Prologue

There is something strange that happens with books sometimes.

A writer can pour everything into a story, finish it, share it with the world, and still… somehow… it disappears. Maybe not right away. Maybe it takes a few years, or even a generation. But the book slips through the cracks. It fades from conversations, from shelves, from memory. Sometimes it is simply forgotten. Other times, it is misunderstood or misrepresented.

Every now and then, when we are lucky, a book that was lost gets found again. And when that happens, it feels like a small miracle.

That’s the theme we’re exploring today. Stories about books that disappeared for a time and then, through effort or accident, were rediscovered. Stories that remind us how fragile art can be, and how resilient too.

Before we dive into our first story, I want to start with one I came across while researching the history of books in Canada. It’s a story that stuck with me.

Markoosie Patsauq grew up in Inukjuak, a northern Quebec community, during a time of massive upheaval.

In the early 1950s, his family, like many others, was uprooted by the Canadian government during the High Arctic relocations. Officials promised better hunting grounds further north. The reality was harsher. Markoosie’s family, along with others, was moved thousands of kilometers away to the stark, unfamiliar land of Resolute. They faced brutal cold, unfamiliar terrain, food insecurity, and isolation.

Markoosie lived through it. He became one of the few Inuit to pursue formal education at the time and eventually trained as a pilot. Somewhere inside all of that hardship, he began to write.

He told a story based on old tales he had heard as a boy but made it his own. A young hunter. A wounded polar bear. A journey of survival and reckoning. He wrote it in Inuktitut, his first language, and it was serialized in an Inuit magazine in the late 1960s, before being published as a book titled Uumajursiutik unaatuinnamut.

Later, a government official asked him to adapt the story into English. Markoosie could not simply translate it word for word. The languages did not match perfectly, and the audiences were different. He tried to “arrange” it as he put it, into English the best he could, but a lot of the story got lost in translation.

In 1970, his book was published in English as Harpoon of the Hunter. It quickly became a sensation. It was excerpted in textbooks and taught in schools across the country. However, the English version had been heavily edited to suit southern Canadian readers. Parts of the story were trimmed down, and the tone was softened significantly. This simplified version was classified as children’s literature, which downplayed its depth and significance.

For decades, the original Inuktitut text sat largely unread. No one published a faithful translation. When the story was translated into other languages like French, Danish, and Hindi, they based it on the English version, not the original.

Markoosie’s real voice, the voice born from Arctic hardship, family stories, relocation, and resilience, was missing from most conversations.

Then, fifty years after it was first published, something incredible happened.

Scholars finally went back to Markoosie’s original manuscript. They created a new edition that included the Inuktitut syllabics, a Romanized version for those unfamiliar with syllabics, and new English and French translations, this time working directly from the Inuktitut text.

For the first time, readers could experience Hunter with Harpoon the way Markoosie had intended. It wasn’t just an adventure story. It was a powerful work of Indigenous storytelling, lore, and survival.

Markoosie lived long enough to see this renewed interest in his work. He passed away in 2020, remembered as a pilot, a survivor, the first Inuit novelist in Canada and a literary pioneer whose voice had finally been restored to its proper place.

That’s the thing about stories. Sometimes they get buried. Sometimes they are edited beyond recognition. Sometimes they just slip through the cracks. If we’re lucky though, sometimes they get found again.

Today, I want to share three more stories of Canadian books that were almost lost, and the journeys that brought them back.

First, a Victorian-era science fiction novel from New Brunswick that vanished after its author’s death, only to resurface and earn a place in literary history.

Then, the haunting verses of a teenage poet from Montreal, whose mind slipped into madness even as his poetry became immortal.

And finally, the story of a bold woman from British Columbia who became a global celebrity with her Arctic adventure book, only to have her memory fade away almost as quickly as she had risen.

These are stories about books. They are also stories about memory, loss, rediscovery, and the surprising endurance of voices across time.

Let’s begin.

Story 1

Sometime in the early 1860s, though we don’t know exactly when, a New Brunswick-born writer named James De Mille sat down, maybe by the warm light of a whale-oil lamp, and wrote a story about an English sailor who finds himself stranded on a strange, uncharted island in the Southern Ocean, what we now call the Antarctic Ocean.

It’s a wild story about a hidden race called the Kosekins, who survive in a world where giant birds wheel overhead, reptilian beasts roam misty swamps, and ancient sea monsters lurk just beneath the black waters offshore. A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder is probably the first Canadian science fiction story ever written.

My guess is you’ve probably never heard of it. While science fiction isn’t for everyone, even among hardcore fans of the genre, this pioneering work isn’t well-known.

What fascinated me when I came across it was that it may never have been published at all. Although James De Mille wrote it in the 1860s, it wasn’t published until 1888. That was eight years after he passed away. De Mille had died suddenly in Halifax on January 28, 1880, at the age of 46, leaving behind reams of draft stories, notes, and book ideas.

Years after his death, while sorting through the stacks of paper he left behind, his family came across a nearly complete manuscript for A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder. They decided to publish it. Its release added to De Mille’s already impressive collection of published works.

See, De Mille was actually one of the most prolific and well-known Canadian authors of his time. Over his life, he published more than 30 novels, a textbook, and other literary pieces. His first book came out in 1864. Most of his others were published during the last ten years of his life, which means he was cranking out an average of two novels a year. That’s an incredible amount of writing.

And yet, much like A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, not many people today have heard of James De Mille, despite the incredible success and popularity he enjoyed during his lifetime.

Let’s change that now. Let’s look back at this forgotten author and his most famous book, the one that was almost never published, and that he never got to see in print.

James was born in Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1833. He was the third child of Nathan Smith De Mille and Elizabeth Budd. James’s father, Nathan, was a fairly prosperous merchant and shipowner who later worked in the lumber industry in Saint John. He also served on the Board of Governors at Acadia College.

James and his brothers attended Horton Academy in Wolfville before continuing their education at Acadia in 1850. A few years later, James earned his master’s degree at Brown University in Rhode Island, graduating in 1854.

After finishing his studies, James spent a year travelling with his brother, Elisha Budd De Mille. They took a steamer to Boston, rattled inland by train to Quebec, and then climbed aboard one of their father’s stout wooden boat bound for England.

Once overseas, the brothers spent months walking country lanes under the heavy gray skies of England, hiking misty hills in Scotland, and winding through the bustling streets of Paris, before making their way to Italy. In Italy, as he visited crumbling ruins from ancient history, and all sorts of significant sites from the classical era, James developed a real passion for Italy’s rich culture and vast history.

It’s said that his experiences during this year had a lasting impact, and that many of his novels show his first-hand knowledge of the people, places, and languages he encountered abroad.

A few years after returning to what would eventually become Canada, in 1856, James and a business partner opened a bookstore in Saint John. The bookstore helped establish James as an important member of the city’s cultural scene. It became a regular gathering place for local writers, artists, and visitors passing through.

But the costs of opening and running the shop piled up. Book sales just weren’t enough to cover the expenses. Eventually, the bookstore closed, leaving James with some debt and forcing him to leave for Nova Scotia in search of a fresh start.

