Flames licked the walls of the Parliament building in Montreal, casting an eerie glow across the night sky of April 25, 1849. Inside, librarians and politicians scrambled desperately to save what they could as an angry mob stormed through the halls.

Books: 12,000 volumes of Canadian history, law, and literature, sat vulnerable on shelves as the fire spread. In moments, centuries of knowledge would be reduced to ash and cinder.

Only 200 volumes would survive this catastrophic night, marking one of the most devastating cultural losses in early Canadian history.

This was just one dramatic chapter in the surprising saga of Canadian books; a story of preservation and destruction, of resilience and reinvention, that stretches from Indigenous oral traditions to the digital age.

Through fire, censorship, and technological revolution, Canada's literary heritage has endured, each saved volume a monument to those who recognized that a nation's books are the keepers of its soul.

Canadian book history is much more interesting than it may sound.

It’s probably something that most of us take for granted, or may even wonder if it will be relevant as we enter into the era of AI (or artificial intelligence). Today, we’ll uncover how Canadian books developed and evolved through the influences of diverse language traditions, including Indigenous oral cultures, French colonial writings, and English settler literature, from pre-Confederation times to the modern digital age.

We’ll explore examples of the earliest books created in Canada, the rise of libraries and publishing, important authors and works in context, the disasters and censorship that threatened literary heritage, and the evolution of publishing from print to digital and AI.

Now, the topic of Canada’s “book history” is pretty broad and slightly ambiguous.

If you’re like me, then the first type of book you might think about is the kind that tells a story. While there are lots of other types of books like textbooks, encyclopedias, or other reference books that don’t tell stories, I think it makes sense to set those aside for now, (don’t worry, we’ll get back to them in a bit), but first let’s start our investigation of the roots of Canadian book history by thinking about stories.

Or even better, because all stories are narratives, let’s begin by looking at narratives.

The Earliest example of Narrative Traditions we have in Canada comes to us from Indigenous Oral Traditions and Early pre-contact Writings. Long before Europeans arrived, the Indigenous peoples who lived on the land we now call Canada maintained dynamic oral traditions. Stories, histories, and knowledge were passed down verbally, and through memory aids like wampum belts and birchbark scrolls.

These oral literatures formed the foundation of Indigenous society, connecting speaker and listener in a shared, communal experience.

Unlike European societies, the idea of a bound book or a written alphabet wasn’t central to the cultures that have lived here since time immemorial. Instead, knowledge lived in the storyteller and in the spoken word.

Oral narratives taught lessons, passed on history, entertained, and honoured ancestors and the ancestral past. Some cultures also used symbols, patterns, knots, beads, stone etching, and birch bark scrolls to convey stories and meaning, but these didn’t take the form of books as we typically think of them.

Because this episode focuses on the history of books, specifically written and recorded texts, we’ll be tracing that particular topic. But please don’t take that to mean I’m dismissing or devaluing the incredibly rich, diverse, and vital systems of communication that were already in place long before Europeans arrived.

We now know that Europeans brought many things with them to Canada, some good and some bad. One thing you might not think about when you picture the first settlers sailing across the Atlantic in the early 1600s is that they packed books aboard their ships. When they landed, these books were the first known to be found in Canada.

As colonization continued in the 17th century, some Indigenous narratives began to be recorded in writing, often by missionaries or colonial intermediaries who used their own alphabets and language to capture what they were hearing.

One of the earliest milestones in attempting to authentically capture an Indigenous language came in 1840, when a Methodist missionary named James Evans created a written system for the Cree language.

He developed a syllabic script and set up a small printing press at Norway House, in what’s now Manitoba. Using hand-cast type made from local materials, Evans printed the first texts using Cree syllabics. Those early printings were mostly of hymns and religious teachings. It was the first time an Indigenous language had ever been printed in Canada’s West, transforming spoken Cree traditions into written ones.

By the mid-19th century, Indigenous voices themselves entered print instead of having to rely on colonials to document things on their behalf. Kahgegagahbowh (George Copway), an Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) from Upper Canada (now Ontario), published his autobiography The Life, History and Travels of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh in 1847.

That book is recognized as the first book written and published by an Indigenous Canadian, and it quickly ran through multiple editions. In the book, Copway vividly described his youth, culture, and travels, offering one of the first, first-person Indigenous perspectives available in book form.

Toward the end of the 19th century, E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), a poet of Mohawk and English heritage, rose to prominence. She’s often hailed as Canada’s first widely recognized Indigenous literary figure. Johnson became famous for her live poetry performances and published works, which resonated deeply with settler audiences, helping them feel more connected to the land they now called home.

Many of her works, like the 1895 poetry collection The White Wampum, were published in book format. I could dedicate a whole episode or series to Johnson, and I encourage you to check out some of her poetry. Selections from the White Wampum reflect the rich heritage and traditions of Indigenous people, particularly the Iroquois and Mohawk tribes, as they explore themes of love, identity, and the impacts of colonization.

Her poems often feature strong characters like warriors, lovers, and mothers, sharing their joys, their pain, and their hopes for peace and understanding in a world that felt anything but peaceful. Johnson’s voice emerges as a bridge between cultures, celebrating her Indigenous roots while highlighting the profound challenges faced by her community, ultimately calling for empathy and recognition of their struggles.

Johnson’s book success also marked a bridge between oral storytelling and print. She brought Indigenous themes to the stage and page, extending the reach of oral tradition further into the literary mainstream.

No doubt, paving the way for the many successful Indigenous authors we now find on bookshelves, ereaders, and bestseller lists. Brilliant authors such as Basil H. Johnston, Richard Wagamese, Thomas King, Katherena Vermette, Tomson Highway, and Markoosie Patsauq, to name a few. All of whom are excellent storytellers and have crafted compelling narratives.

While Indigenous storytelling has the deepest roots here, another body of literature began to take shape during the early colonial period, this time from the pens of French explorers, missionaries, and settlers.

The earliest written narratives from what would become Canada came from French colonial voices in the 16th and 17th centuries. Though New France had no local printing presses or bookstores during its existence, many important texts were written in the colony and later published in Europe.

One of the first such works was the account of Jacques Cartier’s voyages. Cartier’s Brief Récit of his 1535–36 journey up the St. Lawrence was published in Paris in 1545, giving Europeans their first detailed description of the “Canadas.” Over the next century, foundational texts of Canadian history and geography appeared.

In 1603, Samuel de Champlain published Des Sauvages, an ethnographic report of his encounters with Indigenous peoples, followed by his extensive journals of New France in 1613 and 1632.

One of the earliest major works of French Canadian literature was Marc Lescarbot’s Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, published in Paris in 1609. Lescarbot was a Parisian lawyer who spent 1606–07 in Port-Royal (Acadia). His history of New France combined travel narratives with observations of the land and its peoples.

