The Scholar Who Saw Hitler Coming

From Halifax to Berlin: The extraordinary story of Winthrop Pickard Bell, the Canadian academic-turned-spy who predicted the rise of Nazi Germany

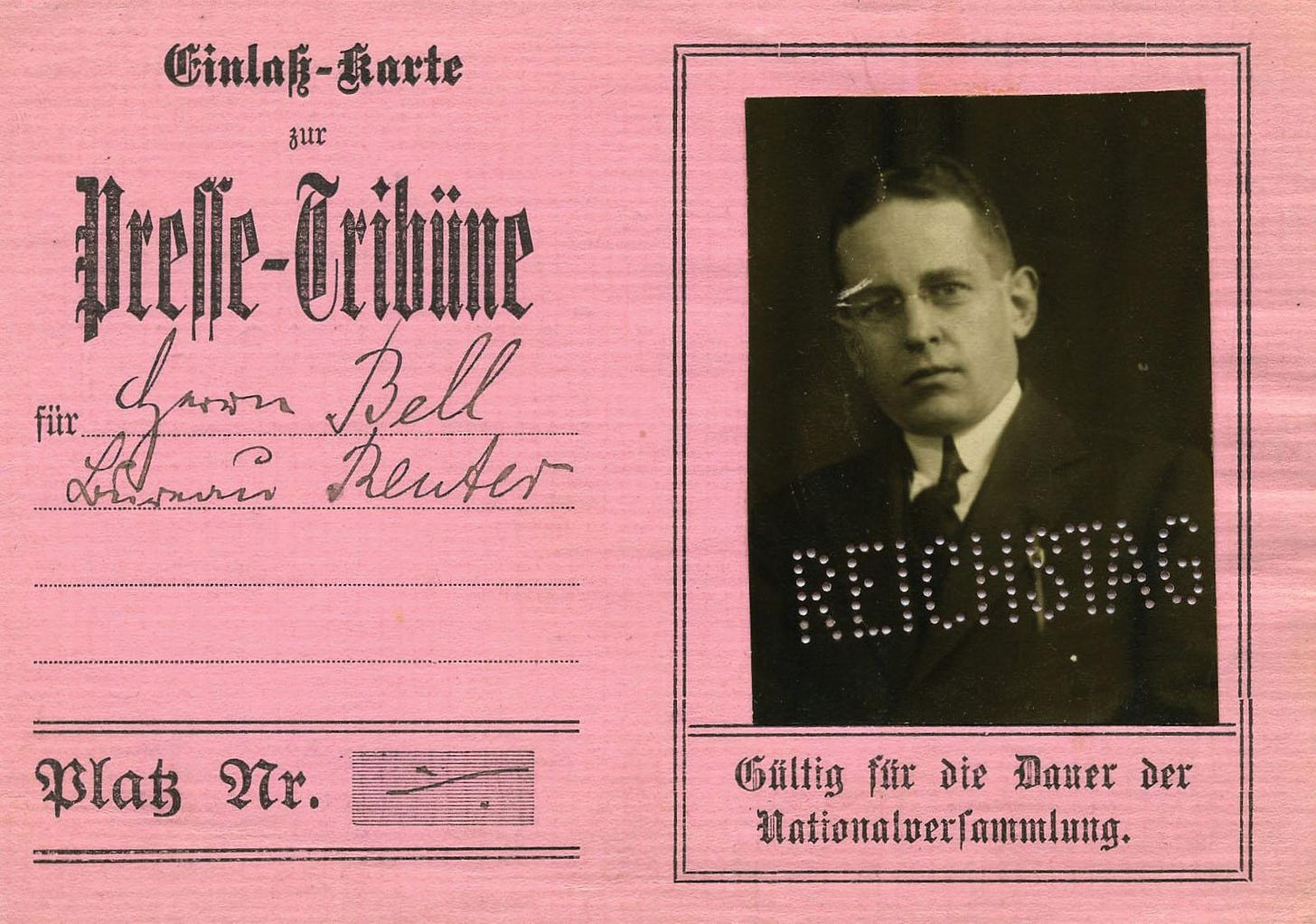

Berlin, 1919. In a dark, cigarette smoke-filled café near the Spree River, a mild-mannered Canadian sat quietly at his corner table, his wire-rimmed glasses fogging slightly from the steam rising from his coffee cup. To casual observers, he was just another foreign correspondent scribbling in his notebook—perhaps jotting down details about Germany's post-war struggles for the Reuters news agency.