In 1859, James De Mille married Elizabeth Anne Pryor. Elizabeth Anne was the daughter of Dr. John Pryor, the first president of Acadia College, where James’s father served on the board.

In 1860, James was appointed professor of classics at Acadia. By all accounts, he was a beloved and respected teacher and scholar.

While at Acadia, James helped introduce courses on classical history and promoted the study and use of Latin. He also taught Italian to a few interested students, sharing some of the rich cultural and scholarly experiences he had gained during his time abroad in Italy.

James published his first book in 1864. It was called Martyrs of the Catacombs and was set in Rome during the first century C.E.

In 1865, James resigned from his position at Acadia and moved to Halifax, where he had taken a job as professor of history and rhetoric at Dalhousie College. Because he was so highly regarded in Nova Scotia, he was offered the role of superintendent of education for the province, but he declined. Instead, he chose to continue teaching and writing.

James would live in Halifax for the rest of his life. While there, he continued to build his reputation as both a great teacher and a prolific author.

It’s not entirely clear why James wrote so feverishly and published so many books in such a short amount of time. Some have speculated that he was trying to pay off debts from his failed bookstore business. Others, less credibly, claimed he was paying off debts his father had accumulated. However, in letters written by one of James’s brothers after his death, the brother firmly shut down that idea. He said James had only given their father money once, and it had not been a significant amount.

Besides A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, some of James’s other works that people still find interesting today are his Brothers of the White Cross series, published between 1869 and 1873. These books were aimed at a young audience and were inspired by James’s own experiences growing up around the Minas Basin. They even reference real maritime events, like a major fire in Miramichi.

The Brothers of the White Cross books are exciting for young readers and lightly weave in themes like camaraderie, loyalty, and friendship without weighing down the adventure. They manage to impart some morals a little without dulling the fun, which is probably why they still hold up today.

You may already know this about how books were published back when James was writing, but for those who don’t: it was common for authors to release their novels in magazines as serials, publishing a chapter or two at a time over several weeks or months. If the story was well-received by readers, it would often be published later as a standalone book.

Because Canada’s printing infrastructure was very limited in the mid-1800s, Canadian authors often sent their manuscripts to printers in England to reach a wider audience there and in the U.S.

At first, I wasn’t sure why I included this part about serial publications and publishing abroad. I was about to cut it, but then I realized why it matters. It’s a reminder that in Canada, we have a long history of having to send our work outside the country to find success. We see it across all kinds of art and business. One of the most well-known, more modern examples is the Tragically Hip.

Even though they found some success south of the border, they were largely ignored by the American media, which some critics point out as a flaw. Part of me thinks it kind of sucks that we have to do that — appeal to people outside of Canada and depend on others to decide whether we’re successful or not.

And on the other hand, as much as I don’t like it, I think it’s pretty amazing when it’s done the right way. By that, I mean it’s awesome if we can share our Canadian voices with people across the globe, and they’re willing, curious, and interested in listening. I think that’s something to be proud of.

Still, there’s something about realizing that from the earliest days of Canada, we’ve often depended on outside recognition to validate a lot of our work.

This reminds me: the other day, I came across a stat that in 2024, only 12 percent of the books sold in Canadian bookstores were published by Canadian authors. I’m not an expert, and I haven’t studied the long-term data to know if that’s better or worse than usual, but my gut reaction was, “Oh man, that’s pretty low.”

It made me wonder whether, besides sending our best work abroad, maybe we’re also missing chances here at home to share and celebrate our ideas. Maybe we’ve gotten used to thinking that outside validation means success. Maybe we sometimes pull in ideas, voices, and products from outside because we assume they’re better, just because they come from elsewhere.

At the same time, I think it’s amazing that we can learn so much from the world around us. I’m definitely not saying we should only look inward or close ourselves off. That would be short-sighted.

I just think it’s worth asking sometimes: is what we create here just as good as what we bring in? Does the outside influence lift us up, or hold us back? Are we so focused on getting attention outside of Canada that we overlook what we have right here?

Anyway, getting back to James De Mille, it’s been said that you can sometimes detect a sense of his books being written in a rush. But it’s hard to know if that’s just hindsight, or if it comes from the fact that we now know he wrote so much in such a short amount of time.

If it is true, it might help explain why a lot of his works have been forgotten or are considered forgettable. But for all their flaws, he’s now celebrated for the humour and satire he wove into his writing.

Some have even compared him to Jonathan Swift, who came before him, and Mark Twain, who came after.

In biographies, De Mille’s biographers describe him as a joy to be around; extremely intelligent, but also creative, funny, and approachable. It seems he had a wide range of interests. He even worked on a special project for his four kids: translating and illustrating a version of Homer’s works for them to enjoy.

James also kept his love of languages alive throughout his life. He owned books printed in at least ten different languages, ranging from Sanskrit to Icelandic.

And for all his success academically and as a writer, it seems James didn’t take himself too seriously. He accepted the label some people placed on his books as “potboilers.”

His novels were fast-paced and usually mixed elements of romance, adventure, and a little bit of mystery. A potboiler is a creative work of questionable literary or artistic merit, the main purpose of which is to help the creator earn a living. The term comes from the idea of “boiling the pot,” meaning to provide for one’s daily needs.

Authors who produced potboilers were sometimes called hack writers or just hacks. Their works are often now called pulp fiction. But this doesn’t mean the works were bad. In fact, they were often really enjoyable and popular with wide audiences because they were accessible, not academic, and didn’t require readers to wade through heavy, complicated language.

By 1880, De Mille was fairly well known in the Maritimes, but also in the U.S. and Britain, as both an author and an academic. That year, Harvard University was even considering him for a high-ranking position. But sadly, James suddenly died in Halifax on January 28. He was only 46 years old.

His death left a big hole in his circle of friends and family, as well as in the broader community. In the years that followed, it seems he faded fairly quickly from public conversation and memory.

However, the once prolific author was about to re-emerge on the literary scene almost a decade after his death.

When De Mille passed away, he left behind stacks of paper filled with rough drafts and partial manuscripts with notes scrawled in their margins. As his family sorted through them, they stumbled upon one manuscript that, at least according to his brothers, had been known to them before his death.

According to one of James’s brothers, this particular manuscript was one of the first books James ever wrote. He had shown it to his brother many years earlier but had never been able to figure out how to end it.

That book was A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder.

De Mille’s family decided that A Strange Manuscript deserved the chance to be published, even though its author had passed away.

In 1888, the story was serialized by Harper and Brothers, listed as being written by an anonymous author. The book was well-received by readers. Even though it had been written nearly twenty years earlier, it featured themes that were right in step with the late 1880s fascination with exotic lost-world adventures, like H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines (1885) and She (1887).

Critical reception was mixed. Some critics accused the story of being unoriginal, calling it a cheap copy of newer lost-world adventures. However, once it came to light that A Strange Manuscript had been written close to two decades earlier by James De Mille, many critics retracted their complaints.

I find it interesting that De Mille’s work was seen as ahead of its time, even though it was published years after he had died. Today, A Strange Manuscript is believed to be one of the first, if not the first, Canadian science fiction novels.