It’s worth mentioning that Lescarbot also penned a play, Théâtre de Neptune, performed at Port-Royal in 1606, that is often cited as the first theatrical production in North America.

Other colonists and missionaries followed with writings of their own. Among the most well-known were the Jesuit Relations, a series of annual reports beginning in 1632. These documents offered vivid accounts of Indigenous life and detailed the missionaries’ efforts in New France.

But while these reports were written with care and detail, they were never intended for a mass audience within the colony itself. In New France, literacy was limited. Fewer than half of the colonists could read or write in the 17th century, and colonial authorities tightly controlled the flow of information.

Printing presses were actually banned or discouraged by French colonial policy, so any literature had to be handwritten or sent back to Europe for publication.

Despite this, a reading culture did exist among clergy and officials. Religious orders accrued libraries of manuscripts and imported books. For example, the Jesuit college in Quebec (est. 1635) maintained a significant collection of books for study. So, while no books were printed in New France itself, the French colonial period produced letters, memoirs, and histories that form the earliest Canadian literature in the French language.

After the fall of New France in 1760, French-Canadian literary activity entered a quieter phase under British rule. It wasn’t until the 19th century that a distinctive French-Canadian literature would blossom in print.

One early novel often credited as the first by a French Canadian is L’influence d’un livre (1837) by Philippe-Ignace Aubert de Gaspé (fils). A more celebrated work came from his father: Philippe-Joseph Aubert de Gaspé’s Les Anciens Canadiens, published in 1863, was a historical romance set in New France. It became the first French-Canadian literary success on a commercial scale, widely read in Quebec and soon translated into English.

Les Anciens Canadiens offered a nostalgic portrayal of life before the Conquest and is now considered a classic of Quebec literature. The warm reception of both the novel and his later Mémoires marked a turning point, as French Canada began to reclaim its literary voice with stories that preserved its history and identity under British rule.

Meanwhile, on the English side of the colonial divide, a different literary tradition was beginning to take shape. English-language writing in Canada began to flourish after Britain gained control of former French territories in 1763, as well as in the older British colonies of Atlantic Canada. Early English Canadian literature was often the work of visitors or recent immigrants describing the new land to readers back in Europe.

One early example worth noting is The History of Emily Montague, a novel written by Frances Brooke during her time in Quebec shortly after the Conquest. It was published in London in 1769 and is often described as the first Canadian novel, since it was both written in Canada and set here.

The story unfolds through a series of letters and offers a snapshot of life in 1760s Quebec, including reflections on the relationships between English, French, and Indigenous people. It’s one of the earliest English-language books that gives us a look at Canada during the early years of British rule.

Literature also began to emerge in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in the Atlantic regions, where British settlements had been established earlier than in other parts of what would become Canada.

One notable figure was Thomas McCulloch, a Scottish-born educator and Presbyterian minister who settled in Nova Scotia. In the 1820s, he became known for his sharp satirical essays and commentaries on colonial society. Through pieces like Letters of Mephibosheth Stepsure, McCulloch critiqued everything from religious dogma to the state of public education, using wit and humour to push for reform.

His writing helped shape early Canadian intellectual life, especially in the Maritimes.

Around the same time, another voice from the region was Oliver Goldsmith (not to be confused with his famous great-uncle, the Irish poet of the same name). This younger Goldsmith, born in Nova Scotia, wrote The Rising Village in 1825 as a direct response to his uncle’s more pessimistic poem The Deserted Village.

Where the elder Goldsmith mourned the decline of rural life in England, the Canadian-born Goldsmith painted a hopeful picture of progress and development in colonial life. His poem offered an early attempt to define a uniquely Canadian identity through literature, celebrating hard work, prosperity, and the promise of the land.

While its tone might strike modern readers as overly optimistic or colonial in outlook, it remains one of the first works of Canadian poetry published in English and serves as an early literary reflection of settler life in Atlantic Canada.

However, the first novel written by a Canadian-born author and published on Canadian soil was Julia Catherine Beckwith (later Hart)’s St. Ursula’s Convent; or, The Nun of Canada, printed in Kingston in 1824. Born in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Beckwith had started writing the novel when she was just 17.

Her story blended romance, religious themes, and Gothic elements, which were all common traits of the popular novels of the time. But it was also rooted in a uniquely Canadian setting, which is what made it really stand out.

Getting the book published wasn’t easy. She had to convince a local printer to take it on, and only a small number of copies, records state 165, were ever printed. Still, the achievement was significant. Beckwith became the first Canadian-born novelist to have a book published in the country, at a time when almost all books available in British North America were imported from Europe.

Her work has largely faded from the spotlight today, but it marked a meaningful first step in the development of homegrown Canadian literature.

By the 1830s and 1840s, a distinctly Canadian voice was beginning to take shape in English literature. One of the key figures from this period was John Richardson, a Canadian-born writer and veteran of the War of 1812. Drawing on his military experience and knowledge of the frontier, he published Wacousta in 1832.

That book was a dramatic historical novel set during Pontiac’s Rebellion in the 1760s. The story is packed with adventure, tension between settlers and Indigenous groups, and themes of identity and revenge. Wacousta is often cited as the first truly significant Canadian novel written in English, not only for its setting and subject matter, but for its attempt to create a national literature rooted in the Canadian experience.

Around the same time, Thomas Chandler Haliburton of Nova Scotia was gaining international attention for something entirely different: satirical humour.

Beginning in 1836, Haliburton published The Clockmaker, a series of sketches that introduced readers to Sam Slick, a fast-talking Yankee clock peddler with sharp observations about colonial life. The character became wildly popular for his wit, cynicism, and folksy charm, and the series eventually ran to three volumes. Haliburton’s writing, filled with political commentary and cultural satire, poked fun at both American and colonial Canadian attitudes.

His use of dialect and comic timing was groundbreaking at the time, and it helped establish him as one of the earliest Canadian authors to find a wide readership outside of Canada. Today, Haliburton is often recognized as Canada’s first internationally successful author and one of the first to make it into literary anthologies.

Immigrant writers who settled in Canada played a big role in shaping early Canadian literature. Two of the most well-known were sisters Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill, who emigrated from England in the 1830s and settled in what was then Upper Canada. Both wrote honestly and in great detail about the challenges of pioneer life, but it was Moodie’s memoir, Roughing It in the Bush (1852), that really stood out.

The book gained a lot of attention for its raw, unfiltered portrayal of the hardships settlers faced, from isolation and illness to harsh winters and tough farmland. It quickly became her most well-known work, going through multiple editions in Britain and the United States. Interestingly, it wasn’t published in Canada until 1871, and when it finally was, the reaction was mixed. Some Canadian readers felt Moodie had been too harsh or too critical of Canadian society.

