued—both publicly and in the media—that the Kootenay Plains were part of his traditional territory and had never been properly surrendered under treaty.

That claim wasn’t easily dismissed. It later emerged that this area had not been clearly included in Treaty 6 or Treaty 7 in the 1870s. It was only later associated with Treaty 8 by more distant bands, making it something of a legal grey area.

Smallboy boldly declared, “The treaty process had been a fraud… This land has not been ceded to Queen Victoria.” Holding to this belief, he asserted his right to occupy the land as an “Indian encampment” and welcomed any Indigenous person who wanted to return to the old ways to join him there.

Surprisingly, the authorities ultimately left the camp alone. Likely because no serious laws were being broken and the community remained peaceful.

At the time, news reports raised concerns about healthcare in the camp. Smallboy replied confidently, “We have our own medicine.” When journalists questioned the lack of formal religious services, he responded, “We will teach them the right way of life ourselves.”

In those early days on the Kootenay Plains, life at Smallboy Camp was rustic but well-organized, grounded in Cree traditions. Families lived in canvas tents or teepees, clustered together on the open plain. They had no running water or plumbing and drew their water from nearby creeks and the North Saskatchewan River.

Residents depended on hunting, fishing, and gathering from the surrounding foothills. Elders taught younger members how to snare rabbits, hunt wild game, catch fish, and collect berries and medicinal plants in season. This way of life not only sustained the camp, it also passed down essential knowledge of the land.

Spiritual and cultural practices quickly became central to daily life. With no Indian agents or missionaries overseeing them, Cree families could once again hold ceremonies freely. Sweat lodges, pipe ceremonies, and other traditional practices took place regularly. A large council tipi served as a gathering place for prayer, drumming, storytelling, and teachings.

“We didn’t have to hide anymore,” recalled Lillian Shirt, a Cree activist who joined the camp in 1969. As a child, Lillian had been taught to fear punishment for practicing her culture, since Indigenous ceremonies had been discouraged or outright banned in Canada for generations. But at Smallboy Camp, she witnessed a full and open revival of Cree spirituality.

“I was still scared, and I’d say, ‘What if the cops come?’” she remembered. But no one came. No one interfered. That sense of safety allowed Cree religion and ritual to flourish as a cornerstone of daily life in the camp.

To be clear, though, life at the camp wasn’t always easy, especially at the start. The first winter was particularly harsh, especially for those who weren’t used to living traditionally. Some later described it as hell. But the group stuck together and got through it, helping each other adapt to the elements.

One early attempt by the government to force people back to the reserve was based on school attendance laws. Officials argued that children in the camp weren’t being properly educated. But Chief Smallboy had always intended for the children to receive an education. However, he had no intention of sending them away for their education.

Once the government realized they had no legal grounds to enforce a return, they agreed to support education on-site. They supplied two mobile construction trailers to serve as classrooms and sent a teacher in 1969.

That arrangement didn’t last. The teacher soon packed up and left after realizing they weren’t suited for life in the bush, taking one of the trailers with them.