Many critics now read it as satire, pointing out how it uses conventions that were familiar to earlier satirists.

And I don’t want this to turn into a full book review, but for context, I’ll give a quick rundown of the plot.

A Strange Manuscript opens with four British sailors aboard their yacht. They come across a tightly sealed copper cylinder floating in the sea. Inside, they find a manuscript written on papyrus.

Most of the novel follows the four men as they take turns reading the manuscript out loud, stopping occasionally to discuss and comment on what they’re hearing.

The manuscript itself is a first-person account by a fictional character named Adam Moore, an English sailor who became separated from his ship during an Antarctic voyage in 1844.

Moore stumbles into an unknown world where a race of people called the Kosekins live among strange beasts and dinosaur-like creatures. He works as an ethnographer for the Kosekins, learning their language, culture, and customs. He is helped along the way by a woman named Alma, who is also stranded there.

Through Adam’s eyes, the reader witnesses a series of bizarre events, including a baleful sacrifice, where Kosekin people eagerly volunteer to be slain, a hunt for a gigantic swamp creature, a flight on the back of a pterodactyl-like beast called an Athaleb.

The Kosekin society looks human but is completely alien in its values and customs. Moore describes them as a cult of death-worshippers who live in caverns and worship darkness. They are “kindly cannibals,” polite and generous, yet practicing ritual cannibalism, and they revere poverty, self-sacrifice, and death above all else.

In this upside-down world, all the typical values of Victorian civilization are reversed: wealth is shunned, light is feared, and death, whether by dying or killing, is considered the greatest joy.

Eventually, Adam Moore places the manuscript in a copper cylinder, tossing it into the sea in hopes that someone, somewhere, will find it and send word to his father and family to tell them what happened to him.

This brings the story full circle to the frame narrative aboard the yacht. The novel ends as the gentlemen on the yacht finish reading the incredible manuscript. Their reactions range from astonishment to skepticism. As they debate whether the story is true, the fate of Adam Moore and the Kosekins remains an open question when the tale concludes.

The slightly unresolved ending hints that De Mille may have intended a more elaborate conclusion but never got the chance to write it. Even so, the story still feels complete. Readers enjoyed it, and while many acknowledged that it ended a little abruptly, they didn’t feel like anything was missing.

You can imagine how enthralling this kind of story would have been at the time it was published. There were still huge parts of the world that were uncharted, undocumented, and largely unknown.

There was real excitement around exploring every corner of the earth and mapping it. It was still very much the age of colonial expansion, and nobody had reached the South Pole yet. No one really knew what was down there.

It’s easy to see why A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder would have captured so many imaginations.

While some readers enjoyed the adventure aspects of the story, others who saw it as more layered appreciated its satire and commentary on modern society. It gave readers a chance to reflect on life within a colonial and industrial world, to think more deeply about what it meant to be part of a colonial empire, and to question or call out the negative aspects of modern culture.

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder was published in book form later in 1888, after its serial run finished. But as time passed, James De Mille and A Strange Manuscript faded from collective memory.

It wasn’t widely talked about until the late 1960s, when a group of Canadian scholars and academics took an interest in recovering early Canadian texts. With the benefit of hindsight and a deeper understanding of the time in which it was written, A Strange Manuscript began to be more fully appreciated. Readers recognized its many layers of rich satire, and it gained recognition as one of the earliest examples of speculative fiction.

Speculative fiction takes place in a world that is either not Earth or a reimagined Earth with major differences in technology, history, or natural law, incorporating elements of invented history and lore that feel familiar in terms of society, culture, or history but are created from the author’s imagination.

It’s hard not to think that part of the intrigue surrounding A Strange Manuscript comes from the story of its own discovery.

The manuscript was drafted, tucked away among De Mille’s papers, and then forgotten for decades before being found by his family eight years after his death. The story of a lost manuscript surviving, and De Mille’s real-life manuscript surviving, seem to mirror each other.

These layers probably helped build its mystique and are part of why it’s celebrated today.

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder has since found its way onto university reading lists and is still discussed in modern literary circles and among those who study Canadian literature.

Which seems fitting, considering it was written by a professor who clearly had a love for both education and creative storytelling.

I’m sharing this story with you because I find it really interesting on a number of levels, but also because I don’t quite know how I feel about it.

On one hand, I’m saddened that De Mille never got to enjoy seeing its success, or benefit from it being published, talked about, and now studied.

On the other hand, for someone like me, who often feels anxious about not creating enough or not having time to finish everything I want to make, it leaves me hopeful. Maybe if you just create what you can, if it was meant to make it out into the world, it will find a way somehow.

And maybe things are meant to be talked about for a while, fade away, and then resurface again if they are still interesting and worth remembering.

I wonder what other works, whether in literature, art, or any creative field, are out there somewhere, tucked away in a forgotten corner, or stored on a hard drive or in the cloud, just waiting to be uncovered or resurfaced?

If De Mille died never knowing that one of his dusty drafts would outlive him, back when it took stacks of paper to hold a single story, imagine how many finished, almost-finished, or half-imagined works are sitting quietly right now, stored on tiny memory sticks or floating unseen in the cloud, just waiting to be found.

Story 2

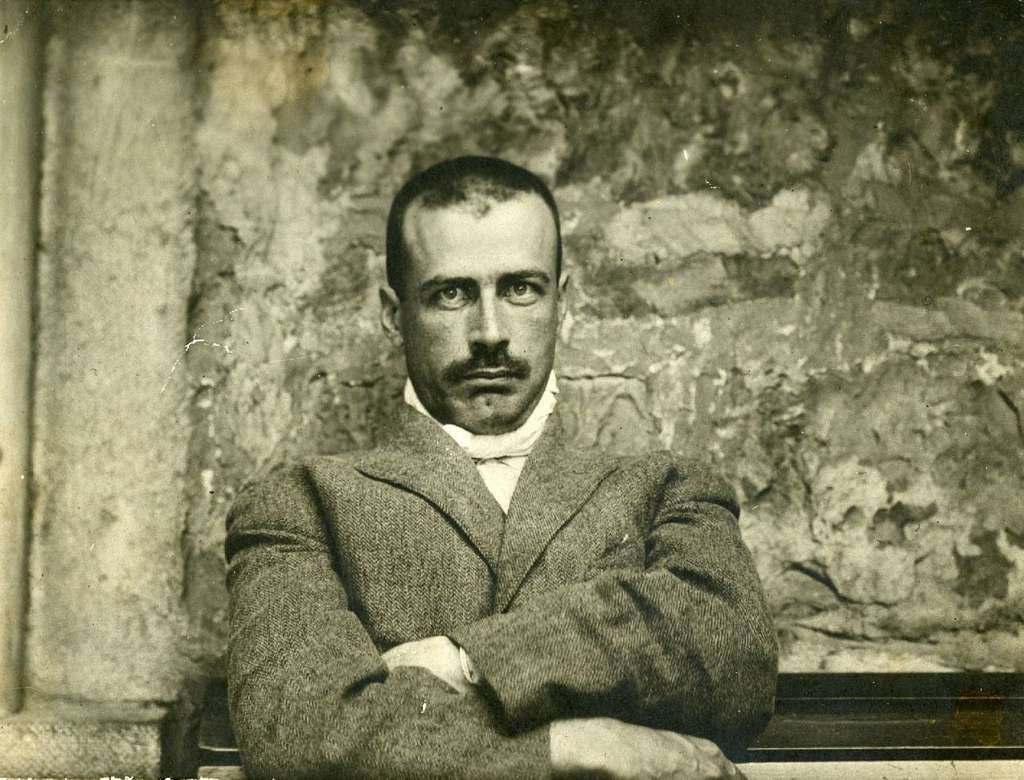

Our next story is about poetry that was, for a time, lost in a figurative sense, hidden in the rough drafts and increasingly erratic writings of a young French-Canadian poet named Émile Nelligan.