Even so, Roughing It in the Bush has since become a cornerstone of Canadian literature, valued for both its historical insight and its literary merit. The conversations it sparked, especially around how newcomers saw and judged Canada, marked one of the first times a Canadian book really stirred public debate about national identity.

Moodie even felt the need to respond to some of those criticisms in her later writing, which shows just how seriously these early literary voices were being taken.

By the time Canada became a country in 1867, English Canadian literature was coming into its own. Writers continued to draw on their experiences in the colonies, capturing the land, the people, and the struggles of everyday life through travel writing, social commentary, and fiction.

As we’ve seen, those early works helped lay the foundation for a growing literary culture. With Confederation came new momentum, and by the late 19th century, Canadian writers were being supported by a slowly expanding network of publishers, periodicals, and public libraries.

But before that momentum could take hold, the groundwork had to be laid. The story of Canadian literature is also the story of how books came to be made here in the first place, starting with the arrival of the printing press.

As you may know, Germany’s Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable type press in the mid-1400s, transforming bookmaking across Europe and making printed material more accessible than ever before. But nearly three hundred years would pass before the first printing press arrived in what would become Canada.

In 1751, the first printing press finally arrived, brought by a printer named John Bushell from Boston. He set up shop in Halifax, Nova Scotia, a settlement that had only been founded a few years earlier, in 1749. On March 23, 1752, Bushell produced the first Canadian-printed publication: the inaugural issue of The Halifax Gazette, which became the country’s first newspaper. Because of this, he’s remembered today as Canada’s first printer.

Over the next few decades, the printing press slowly spread to other colonies. In Quebec, the first press was established in 1764 by William Brown and Thomas Gilmore, shortly after New France fell to the British. That same year, they launched La Gazette de Québec / The Quebec Gazette, a bilingual newspaper that marked the end of the French regime’s long-standing ban on printing.

In 1785, Brown also printed one of the earliest books in Quebec, a medical pamphlet titled Direction pour la guérison du mal de la Baie St Paul.

In New Brunswick and Newfoundland, a man named John Ryan would be instrumental in both provinces. In 1784, the same year New Brunswick was carved out of Nova Scotia, Ryan and his partner William Lewis set up the province’s first press in Saint John. Then, in 1806, Ryan moved to St. John’s and established the first printing press in Newfoundland, where he printed the colony’s first newspaper and official government proclamations.

Prince Edward Island, which was then called Isle Saint-Jean, saw its first press arrive in the mid-1780s. Around 1787, James Robertson, a Loyalist from the newly independent United States, began printing in Charlottetown. He produced The Royal American Gazette, the colony’s first newspaper. Like Robertson, John Ryan had also been a Loyalist.

It’s worth pausing here to explain why so many of Canada’s early printers, like James Robertson in PEI or John Ryan in New Brunswick and Newfoundland, were Loyalists from the United States.

At the time, printing was already well established south of the border. The American colonies had their first press way back in 1638, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, more than a century before the first press appeared in Canada.

Cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia had thriving publishing scenes, with newspapers, pamphlets, and political tracts in constant circulation. Meanwhile, printing in Canada had been restricted under French rule, and even under British rule, it was slow to spread.

That all changed after the American Revolution, when thousands of Loyalists, people who had stayed loyal to the British Crown, fled the newly formed United States and resettled in places like Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, and Prince Edward Island. Among them were experienced printers who brought not just their skills, but their actual printing presses with them.

In a very real way, Canada’s early publishing industry was built by exiles, refugees who packed up their livelihoods and started over. They brought the tools, the know-how, and the drive to start newspapers and printing businesses in places that had never had them before. Without that sudden wave of Loyalist expertise in the 1780s and 1790s, Canadian printing would have likely developed much more slowly.

But getting back to Canada, the first press in Upper Canada (Ontario) was established in 1792 at Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) by Louis Roy. Roy, under the patronage of Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe, printed the first Upper Canadian newspaper (Upper Canada Gazette) and other official notices. By the 1810s, presses appeared in Kingston and York (Toronto) as well.

By the end of the 18th century, all the eastern provinces of Canada had local printing presses in operation. But as we’ve seen, this initial spread was pretty slow. It took around half a century after the first press arrived in Halifax to reach all corners of the colonies.

And even then, just having a printing press wasn’t enough. Keeping it running in the rough conditions of colonial Canada was a challenge in itself.

Early printers often faced a constant shortage of supplies. Paper was expensive, metal type had to be imported or reused, and skilled labour was hard to come by. Despite these obstacles, they managed to produce an impressive range of printed material: newspapers, government notices, almanacs, and the occasional book or pamphlet.

Most of these were small-run and practical, meant for immediate use rather than preservation. That’s why surviving examples are so rare today. Library and Archives Canada holds only about 500 items printed in Canada before 1800. When new ones occasionally do surface, it’s a big deal because each one adds to a very limited record of our earliest printed history.

West of Ontario, printing arrived even later, often under frontier conditions. In Manitoba, Missionaries introduced printing to the Red River area. As mentioned earlier, in 1840, Reverend James Evans began printing religious texts in the Cree syllabic script at the Rossville Mission (Norway House) using a makeshift press and homemade type. A secular press arrived almost two decades later, in 1859, with the launch of the Nor’Wester newspaper at Fort Garry.

The Fraser River Gold Rush in 1858 brought a surge of population to BC, and with it came an appetite for news. That year, five newspapers launched in Victoria, including The British Colonist, founded by Amor De Cosmos, who would later become Premier. The hand presses used to print them had just made it into the colony, arriving hot on the heels of the prospectors who were pouring into the west.

The first printer in what is now Saskatchewan was Patrick G. Laurie, a Scottish immigrant who hauled a printing press by ox cart over 1,000 km from Winnipeg to the frontier town of Battleford. Can you imagine what a long and arduous task that would’ve been back then?

In 1878, he began publishing the Saskatchewan Herald, the territory’s first newspaper. In Alberta, a layperson serving as a missionary named Father Émile Grouard set up a press at Lac La Biche in 1876. He used it to print prayer books and, in 1878, completed Alberta’s first book, Histoire sainte en Montagnais (Montagnais was a term used for the Dene language), bringing written religious instruction to Indigenous Dene peoples.

By the 1880s, commercial presses appeared in Edmonton and Calgary as settlements grew there, too.

During the Klondike Gold Rush, a printer named G.B. Swinehart trekked from Alaska to Dawson City intending to start a newspaper. When nasty weather forced him to winter at Caribou Crossing, he improvised a single-issue newspaper, The Caribou Sun, that he published in May 1898.

This was the first document ever printed in Canada’s Arctic north. Upon reaching Dawson City, Swinehart established The Yukon Sun in 1899. From a log cabin press office, he and others served a boomtown hungry for news.

The emergence of these early presses was pivotal. It meant books and newspapers no longer had to be imported or copied by hand. Ideas could now be shared more easily and quickly through local print.