Émile’s verses were rescued by his friend and fellow poet Louis Dantin, who painstakingly combed through his handwritten drafts, editing, polishing, sharpening, and clarifying them to produce some of the most important Canadian symbolist poetry of the era, and maybe even of all time.

I’m a little embarrassed to admit I hadn’t heard of Émile Nelligan until recently. I chalk that up to one of two things: either I wasn’t paying close enough attention in school, or because Nelligan is French-Canadian, he simply doesn’t get talked about as much as he should in some English-speaking parts of the country.

To my French-Canadian readers and listeners, and to anyone else who already knows Nelligan’s story, I apologize. I realize this isn’t going to be an untold or lesser-known story for you. But if I’m right in my suspicion that it’s unknown to much of the country outside of Quebec, then I feel compelled to share it.

Émile Nelligan was born on December 24, 1879, to an Irish father and a French-Canadian mother. Those who knew him said he carried a blend of cultural influences. Some friends even said, “il sentait bouillir en lui le mélange de ces deux sangs,” meaning he “felt the boiling mix of two generous bloodlines.”

From his mother’s side, he absorbed the French Symbolist and Romantic traditions, drawing inspiration from poets like Paul Verlaine and Charles Baudelaire. His Irish roots gave him a more melancholic tone and a lyrical mysticism, both common threads in Irish literature.

It seems that Nelligan spent his entire life in Montreal, aside from a few summer vacations in Cacouna and one short sea voyage, of which not much is known about.

He attended the École Olier from 1886 to 1890, then Mont St. Louis from 1890 to 1893, and the Petit Séminaire de Montréal from 1893 to 1896. In September 1896, he enrolled at Collège Sainte-Marie but left in March 1897.

By the age of sixteen, Nelligan was publishing poetry in local journals, often under the pseudonym Émile Kovar, and impressing older writers with his talents.

He became friendly with Louis Dantin and Arthur de Bussières, and on February 10, 1897, he was inducted into the city’s literary society, the École Littéraire de Montréal. Those who knew him noticed both a persistent melancholy and a kind of premature maturity in his verses.

Nelligan’s early poems, written between 1896 and 1899, were exceptionally musical and rich with imagery. These were hallmarks of the symbolist movement—a style of poetry that aimed to evoke emotions and ideas through vivid symbols rather than direct statements.

He often recited his work at gatherings, standing tall with a grave but soulful voice. Many who heard him remarked on the musicality of his poetry, saying it made his verses both satisfying to listen to and hard to forget. Later critics would agree that the musical quality of his writing was one of its most remarkable features.

The themes he explored as a teenager were deeply personal. He wrote about childhood nostalgia, unrequited love, religious yearning, and a near-morbid fascination with madness and death. This inward focus set him apart from many of his Quebec contemporaries, who were still favouring patriotic or rural subjects in their poetry. Some scholars now point to Nelligan as the starting point of modern Quebec poetry, helping to liberate it into a more individualistic art form.

By 1899, the stylish young man had cultivated an image of a cursed poet. His dark hair and feverish black eyes left a striking impression on anyone who heard him speak. He was an avid reader and borrower of European literature, drawn especially to things like Gothic gargoyles, Etruscan urns, and Saxon knick-knacks.

While some critics argued he borrowed too much from his idols, others pointed to his incredibly passionate language and powerful use of symbolism.

On May 26, 1899, Émile Nelligan enjoyed a brief moment of public success that would go on to become part of Canadian literary legend. At a soiree at the École Littéraire, he recited a dramatic new poem he had written called La Romance du vin to a captivated audience. Eyewitnesses recalled the nineteen-year-old poet with his mane of hair flying, his eyes inflamed, and his voice resounding. When he finished, the hall erupted in delirious applause. It was pure rapture in the room. One newspaper reported, “Those vibrant verses provoked a frenzy of acclamations.” Nelligan had delivered what seemed like the crowning achievement of his young career, and for a moment, it felt like the entire literary world had noticed.

Unfortunately, this wildly successful moment would turn out to be Nelligan’s swan song. Shortly after the excesses of that night, he fell into a mental health crisis from which he would never fully emerge.

Friends had already noticed him growing more erratic and morose over the past few months. One account recalls how the poet would shut himself away for entire days, alone with his delirious thoughts, torturing his nerves and summoning ghosts. Émile told friends that he was visited by angry ghosts, phantom cats, and sinister demons that whispered despair to him. He had also begun suffering from nightmarish hallucinations. In one note, he wrote, “I have visions of blood-stained shadows, rigid beggars, cries of children, and rattling death groans.”

Each morning, he would scribble down recollections from his dreams in feverish verses that, while they sometimes showed flashes of genius, were also increasingly touched by madness. His behaviour at home had become volatile. He had fits of prolonged screaming, clashed often with his father, and was rude, dismissive, and demeaning toward his mother.

Many biographers believe Nelligan experienced some form of psychotic break during the summer of 1899, possibly schizophrenia. Sadly, Émile also struggled with suicidal thoughts and bouts of mania. In one of his more ominous poems, he wrote, “Je mourrai fou comme Baudelaire,” which means, “I will die mad like Baudelaire.” It would prove to be a prophecy that came painfully close to the truth.

On August 9, 1899, an exhausted, ill, and suffering Nelligan was taken to the Retrait Saint-Benoît, a psychiatric retreat run by the Brothers of Charity in East End Montreal, and committed there at the desperate insistence of his father. Before his twentieth birthday, he vanished from the literary scene, passing through the clanging iron gates into a world he would never leave.

There are not many records from the hospital from that era, but it appears he was diagnosed with insanity shortly after he was admitted. Long blank decades followed. Nelligan spent the next forty-two years in confinement, first at Saint-Benoît from 1899 to 1925, and later at the Saint-Jean-de-Dieu hospital from 1925 to 1941, until his death at age sixty-one.

His early years in the asylum were marked by silence, sedation, and the brutal psychiatric treatments of the time. Because records are sparse, we don’t know the full story, but it is widely speculated that he spent periods restrained in a straitjacket. There are even unconfirmed hints that doctors may have attempted a crude frontal lobotomy.

A hospital attendant named Brother Romulus later testified that they deliberately infected Nelligan with typhoid fever, hoping a high fever might cure his madness. It was a radical treatment that, at the time, some doctors genuinely believed in. According to Brother Romulus, after the fevers subsided, there was brief hope that Émile might be cured, but he soon relapsed. These were the desperate and crude measures of an era when schizophrenia had no effective treatment and was poorly understood.

Sadly, in the first few years after his committal, Nelligan also suffered from isolation. His mother, devastated by the events that led to his institutionalization, fell into a deep depression and couldn’t bring herself to visit him for three years. It seems she only ever visited once in all the decades he was confined. His father, who had pushed so adamantly for Émile to be admitted, largely disappears from the records and appears to have had little to do with him afterward.

Only a few loyal friends from his literary circle, like Louis Dantin, Germain Beaulieu, and Dr. Ernest Choquet, made the effort to visit Nelligan in the asylum. Passing through the cold institutional hallways, they found a young man profoundly withdrawn, sunk deep into his interior world.

During those first few years of seclusion, Émile spent hours writing, but the work was incoherent and rambling — largely undecipherable verses and what looked like gibberish. People who encountered Nelligan during those days said he often seemed half-asleep, lost in a vegetative state, distant and detached from reality. The creative spark that had once made him brilliant seemed to have gone out.

This is where Louis Dantin, Émile’s friend and fellow poet, plays a larger part in the story. Dantin, whose real name was Eugène Seers, made sure that Nelligan’s genius would not be forgotten. He had recognized Émile’s talent early on and took it upon himself to polish the rough edges of his early work, serving as an editor, advisor, and guide, helping him clarify and shape his ideas. People who observed them working together often credited Dantin with helping the teenager turn his bursts of inspiration into carefully crafted lines with tight rhymes and strong attention to form.

After Nelligan was committed to the asylum, his parents gathered up all the manuscripts and notebooks he had left behind and passed them to Louis Dantin. Dantin then took on the task of assembling them into a book, starting in 1902. He dedicated hours to compiling 107 poems written by Nelligan between 1896 and 1899, ordering and preparing them for publication.

It is worth noting that Dantin’s role was not just to proofread and organize Nelligan’s work. He also made editorial decisions that helped shape how the world would come to see him. Dantin corrected obvious errors and chose to remove fragmented or incoherent sections, especially some of the later, more surreal verses that reflected Nelligan’s hallucinations and struggles with madness.

In September 1902, while still working on compiling the book, Dantin published a long critical essay titled Émile Nelligan est mort (“Émile Nelligan is dead”) in the Montreal journal Les Débats. The dramatic title referred to the poet’s creative death, even though he still lived on, physically, in the asylum. The essay helped to build the myth of Nelligan as a tragic genius who burned too brightly and quickly burned out.

In the essay, Dantin wrote, “Neurosis, that wild divinity which grants death along with genius, has consumed everything, carried everything away.” He compared Nelligan to a moth singeing its wings or a butterfly burning itself in the flame of its own dreams.

This important essay was included as a preface in the book of Nelligan’s poetry.

One of the things that drew me to this story was the romantic portrayal of the thin line between creativity and madness, the same idea Dantin referenced in his essay. I’m sure we’ve all heard stories about artists, musicians, or writers who seemed to teeter between creative genius and insanity. It’s a theme that has been explored again and again in books, movies, and other portrayals of figures like Nelligan, described as tragically brilliant.

Sometimes, it seems that the parts of our brain that allow us to access such powerful, brilliant ideas are also the same pathways that can lead to things like mania or other mental health struggles. I mention this not to perpetuate stereotypes or harmful myths that are not grounded in science. I mention it because this idea has come up again and again throughout history. I am not sure if science has ever firmly established a link, or if it is just an anecdotal pattern we notice in a small number of people who, sadly, suffer from mental illness while also being tremendously creative.

Getting back to Dantin’s essay, he didn’t just praise his friend’s work; he was also critical of it. He didn’t shy away from highlighting its weaknesses. He pointed out where Nelligan had borrowed, perhaps too closely, from his French idols. Like other critics, he would have preferred that Nelligan draw more inspiration from local Canadian sources. Still, for all its flaws, Dantin argued that Nelligan’s poetry was even more remarkable because of the way it overcame its weaknesses.

In early 1904, the first edition of Émile Nelligan et son œuvre was published, five years after he had been committed to the asylum. It was printed by Beauchemin in Montreal, which mattered because the Canadian publishing industry was still in its early stages.

Something strange about that first edition is that Nelligan was not named as the author on the cover. Instead, Louis Dantin was listed, and the book appeared more like a critical study completed by Dantin on Nelligan’s poems.

It’s easy to speculate and jump to conclusions, thinking there might have been something nefarious going on, or that Dantin was trying to take credit for Nelligan’s work. But some historians have pointed out a simpler explanation. Because Nelligan was living in an asylum and was legally deemed incapable of making his own decisions, therefore he could not give consent or be seen as consenting to the publication of his poems. Listing Dantin as the author might have been more of a logistical necessity than anything else. Later editions of the book would clearly name Nelligan as the true author.

The first publication of the poems in 1904 met with immediate critical acclaim in Quebec and abroad. People were amazed by the emergence of such talent from Canada, a place not yet known for Symbolist poetry. Even influential critics in France hailed Nelligan’s work as original and brilliant, writing things like, “There are depths in Nelligan’s work to which Canada had not yet been accustomed.”

Like Dantin, some critics pointed out that Nelligan’s poetry lacked a local Canadian flavour. But that criticism was often countered by praise for his remarkable ability to channel the spirit of the French Symbolists at such a young age. In a time when so much attention was placed on writing about Canadian themes and conventions, Nelligan’s refusal to conform made his achievements even more impressive.

At home in Montreal, Nelligan’s work quickly attained classic status. Fellow poets who had known him heaped praise on the book.

Over the next two decades, the myth of Nelligan continued to grow. In 1918, writer Robert de Roquebrune published an influential essay describing Nelligan as a “heroic and sacred figure,” the very essence of adolescence, and an archangel standing at the gates of a paradise of beauty. Roquebrune also described a double-sided destiny in Nelligan, suggesting he was predestined for both art and madness, his extreme creativity mirrored by extreme suffering.

By 1922, critics like Marcel Dugas praised Nelligan as the pioneer who had birthed pure individualist poetry in Quebec, where the tradition had traditionally focused on collective themes.

Nelligan’s fame even crossed language barriers. By 1924, he was cited in an English-language Canadian literature textbook, and by 1930, he was recognized as a poet of the first order across broader Canadian circles.

Ironically, all this admiration was for a man who was still alive, pacing the grounds of an institution, completely unaware of his growing fame.

As Nelligan gained more acclaim and notoriety, more people became interested in meeting the man behind such an important contribution to Canadian literature and the Quebec poetry scene. He began receiving visitors — young aspiring poets, students, and journalists — who were curious to see how he was doing.

This attention may have stirred something in Nelligan during his final years. Although he had never truly stopped writing, most of what he produced by then was largely undecipherable, accessible only to himself. Within six notebooks and various scraps of paper he had compiled while in the asylum. It seems he occasionally tried to rewrite or revise earlier poems from memory.