But with few resources and little infrastructure in place, much of the responsibility fell to the printers themselves. Early Canadian printers often wore many hats, acting as publishers, editors, and booksellers all at once. They also had to navigate political sensitivities.

In Montreal, for example, Fleury Mesplet arrived in 1776 and began printing newspapers and pamphlets that promoted liberty. His work eventually landed him in jail for sedition under the colonial regime.

Despite these challenges, by the end of the 19th century, a basic printing infrastructure had taken root across the Canadian provinces. One that helped lay the foundation for a homegrown publishing industry.

With that infrastructure in place, a new chapter began. Printing presses paved the way for the rise of publishers who began producing books, magazines, and newspapers for profit.

Initially, most publications were small-run and locally focused. Newspapers soon spread to every colony and town, fueling public debate and literacy as they grew. Many of Canada’s first books were actually printed compilations of lectures, religious tracts, or almanacs.

Things deemed more essential and practical than entertaining. For example, the Halifax Gazette printer John Howe published almanacs in the 1770s, and in 1800 the Niagara press printed an arithmetic textbook for schools.

Several notable early publishing ventures helped shape Canada’s literary landscape. One of the most influential was The Literary Garland, a Montreal literary magazine published from 1838 to 1851. It was edited by John Lovell, an Irish-born printer and publisher who had settled in Montreal and become a central figure in Canadian publishing.

The magazine featured fiction and poetry by Canadian writers, including Susanna Moodie, and played a key role in building a readership for homegrown literature. But Lovell wasn’t just an editor, he also went on to become one of the most important publishers in pre-Confederation Canada. His company, John Lovell & Son, published a wide range of books and, in 1855, produced Canada’s first general encyclopedia.

His work helped bridge the gap between traditional printing and literary publishing, laying the groundwork for more ambitious Canadian publishing ventures in the years ahead.

By the mid-19th century, bookshops in cities like Toronto and Montreal were regularly importing and selling books, both British and American. Some booksellers went a step further and became publishers themselves. For example, in addition to selling books, in Toronto, Henry Rowsell also published Canadian-authored works, including an 1853 edition of Moodie’s Roughing It in the Bush.

The late 19th century saw the rise of dedicated publishing houses that would go on to define Canadian literature in the next century. Around this time, firms like Musson Books, Hunter, Rose, and several others began to emerge. These companies started to recognize the value of publishing Canadian manuscripts, rather than acting solely as distributors for British titles.

This shift didn’t happen in isolation. Canadian authors were also beginning to break through to wider audiences, both at home and abroad. Although many still had to publish in the U.S. or U.K. for better distribution, their success played a key role in encouraging local publishers to take Canadian voices more seriously.

As well as Haliburton’s Sam Slick sketches, Goldwin Smith’s histories and Charles Heavysege’s epic poem Saul, printed in Montreal in 1857, also drew international attention. B

y the 1880s, a group of poets known as the Confederation Poets—Charles G.D. Roberts, Archibald Lampman, Bliss Carman, and Duncan Campbell Scott—were publishing critically acclaimed volumes of verse. Their literary achievements helped prove that Canadian writing could hold its own on the world stage.

By the early 20th century, that momentum helped pave the way for a new generation of publishers. In 1907, John McClelland and Frederick Goodchild founded a Toronto-based publishing firm, later joined by George Stewart. At the time, McClelland was still in his teens and just getting started in the business. Goodchild brought early experience, and Stewart helped guide the company in its formative years.

That firm would eventually become McClelland & Stewart, one of the most iconic names in Canadian publishing. Though both Goodchild and Stewart moved on, McClelland remained and would go on to become one of the most influential figures in the history of Canadian literature. Under his leadership, the company championed Canadian writers well into the 20th century and helped shape a national literary identity.

The advent of mass publishing technology in the 19th and 20th centuries (steam presses, linotype, etc.) dramatically lowered the cost of books. By the late 1800s, literacy rates were climbing in Canada, due in large part to public education.

In the early 17th century, less than half of the settlers in New France were literate. By Confederation (1867), most regions with schooling had majority literacy, although Quebec’s rates lagged behind Ontario’s due to less comprehensive schooling. The push for free, compulsory education in the late 19th century meant that by the early 20th century, a vast majority of Canadian youths learned to read and write. This created a mass reading public.

Cheaper printing led to serial novels and newspapers that a working-class family could afford. Where a bound book in 1750 might cost a week’s wages, by 1900, a dime novel or newspaper cost cents. The rise of public libraries (as we’ll soon discuss) also made reading material free for borrowers. All these factors democratized access to literature.

The turn of the 20th century also brought Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables (1908), which was published in Boston but authored on Prince Edward Island. It became a global phenomenon, selling over 50 million copies. This showed the commercial potential of Canadian stories and encouraged more domestic publishing. By the 1920s, Canada had a small but solid publishing industry, with both educational texts and literature being produced consistently.

The establishment of the Canadian Authors Association in 1921, followed by the launch of the Governor General’s Literary Awards in 1936, helped further legitimize writing as a profession in Canada.

These institutions gave authors formal recognition and advocacy at a time when few made a living through writing alone. In countries like Britain and the United States, similar literary institutions, such as the Pulitzer Prize (established in 1917) or the UK’s longstanding literary societies, had already been promoting national literature and supporting authors.

But for readers in Canada, finding our stories wasn’t always easy. Access to books in early Canada often depended on private and institutional libraries, well before public libraries became common.

The very first library in Canadian history was a private collection: Marc Lescarbot’s library, which he brought with him to Port-Royal, Acadia in 1606. Lescarbot’s books, consisting of volumes of law, history, and literature, were the first known collection of European books on Canadian soil.

This small library provided entertainment and knowledge for the colonists. Lescarbot even used these books to educate and amuse his fellow settlers during the long winters.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, libraries in Canada were typically found in religious institutions or the homes of officials. When the Séminaire de Québec (later Laval University) was founded in 1663, it had a library that grew in importance over time. By the 1750s, a substantial Jesuit library existed in Quebec City; Swedish botanist Pehr Kalm noted its presence when he travelled through the city around that time.

In 1773 by Pope Clement XIV due to political pressure from European monarchs who viewed the Jesuits as too powerful and independent. Monarchies in Portugal, France, and Spain had grown suspicious of the order’s influence in both religious and political affairs, and pushed for its global dissolution.