Some accounts suggest he tried adding new verses here and there. Other witnesses recalled that Nelligan could still recite his old poems by heart, sometimes with astonishing accuracy, even decades after he had first written them and despite everything he had endured. Visitors often begged him to perform his most famous piece, La Vaisseau d’Or (“The Golden Ship”), and he would oblige, reciting it in a low, monotone voice. His eyes were vacant, but his memory remained remarkably intact.

In 1939, a young poet named Léo Bonneville spent an hour with Nelligan and later recounted how the frail sixty-year-old, wearing a threadbare suit, suddenly stood and began to recite La Vaisseau d’Or. He spoke slowly, without hesitation, in a grave voice, his thin hands trembling slightly. Bonneville wrote that Nelligan then softly recited Romance du vin in full when Bonneville requested it too.

After the performance, Nelligan confessed that he could no longer write new poetry because inspiration no longer came to him. Yet he added, with a sad pride, “My poetry, I have carried it with me. I have carried it in me forever.”

Nelligan’s story is fascinating and tragic. One part always sticks with me: the human mind is an incredible machine sometimes. Stories like this remind me that we still know very little about how the brain works, or sometimes, how it does not.

Somewhere in that foggy mind, Émile could still find the neural pathway to access those old files where his creativity had stored his early poems. It reminds me of studies and anecdotes about dementia patients who, even after losing so much of their memory, can sometimes miraculously recall music or songs when little else remains.

There is some kind of magic in music, and in poetry that reads like music, like Nelligan’s did. It seems to be a universal language that our human brains are somehow pre-wired to understand, even when many other things are lost.

It is both beautiful and sad. But I also find it gives me hope that maybe one day, that mysterious connection will help unlock treatments for the terrible effects of Alzheimer’s, dementia, and other mental health and cognitive challenges.

A more recent development in the study of Nelligan’s asylum notebooks is that some analysts have found what they believe is a method in the madness. Through deep study, pattern recognition, and analysis, it appears that Nelligan’s wordplay and cryptic allusions in his later writings may hint at a private language, or idiolect, through which he was still striving for poetic expression, even if it was unrecognizable to others.

This idea excites me, especially when I think about the possibilities of using AI for pattern recognition. Maybe we are getting closer to using machine learning to uncover hidden communication systems. People might still be trying to communicate, even if they cannot use words we immediately understand. Machines could help detect the patterns and repetitions that show someone is still expressing coherent thoughts. Then it would be up to us to figure out how to decode and respond to that communication.

While there is hope for the future, these kinds of advancements came too late for Nelligan. He never had the chance to benefit from them.

It seems he was painfully aware of his situation. Some visitors later recalled that in 1937, when a reporter told Nelligan how highly regarded he had become, he simply replied, “Moi aussi je suis mort depuis 25 ans,” which means, “Me too, I have been dead for 25 years.” Speaking metaphorically, he seemed to see himself as already dead to the world, at least creatively.

In a way, it fulfilled the tragic idea that Dantin had put forward back in 1902, when he said the death of Nelligan’s genius was the death that truly mattered.

Nelligan’s actual death came a few years later, on November 18, 1941.

After his death, new editions of Nelligan’s work continued to appear. In 1945, a fourth edition of his book of poems was released, the first one to fully credit Nelligan as the author. In 1952, a “complete edition” edited by Luc Lacourcière was published, adding fifty-six more poems that had been left out of Dantin’s original selection. These included youthful pieces published in newspapers under pseudonyms, and possibly some recovered drafts.

This fuller picture only enhanced Nelligan’s stature in the late twentieth century. Scholars later brought his asylum writings to light, publishing facsimiles of his hospital notebooks and autograph manuscripts in the 1990s.

Émile Nelligan had become a cultural icon in Quebec — the subject of songs, stage plays, a feature film, and even an opera. Critics, writers, and filmmakers have commemorated his genius, his madness, and his martyrdom. His name now carries the aura of a poet and seer, a figure sacrificed by fate, a romantic myth that still fascinates people.

Yet behind the myth lies the very real story of a young man whose voice was rescued from oblivion by a friend’s devotion. The contrast between Nelligan’s polished early verses and the raw jottings from his asylum notebooks is stark and heartbreaking.

In one of his best love sonnets, Le Vaisseau d’or (“The Golden Ship”), the poet hauntingly imagines his heart as a magnificent golden ship wrecked in a treacherous sea. He asks, “What is left of it? What became of my heart, that deserted ship? Alas, it has sunk into the abyss of dream.”

These lines, written at the age of nineteen, proved eerily prophetic for Nelligan’s life. His ship, his mind, and his talent did strike the reef of insanity and sink into darkness.

But thanks to Louis Dantin’s editorial lifeline, Émile Nelligan’s words did not sink with them. They floated free of that abyss, illuminating over a century of readers with their music and anguish.

The asylum notebooks, having been recovered and studied, now speak to us. They allow us to see Nelligan both in his youthful exuberance and in his twilight mutterings. His story is profound and will live on in the history of French-Canadian literature and Canadian literature as a whole.

Story 3

Our third story is about a book that was lost. Unlike James De Mille’s novel, this one was published while its author, Agnes Deans Cameron, was still alive, and she was able to enjoy its success, at least for a few years before she died. Unlike Émile Nelligan, whose creative death and later physical death added to his allure, it seems this author’s passing had the opposite effect. When she died, her book quietly faded away.

Agnes had been its biggest promoter. After her death, it appears no one stepped in to keep the conversation going. The book was called The New North: Being Some Account of a Woman’s Journey Through Canada to the Arctic. It captured her incredible paddling journey to the Arctic, a feat that earned her the distinction of being the first white (European-descended) woman to do so. This makes it even more remarkable that both she and her book were forgotten so easily, and for so long.

Agnes Deans Cameron was born on December 20, 1863, in Victoria, British Columbia, which at the time was still the Colony of Vancouver Island. Her parents, Duncan and Jessie, were Scottish immigrants. Like most girls of the era, she was expected to marry, have children, and run a household. But Agnes had other plans. She forged an extraordinary career that was anything but conventional.

By all accounts, Agnes was an outstanding student throughout her school years. When she was just sixteen, while still attending Victoria High School, she wrote and passed the teacher’s exam. It earned her a certificate that allowed her to teach anywhere in British Columbia.

Cameron quickly rose through the ranks of Victoria’s school system, becoming the city’s first female high school teacher and, in 1894, its first female principal at South Park School. She was known as an excellent teacher and an outspoken advocate for women’s equality in the profession.

She actively supported causes like women’s suffrage, pay equity, and ending age discrimination, arguing that women had the same “right to help in determining what laws shall govern” society. In 1906, she served as president of the Dominion Educational Association and helped lead teachers’ institutes, using these platforms to demand equal status for women in education. Her efforts helped establish her as a leader, and she was well-liked by fellow teachers, parents, students, and much of the broader community.

While it was becoming more common for women to enter teaching near the end of the 1800s, it was still unusual for women to rise through the conservative, patriarchal British Columbia public school system. As you can imagine, Cameron’s advocacy led to several high-profile clashes with educational authorities. Her actions were scrutinized publicly as officials tried to discredit her.