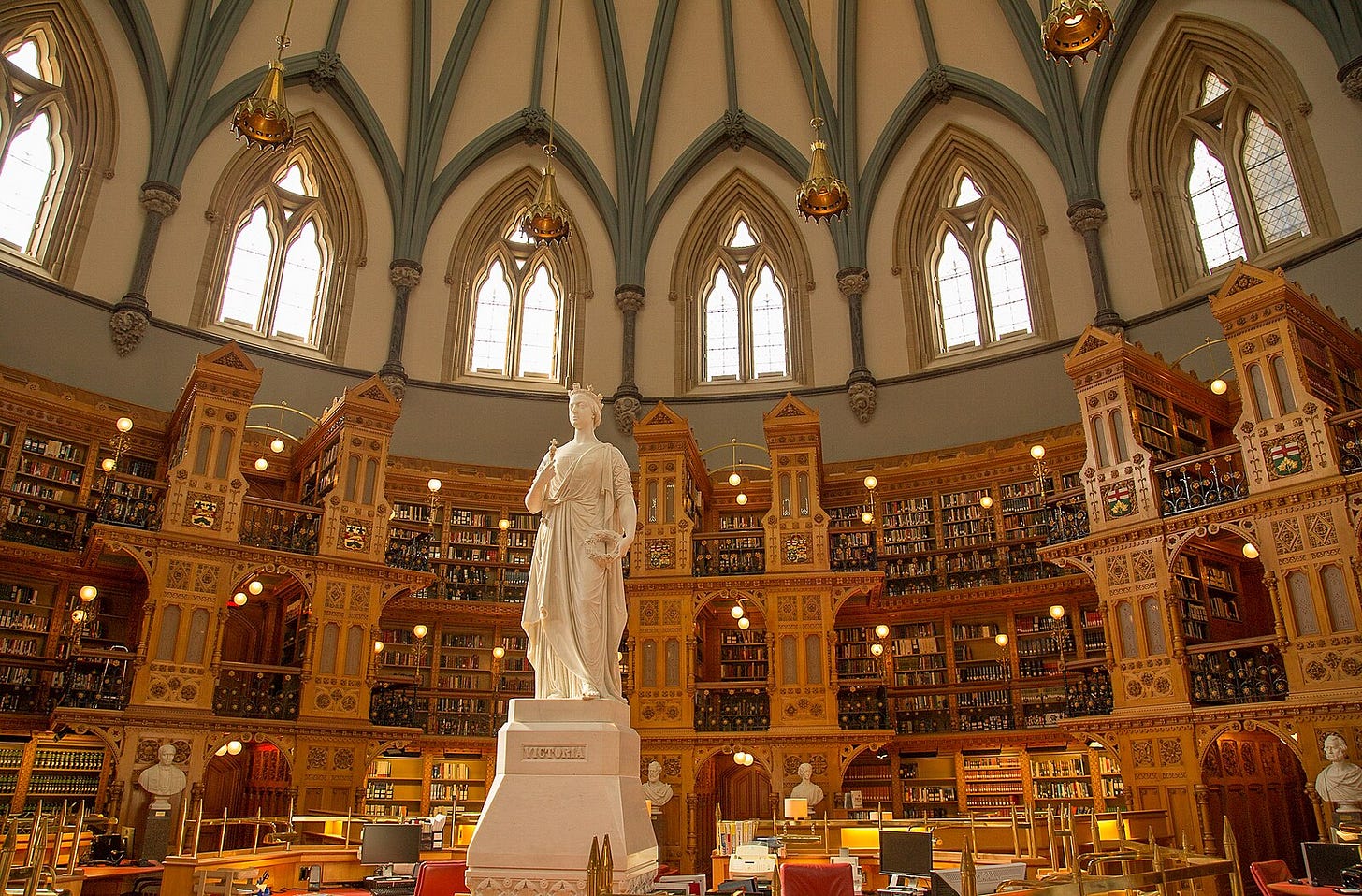

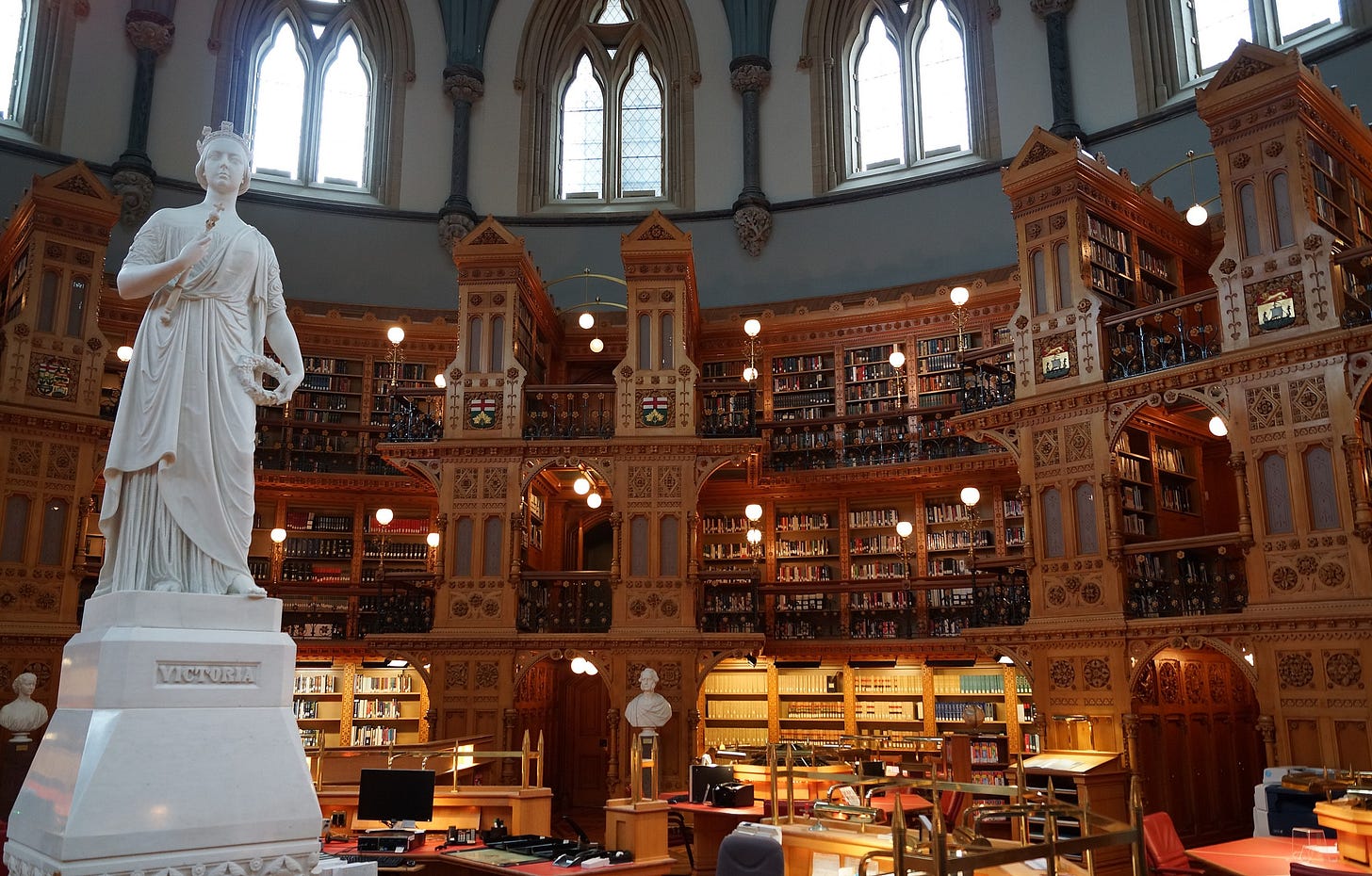

In Quebec, the Jesuits had amassed one of the largest libraries in the colony at their college in Quebec City. When the order was disbanded, that collection survived intact. It was first sold to the Quebec Gazette newspaper, and later, in 1851, to the Library of Parliament. Remarkably, those same volumes endured two major fires over the years and are still preserved on Parliament Hill today, one of the oldest surviving colonial-era book collections in the country.

Before public libraries, General James Murray in Quebec and Governor Frederick Haldimand accumulated significant collections of books and maps. In 1779, Governor Haldimand founded a subscription library in Quebec City, one of the first organized libraries open to members of the public (subscribers) in Canada.

In Montreal, after the British takeover, learned societies also formed libraries, and a Bibliothèque was opened in Montreal by 1796, just a few years after the city’s first newspaper began.

Legislative libraries were also among the first stable library institutions in Canada. Prince Edward Island’s colonial legislature established a library in 1773, making it one of the country’s oldest continuously operating libraries.

In the 1790s, both the Parliament of Upper Canada (Ontario) and Lower Canada (Quebec) created libraries to serve their lawmakers. Upper Canada’s began in 1791, and Lower Canada’s followed in 1792. These collections focused on books about law, politics, and history, and were intended to support legislative work. Over time, they evolved into the provincial legislative libraries that still operate today.

The Library of Parliament for the united Province of Canada was created in 1841, merging the Lower and Upper Canada assembly libraries. This library became somewhat mobile as it had to travel to each new capital city each time it changed from Kingston to Montreal to Toronto and Quebec City.

Despite its nimbleness, it also faced serious adversity. In 1849, a riot broke out in Montreal after the controversial Rebellion Losses Bill was passed, compensating people in Lower Canada for property damaged during the rebellions of 1837–38. An angry mob stormed the Parliament buildings and set them on fire. In the blaze, the parliamentary library lost nearly all of its holdings.

Only 200 of 12,000 volumes survived. It was one of the most devastating cultural losses of early Canadian history.

Then, after rebuilding the library, another fire in Quebec City in 1854 destroyed part of the collection again. These disasters actually prompted important improvements. When a permanent Parliament was built in Ottawa, librarian Alpheus Todd insisted on fireproofing measures, including the iron fire doors that famously saved the Library of Parliament from the great fire of 1916.

The Library of Parliament (completed 1876) still stands today as an architectural icon and guardian of a collection that dates back to those early legislative libraries. It even appears on the Canadian $10 bill as a symbol of our knowledge heritage.

During the 19th century, access to books started to gradually broaden. Mechanics’ institutes (adult education centers for workers) sprang up in many towns (e.g. Toronto Mechanics’ Institute, 1830). They often had reading rooms and lending libraries. However, these were membership-based.

But the idea of free public libraries began to take hold in the mid-to-late 19th century, inspired by growing literacy rates, industrialization, and a rising belief in education as a public good. In both Britain and the United States, public libraries were seen as a way to support self-improvement, moral education, and civic participation, especially for the working class.

That same thinking eventually reached Canada, where early efforts to expand access to books built on the foundation of subscription libraries and Mechanics’ Institutes.