In 1901, she and another female principal were suspended for “insubordination” after resisting a new policy that replaced written exams with oral ones. The other principal apologized and was reinstated quickly, but Cameron stuck to her guns. Thanks to the strong support she had earned from the community, public pressure forced the school board to reinstate her.

However a more serious conflict in 1905 ended her career. She and her school’s art teacher were accused (unfairly, in her view) of allowing students to cheat by permitting the use of rulers during a freehand drawing exam. Cameron denied any wrongdoing, and the public uproar over her dismissal prompted a formal inquiry. She even ran for a seat on the school board and won the most votes in the 1906 trustee election. Nevertheless, a royal commission ruled against her, and her teaching certificate was suspended for three years, effectively ending her career in education.

At 42, Cameron found herself without a job in the field she had devoted more than two decades to. But she landed on her feet, pivoting to a new career as a writer and journalist. She joined the newly formed Canadian Women’s Press Club, an important network of professional women writers founded in 1904 by pioneers like Kit Coleman and Robertine Barry. Through these connections, Cameron quickly landed a commission with the Western Canada Immigration Association in Chicago. Her assignment was to use popular media to attract settlers from the United States and Eastern Canada to the Canadian West.

This job set the stage for the greatest adventure of her life. Cameron planned to make an unprecedented journey from Chicago, “across the Belt of Wheat and the Belt of Fur,” to the Arctic Ocean, and then publish her experiences to inspire immigration.

In 1908, accompanied by her 20-year-old niece, Jessie Brown Cameron, and her trusty portable typewriter, Cameron set off on a 10,000-mile expedition through some of the most remote parts of Northern Canada. Over six months, they travelled by train from Chicago to the end of the steel at Edmonton, by stagecoach to the railhead at Athabasca Landing, then by river using Hudson’s Bay Company flat-bottom boats–big square wooden rafts piled high with supplies. They journeyed down the Athabasca and Slave Rivers, crossed Great Slave Lake, and followed the Mackenzie River to its delta on the Arctic coast. There, the river gracefully merged into icy, gray waters under a pale sun. In doing so, Cameron and her niece became the first white women known to reach the Arctic Ocean over land in Canada.

During their incredible journey, Cameron took copious notes on her portable typewriter, hauling it with her on riverboats and portages all the way to the Arctic and back. She also snapped dozens of photographs using her Kodak camera.

On the way home, Cameron and her niece traveled through the Peace River region, where golden fields stretched to the horizon. Cameron shot a moose there and later joined the first steamship voyage on Great Slave Lake.

It is often implied by labels like “first white woman” or “first European” to make the journey, but I think it is important to say the obvious out loud. Of course, Cameron was not the first woman to reach the Arctic. Indigenous women had been making these journeys long before Europeans even arrived. Nevertheless, Cameron’s expedition was a major accomplishment and a significant success in its own right.

After returning home, Agnes capitalized on her newfound fame. She spent much of late 1908 and 1909 giving lectures across Canada and the United States, captivating audiences with illustrated “magic lantern” (a heavy, brass-and-wood contraption that projected ghostly light through glass slides) shows. She developed a set of popular lectures with titles like “Wheat, the Wizard of the North,” “From Wheat to Whales,” and “The Witchery of the Peace,” using vivid photographs and detailed notes she had taken along the route.

These talks presented an enticing vision of Canada’s fertile prairies and resource-rich frontiers to crowds of would-be immigrants. Cameron’s lecture tour packed halls in the American Midwest and as far east as Toronto, where members of the social elite clamoured to shake her hand after presentations.

Between lectures, Cameron also worked on chronicling her expedition in a book she would go on to publish in 1910, titled The New North: Being Some Account of a Woman’s Journey Through Canada to the Arctic. That same trusty typewriter that accompanied her on the journey was used to type up the manuscript, which she then sent to a respected publishing firm called D. Appleton and Company. They published her 390-page travel log in New York and London. The book included many of the photographs Cameron had taken and used in her lectures, along with several illustrations she had created during and after the expedition.

As a travel narrative, The New North combined adventure with purpose. Its central theme was to introduce readers to the vast, little-known region of northwestern Canada and to dispel myths about it being an uninhabitable wasteland. Cameron portrayed the North as a place of great promise, which is why she chose the optimistic title. Her writing was vivid and witty, and she took great care to describe the sweeping wheat fields of the prairies, the booming railway towns, and the natural riches of the northern wilderness.

One recurring theme in Cameron’s writing is the abundance of resources she observed along her trek. She was especially enthusiastic about the Athabasca oil sands in Alberta, where she saw tar and oil seeping along the riverbanks. She even visited an early oil drilling site run by a pioneer entrepreneur and reported on the attempt to tap what she called “elephant pools of oil” beneath the Athabasca. In hindsight, her observations are remarkable, given the importance of the oil sands a century later.

In her book, she also worked to dispel the myth of the North as a perpetually frozen, hostile environment. She made a point of highlighting the summer growth and agricultural development she encountered in the northern regions. At the same time, she wrote as a keen observer, documenting the customs of the Indigenous peoples she met, including the Cree, Chippewa, and Inuit, as well as the daily realities of traders, missionaries, Mounties, and homesteaders.

Modern scholars note that Cameron was a perceptive observer of the Indigenous communities and women she encountered, although her perspective was still that of a colonial traveller of her era.

Some critics have pointed out that The New North reflects an “imperialistic mode” and a “missionary zeal” consistent with Cameron’s aim to celebrate Canada’s northern expansion. She often described the landscape as a new frontier for Anglo-Canadian progress and sometimes portrayed Indigenous people with a paternalistic sympathy, comparing their needs to those of “children” who could benefit from schools and churches. These views were, unfortunately, common in 1910, especially given Cameron’s social activism around causes like education. Her writing reflects both the attitudes and the compassion of a woman very much shaped by the Canadian settler society she came from.

Even so, she conveyed genuine admiration for the endurance and skills of the northern peoples and often acknowledged the hospitality and guidance she received from Indigenous guides throughout her journey.

Another notable theme in The New North is women’s capability and independence. By simply undertaking and writing about such an arduous expedition, Cameron challenged gender norms. She did not focus heavily on feminist arguments in the book itself, but her presence north of the 53rd parallel, carrying a rifle, a camera, and a typewriter, sent a powerful message all the same. She also described the day-to-day challenges of wilderness travel, from clouds of mosquitoes to physically demanding portages to freezing weather on Great Slave Lake, showing the physical toughness the journey required.

But the book is not all business. Cameron writes engagingly and infuses her descriptions of the North with humour and human-interest stories. Sometimes, her writing becomes poetic, especially when describing the beauty of the Northern Lights or the long sunshine of summer in the land of the midnight sun. For the most part, though, the book remains rooted in journalism.

The charismatic school teacher turned explorer had become a media sensation by 1910 following the success of The New North. The book made its way onto bestseller lists, and press coverage often focused on the fact that it was an account of a woman’s journey. Cameron had anticipated this kind of reaction and hoped to leverage the era’s fascination with lady travellers. Her achievement was frequently compared to those of male explorers, with some even calling her the “female Marco Polo” of Canada.