According to one historical survey, the first free public libraries in Canada opened in 1883, in Guelph and Toronto. In Toronto’s case, the city took over the local Mechanics’ Institute library to create what became the Toronto Public Library. Guelph’s library, also founded that year, was supported by a combination of public funding and private donations.

Once the idea of public libraries caught on, the movement spread quickly. By the early 20th century, dozens of Canadian cities and towns had established free libraries, recognizing them as essential community institutions.

Many benefited from the philanthropy of American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, whose foundation provided grants for library buildings. For example, Carnegie grants helped build libraries in Ottawa (1906), Winnipeg (1905), Vancouver (1903), and over 100 communities across Canada, including my little hometown of Owen Sound, Ontario.

For context, Andrew Carnegie was a Scottish immigrant who went on to make a fortune in the steel industry. He later donated over fifty million dollars worldwide for the construction of free public libraries. He was once quoted as saying,

“What is the best gift which can be given to a community? … a free public library occupies the first place…”

- Andrew Carnegie, 1889.

Carnegie's funds greatly expanded Canadian library services in the 1900–1920 period. In addition, provinces began to pass library acts to support rural and regional library systems. “Travelling libraries,” which were programs that sent boxes of books to remote areas, were tried in the West to reach farm communities, too.

Canada also developed major library institutions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Dominion Archives was founded in 1872 (the precursor to Library and Archives Canada). It focused on preserving historical documents.

And then a true National Library of Canada was established in 1953. It merged with the Archives in 2004 to form today’s Library and Archives Canada. These national institutions continue to coordinate the preservation of Canadiana and access to information across the country.

Publishing rights and copyright in Canada also evolved at this time. In the early days, Canadian authors often had tenuous rights. Prior to Confederation and for decades after, British copyright law applied. Canadian colonists had little protection if their work was pirated abroad. For instance, many Canadian and British books were reprinted cheaply in the United States in the 1800s due to weak international copyright.

Canada passed its first colonial copyright statute in 1832 (in Lower Canada) to secure rights for authors, but it wasn’t very effective internationally. After becoming a country, Canada eventually enacted its own Copyright Act in 1921 (effective 1924), joining the Berne Convention system.

This gave Canadian authors more control and royalties for their works at home and abroad. The modernization of copyright has been crucial in supporting a robust publishing industry where authors can make a living and publishers can invest in new books. Today, the discussion continues in the context of digital copying and AI (as we will see a bit later).

While authors were gaining more control over their work, readers were also gaining more access to it, thanks to the steady growth of libraries and public literacy efforts across the country.

From Lescarbot’s lone shelf of books in 1606, Canada progressed to a nation of libraries: academic libraries in colleges since the 19th century, legislative libraries, and a widespread public library network by the mid-20th century.

This ensured that books (once scarce treasures) became increasingly available to ordinary Canadians, boosting literacy and a love of reading across the country. With all of the efforts that have gone into making books accessible, it’s little wonder that Canada consistently scores near the top of the rankings for the most literate countries in the world.

The path of Canadian books hasn’t been without its perils, though. Fire, war, and censorship have all threatened or destroyed portions of our written heritage over time. Before modern fire protection, libraries and printing offices were extremely vulnerable to fire, which is pretty obvious when you consider all of that paper sitting around.

For the first few centuries, a single spark could easily erase entire collections. As well as the 1849 Burning of the Montreal Parliament and the 1854 Quebec Parliament Fire that we touched on earlier, there have been other disasters.

In the late 19th century, several Canadian universities suffered devastating library fires. Notably, on February 14, 1890, a fire broke out at University College, University of Toronto, when two staff members accidentally dropped kerosene lamps while preparing for an evening exhibition.

The fire rapidly engulfed the eastern wing and the college library, destroying over 33,000 volumes. Despite the efforts of staff and students, only about 100 books were saved before the fire consumed the collection. The loss was significant, but the university community rallied, and within two years, the library was replenished with donations from institutions across the British Empire.

Similarly, in 1883, Université Laval in Quebec City experienced a fire that destroyed a significant portion of its library.

On February 3, 1916, the Centre Block of Parliament in Ottawa (the main building) was consumed by a catastrophic fire. Fortunately, the circular, detached Library of Parliament at the rear survived intact, thanks to those heavy iron doors and a quick-thinking librarian who ordered them shut.

While the Library (and its books) were spared, the rest of Parliament’s facilities were destroyed, and tragically, seven people died. Had the library caught fire, Canada could have lost an irreplaceable collection of historical books and archives. This event is often cited as a close call that validated the foresight of fireproof library design.

Many community libraries and bookstores have faced destruction during Canada’s history of urban fires. Each fire meant lost books that had to be replaced, if that was even possible.

Not all threats to books were physical; some were ideological. Throughout Canadian history, authorities have, at various times, banned, censored, or even destroyed books they deemed dangerous, subversive, or obscene.

In New France, strict Catholic censorship meant that Protestant or heretical works were forbidden. The colonial administrators and clergy carefully vetted imported books. Only religious texts (like catechisms) were allowed in limited handwritten copies. This early form of censorship kept New France culturally tied to the Catholic church and the French Crown.

During the Rebellions of 1837–38, both imperial authorities and rebel leaders used the printing press as a weapon. Pamphlets, broadsides, and editorials flew back and forth, each side trying to sway public opinion. Colonial officials often seized inflammatory material from figures like William Lyon Mackenzie, whose political writings were seen as threats to the established order.

In some cases, presses were physically destroyed. Mackenzie’s own was smashed by a loyalist mob in Toronto. In such a volatile climate, any printed material seen as encouraging rebellion risked being censored or shut down entirely.

One of the most notorious censorship laws in Canada was Quebec’s Padlock Law of 1937. This law, pushed by Premier Maurice Duplessis, allowed authorities to padlock (shut down) any building used to produce or disseminate “communist” materials, and to seize and destroy any publications propagating communism.

It was a blunt instrument of censorship during the period of the “Red Scare.” Under this law, leftist newspapers were closed and their literature confiscated. The Padlock Act stood until 1957, when the Supreme Court of Canada struck it down as unconstitutional (deciding that only the federal government could make such criminal law).

During its two decades, the Act cast a chill over free expression in Quebec, though in practice, relatively few people were actually prosecuted. Its legacy is still a reminder of how political fears led to the legalized destruction of books and pamphlets in Canadian history.

You might be surprised to learn that throughout the 20th century, Canadian customs officials frequently banned “obscene” or subversive books from entering the country. Classic works like Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence were prohibited in Canada for a time.

Although the novel was famously put on trial for obscenity in the United Kingdom in 1960, leading to a “not guilty” verdict for Penguin Books, Canada’s legal challenges continued into the early 1960s. In 1962, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the book was not obscene, allowing it to be legally published and sold in the country.

This decision marked a significant moment in the evolution of Canadian obscenity law and the broader conversation about literary censorship.

As progressive as we sometimes think we are, even scientific texts on birth control were once banned. Until the 1960s, Canada maintained an index of prohibited import books, which included everything from explicit literature to socialist writings. While not outright book-burning, this censorship limited what Canadians could legally read. However, many of these bans were eventually lifted as social attitudes liberalized from the late 60s through the 70s and beyond.

Though in more recent times, individual books have been challenged or removed from libraries due to content. Books dealing with topics of race, sexuality, or religion sometimes face calls for removal. Controversies have arisen over children’s books with 2SLGBTQ+ themes or novels like The Handmaid’s Tale being deemed too vulgar by some school boards.

Canada, or at least parts of it, celebrates Freedom to Read Week each year to highlight and resist such censorship. This indicates an ongoing vigilance in protecting intellectual freedom and remembering that even today, the content of books can come under fire (metaphorically speaking).

In addition to deliberate censorship of some books, another form of “loss” is the neglect or suppression of Indigenous oral literature and languages. For many decades, Indigenous stories and languages were not written down and were discouraged by Canadian policies, such as residential schools, which punished Indigenous children for using their own language.

This contributed to the decline of some oral traditions. Fortunately, recent efforts by Indigenous communities and scholars have aimed to record and revitalize these stories in print and digital forms, preserving them for future generations, while being mindful to avoid appropriating Indigenous stories and narratives.

For many Indigenous peoples, oral tradition was, and still is, a vital way to preserve and pass on knowledge. These stories, told aloud and passed from generation to generation, created a shared cultural memory long before books appeared. When European missionaries and settlers arrived, they often failed to recognize oral storytelling as legitimate history.

The absence of books was wrongly interpreted as an absence of knowledge. Over time, however, many Indigenous oral narratives were transcribed. Some by ethnographers and missionaries, others by Indigenous authors themselves.

In 1871, missionary Silas Rand published Legends of the Micmac, recording stories passed down for generations. In the North, Inuit communities worked with missionaries to transcribe storytelling in syllabics during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, many Indigenous communities are reclaiming this tradition through digital storytelling projects, recording elders’ voices and cultural memory using modern tools.

However, I mention this because we still sometimes equate an absence of books with a lack of history, stories, culture, and significance. As a historian, this is actually something I think about a lot. Some people, groups, communities, or professions are better than others, or more committed than others, or maybe more aware than others, ot the importance of recording information in books as a way to establish relevance.

This bias of book-based learning cultures to show a bias towards learning from books is something that people have leveraged for centuries to ensure legacies, knowledge transfer, and historical relevance. I think it’s something that will continue to be important for people, groups, and communities who are at risk of disappearing or being forgotten, to ensure that their history and their stories are recorded in books.

Before we move on to books in the digital age, I want to circle back briefly to a point that’s easy to overlook: European settlers, too, were once rooted in oral culture. In pioneer homes, reading aloud was a common form of entertainment. Before movies, radio, or even electricity, families would gather around letters from relatives or well-worn Bibles. Community readings, travelling storytellers, and poetry recitations helped bridge the gap between oral and literate traditions.