The Canadian government was thrilled with the success of Cameron’s journey, lecture series, and book, and sent her to Britain for two years to continue promoting Western Canada to prospective immigrants between 1910 and 1912.

While in London, she was welcomed into the Institute of Journalists and spoke at venues like Oxford, Cambridge, St. Andrews, and the Royal Geographical Society, spreading the gospel of Canada’s “new North.” At the end of 1911, Cameron returned to Victoria to a hero’s welcome. The City Council even held a public reception in her honour. Cameron, who had travelled up toward the top of the world and become famous for it, was now “on top of the world” in terms of her celebrity status.

Timing must have felt like everything for Cameron. Just a few years earlier, she had been forced out of teaching, and instead of retreating from the public eye and fading away, she emerged as one of Canada’s most famous writers at a time when the country was hungry for its own stories and heroines. Her voice, as a Western Canadian woman offering first-hand insight into the far North, was both timely and unique in the literary landscape of 1910.

I can’t help but wonder if the school board members who despised her and pushed her out of teaching ever begrudgingly read her book or sat through one of her lectures. Regardless, she definitely got the last laugh.

In terms of timing, remember that this was just over ten years after the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898, which had spawned works like Jack London’s Call of the Wild in 1903 and the poems of Robert W. Service. There was a growing appetite for tales of adventure and travel in the Canadian North and West.

Another woman travel writer who had achieved a high degree of success was Mina Benson Hubbard. She wrote A Woman’s Way Through Unknown Labrador in 1908 and captivated audiences on the East Coast, in Britain, and in the United States with her story of how she finished her late husband’s mission to map Labrador. Hubbard deserves her own Pinecone Diaries story, but if you can’t wait for that, I suggest looking her up. She also lectured in Britain about her expedition, during which she mapped the Nascaupee and George River systems and became the first white (European-descended) woman to travel and explore the remote regions of Labrador.

Women like Hubbard and Cameron seemed unstoppable. But that is where Cameron’s story takes a tragic turn. Just a few months after returning from her whirlwind lecture tour overseas, in May 1912, Agnes Deans Cameron died at age 48 from complications of appendicitis and pneumonia. Her death was devastating to her fans in Canada and abroad. For many, it felt like the loss of a hero and an icon. People had been so excited to see what she would do next that her sudden death left them in shock.

In the decades that followed, The New North gradually faded from public view. Eventually, it went out of print, and by the mid-20th century, the book was nearly impossible to get your hands on. It survived mostly as a reference for historians or sat buried in dusty library stacks. Cameron’s untimely death was likely the main reason the book fell out of favour. When she was alive and promoting it, people flocked to hear her speak and to buy it. But without her, the nation and the world seemed to move on.

Just when it seemed like her story might fade away completely, things began to change. By the late 1900s, interest in women’s history and pioneer accounts started to surge, and with it, Agnes Deans Cameron’s remarkable story began to resurface.

After more than 70 years, The New North was resurrected in a revised edition in 1986. This revival was led by scholar D.R. Richeson, who edited a new version of Cameron’s travelogue. The 1986 edition, titled The New North: An Account of a Woman’s 1908 Journey Through Canada to the Arctic, was published in Saskatoon and simultaneously by the University of Nebraska Press. Richeson provided an introduction and annotations, placing Cameron’s work in historical context for modern readers who might not have known her story. This effort was part of a broader wave in the 1980s to recover and celebrate the narratives of women explorers. The new edition made Cameron’s book accessible again, complete with her original photographs and illustrations, helping to preserve her legacy as a significant Canadian travel writer and offering contemporary audiences a woman’s perspective on early 20th-century northern Canada.

During this revival, it was also noted that Cameron had been one of the first celebrated authors born in British Columbia and had achieved world renown by 1910. There was a growing sense that such an influential figure should not be forgotten.

Today, Agnes Deans Cameron and The New North are studied and celebrated as important parts of Canadian history and literature. After being largely forgotten for most of the 20th century, historians and literary critics now recognize her as an influential early feminist and a visionary advocate for Western Canada. In 2017, during Canada’s 150th anniversary, Cameron was officially named one of the 150 most significant individuals in British Columbia’s history. As one BC publication noted, “precious few people know much about her,” but efforts by scholars and writers continue to change that. In 2018, a full biography titled Against the Current: The Remarkable Life of Agnes Deans Cameron by Kathy Converse was published, offering a detailed portrait of Cameron’s remarkable life.

Academic critique of The New North has also deepened over time. Modern scholars examine the book not only for its content but also for what it reveals about the mindset of its era in literary and cultural studies. Cameron’s narrative is often discussed through the lenses of post-colonial and feminist analysis. Scholars continue to explore how her work both reinforced and subtly challenged the imperial narratives of her time.

On one hand, she can be seen as furthering the colonial project by encouraging settlers to occupy Indigenous lands. On the other hand, her acknowledgment of Indigenous guides and her critique of cruelty and injustice she witnessed show a measure of sympathy that was not universal among imperial writers back then. Her work is also valued by environmental historians for its detailed descriptions of the environment and natural resources of the West and North at the time.

Because she died so soon after becoming a journalist, it is easy to forget that she helped open the door for many generations of women journalists in Canada who followed her.

As the Royal BC Museum noted, Cameron was an “international celebrity” in her day, and her name deserves to be inscribed in our history. The New North has now entered the public domain and is available for free on Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive. It has also been digitized for modern readers who prefer e-readers over physical books.

I have to admit that my first assumption about why her book fell out of print and was forgotten for so long had to do with the fact that she was a woman. But I was wrong. It is clear that she was celebrated precisely because she was a woman, and that was true not only in her hometown of Victoria but also across Canada, down into the United States, and even overseas in Britain. Her funeral was reportedly the largest Victoria had ever seen. The local newspaper, The Daily Colonist, eulogized her as “possibly the most remarkable woman citizen of the province.”

When you place her story beside that of James De Mille, a prolific author from a few decades earlier who was also largely forgotten for a long time, and who was a man, the picture becomes clearer. I think now that the main reason both Cameron and De Mille faded from public memory was because they died so young and so abruptly. They did not have the chance to fully enjoy the success of their work or continue promoting it, either by speaking about their books or by writing more.

We have seen this pattern play out many times: fame, then being forgotten, and later being found again. It makes me wonder which authors and works we celebrate today might one day be forgotten after the authors pass away. Will they be revived? And if so, under what circumstances? What will books even look like fifty, seventy, or a hundred years from now?

It is an interesting thought, although a little morbid if you sit with it too long. Instead, I encourage you to enjoy the great, important, unique, and interesting work available to us today from so many amazing authors across Canada. They represent different regions, cultures, genders, and abilities. And I encourage you to keep an eye out for the lesser-known or hidden authors whose work is still waiting to be rediscovered, or maybe even discovered for the first time.

Thanks for reading, please let me know what you think of this new format. Or share your thoughts on any of the authors and their books we discussed.

And then, have a rad rest of your day!

Sources to be posted shorty…

Share this post