As printing became more affordable and books more widely available, solitary reading began to take hold. But oral and written forms never fully parted ways. Throughout Canadian history, poets and other storytellers have performed their work on stage and sold printed versions afterward. That tradition is still alive today through spoken word festivals, podcast storytelling, and livestreamed readings on platforms like Substack, Twitch, and YouTube.

Books continue to capture our attention. And while many of us read quietly in private, there’s still something deeply comforting about being read to. Maybe it’s because for so many of us, our first memories of stories are tied to someone else’s voice. As we’ll soon see, books aren’t going anywhere. They may shift in form, from bound paper to pixels on a screen, or even something entirely new, but the need for storytelling remains as strong as ever.

By the late 20th century, a new wave of change transformed the Canadian book world. The digital revolution altered how books were made, sold, and read. Perhaps more radically than anything since the arrival of the printing press.

E-books, audiobooks, and online publishing have reshaped how Canadians consume literature. Devices like Kobo (a Toronto-based e-reader company) and Kindle became common. By the mid-2020s, nearly one in five Canadians reported reading digitally, and public libraries lent out e-books just as often as they did physical ones.

Audiobook use also surged, giving readers new ways to engage with stories while commuting, exercising, or working. Publishers adapted by releasing most titles in multiple formats and reviving out-of-print works through digital editions.

Digital reading brought convenience and reach, but also challenges. Amazon and other online retailers dominated sales, putting pressure on independent bookstores. Self-publishing platforms exploded, allowing authors to bypass traditional gatekeepers. While this opened doors for niche voices, it also flooded the market, making it harder for some authors to stand out or to make a living when the competition pushes prices down as supply far outpaces demand.

At the time of writing, the newest frontier is AI-generated content. Tools like ChatGPT and Claude have raised tough questions in the book world. On one hand, AI can assist with editing, translation, and idea generation. On the other hand, it can produce entire books with little or no human input, raising concerns about quality, originality, and copyright.

Some companies remain vague about which sources were used to train their large language models (LLMs). Every few months, a new headline reveals that thousands of books were used, often without permission, compensation, or even acknowledgement. Many of these works were written by living authors who had no say in the matter.

Some writers have even left the profession in frustration, feeling that the time and effort it takes to write a book no longer pays off. Especially if their work ends up training AI systems that profit without ever giving anything back to the human creators who made it possible.

Canadian authors and publishers have responded by lobbying for stronger protections. In 2023, a coalition of Canadian publishing groups met with federal officials on World Book Day, urging transparency from AI firms and protections for the rights of human creators.

Their message was clear: creativity must be compensated. They argue that companies building generative AI owe a debt to the authors and publishers whose works fuel these algorithms. As MP Lisa Hepfner put it,

“We need writers to be paid properly… Anything that AI comes out with is being scraped from something else—there’s no human spirit, and that’s what we have to protect.”

Still, some Canadian writers are beginning to experiment with AI as a creative tool. Abroad, a Japanese AI-assisted novel has already won a literary prize. These developments hint at new possibilities, but the consensus remains: storytelling may evolve, but the human “voice” is still at the heart of it.

The voice and experiences of authors, especially in a culturally diverse country like Canada, remain unique. The human element in storytelling continues to be essential for meaning and creativity.

The shift toward digital has also meant that readers in remote parts of Canada can now access entire libraries of content instantly, a development that early colonists would have marvelled at.

From a single voice reciting a myth in an Indigenous language to a colonial scribe penning a journal by candlelight to a modern novelist’s words converted into bytes and beamed across the world, the modes have changed, but stories remain at the heart of Canadian culture.

Today, oral, print, and digital traditions coexist. At a library event, you might hear a storyteller recount a traditional tale (oral), pick up a printed novel by Margaret Atwood (print), and later download an eBook by a new Canadian sci‑fi author or listen to a serialized podcast (digital). This interplay of forms continues to enrich Canada’s literary landscape.

The history of Canadian books is a story of convergence: Indigenous, French, and English traditions flowing into a broader current. We’ve seen how the earliest works in each tradition emerged: oral epics and Cree syllabics, the chronicles of New France, and the novels of early English Canada. We traced the growth of libraries, from exclusive colonial collections to public institutions that democratized reading.

We followed the printing press as it spread westward from Halifax, enabling local voices to be shared in print. We examined how fire and censorship threatened those voices, and how rebuilding, resilience, and advocacy pushed back. And we looked at how increasing literacy, falling costs, digital publishing, and AI have transformed how books are created, distributed, and read.

Throughout this journey, a few themes stand out. First, the persistence of storytelling: whether passed down through generations or published by a major press, Canadians have always sought to tell their stories and have them heard.

Second, Canada’s cultural duality, or plurality: English and French literatures developed in parallel, often unaware of each other, while Indigenous storytelling endured in separate and often unrecognized spaces. Today, these streams are finally beginning to intertwine, with stories being translated, shared, and appreciated across languages and cultures.

Third, the growing identity and legacy of Canadian books: where writers once yearned for international validation, today Canadian authors regularly win global recognition. Books once seen as too local, like Anne of Green Gables, have become universal.

And works once deemed scandalous or unreadable, like Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, are now considered classics. This reflects how tastes shift and how innovation is eventually appreciated.

The history of Canadian books is, ultimately, a chronicle of creation, destruction, and rebirth. From the quill and ink of explorers to the bytes of e‑books, Canadian storytelling has continually adapted to new mediums.

Libraries and archives help ensure that, no matter the format, the stories endure. Today, in the digital age, the entire span of that history is at our fingertips: we can read a 400‑year‑old explorer’s journal or a brand‑new AI‑generated story with equal ease.

This legacy, safeguarded by record, memory, and care, is something Canada’s earliest printers and librarians, who laboured by flickering lamplight and defended books from flames both literal and figurative, would no doubt celebrate.

The Canadian book, in all its forms, continues to turn new pages while never forgetting the chapters that came before.

Thank you for reading this Canadian history story. It’s an absolute pleasure to share it with you. If you’re a paid subscriber, your support truly means the world to me. And if you’re reading for free, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid membership when you feel there’s enough value in my work as an independent journalist and historian to get behind it.

Pinecone Diaries is proudly 100% reader-supported.

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story

https://journals.openedition.org/eccs/3367?lang=en#:~:text=English%20%20%2018

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED118064#:~:text=The%20history%20of%20books%2C%20reading%2C,but%20the

https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/download/10971/11904/#:~:text=or%20

https://thediscoverblog.com/2018/08/28/canadas-earliest-printers/#:~:text=Johann%20Gutenberg

https://journals.openedition.org/eccs/3367?lang=en#:~:text=English%20%20%2018

Share this post