But Winthrop Pickard Bell's carefully coded notes told a far darker story.

Through the café's grimy windows, he watched as gaunt children picked through garbage bins for scraps of food—casualties of the Allied blockade that had brought Germany to its knees. Inside, hushed conversations in rapid-fire German swirled around him, filled with anger and desperation. After four years in a German internment camp,

Bell understood every word, and what he heard chilled him: whispers of revenge, of military plots, of blame directed at Jewish citizens.

His hands trembled slightly as he wrote, not from fear, but from the urgent need to make his Allied handlers understand what he was witnessing. This Canadian philosopher-turned-spy was seeing the seeds of catastrophe being sown in real-time. In his dispatches, he would warn of a coming storm that few could imagine—a darkness that would engulf Europe two decades later.

For this unsung hero from Halifax, Nova Scotia, the signs were unmistakable. But would anyone listen to a Canadian academic's warnings about Germany's future?

This is the story of Winthrop Pickard Bell—scholar, spy, and perhaps one of the first people in the world to predict the Holocaust. His warnings about Germany after World War I might have changed world history, if only someone had paid attention.

Winthrop Pickard Bell was born in Halifax, NS on May 12, 1884. He came from a family closely connected to Mount Allison University—his grandfather was the institution’s first president, and his brother Ralph later became its first chancellor. You might think that would be enough for Bell to stay on a typical academic path, but his life was anything but ordinary.

Bell’s early years were a whirlwind of education. He earned degrees in Mathematics (BA, 1904; MA, 1907) from Mount Allison, took engineering courses at McGill University, and then studied at Harvard, where he completed a master’s in Philosophy in 1909.

The real turning point, though, came around 1910, when he decided to head overseas. Later that year he made his way to Germany, where he began studying under the famous philosopher Edmund Husserl at the universities of Leipzig and Göttingen. By 1914, he’d earned a PhD in philosophy—a huge milestone for a Canadian student of his era.

The timing of Bell’s German education wasn’t the greatest as tensions were mounting there and across Europe in the lead-up to World War I. Undeterred and largely unconcerned with the military conflicts and political tensions, Bell went to Germany purely for academic pursuits, fascinated by the cutting-edge philosophical work German academics were engaged in.

But when war broke out in August 1914, he suddenly became an enemy citizen on German soil. Within weeks, he was arrested and sent to Ruhleben Internment Camp, an old horse-racing track outside Berlin.

Bell spent 1914–1918 locked up in Ruhleben, along with other foreign civilians stuck in Germany at the start of the war. It might sound strange, but this grim experience turned him into the perfect intelligence asset. You see, while living in that camp, Bell became even more fluent in German and got a front-row seat to the desperation caused by the Allied food blockade. Civilians were starving, the economy was in shambles, and political tensions were running high.

If you’re unfamiliar with the food blockade, it was a strategic starvation campaign that Allied naval forces engaged in between 1914 and 1919 that crippled Germany’s civilian population. During this period, the Allies, led by Britain used their navies to restrict all imports to Germany, including food, fertilizers, and industrial materials. This was done to weaken Germany’s war efforts and is estimated to have caused the death of at least 500,000 civilians.

Bell recognized how this widespread suffering was fostering a dangerous resentment among the German population. His fluent German allowed him to understand the angry whispers of guards and visitors—whispers that would later prove prophetic.

Bell’s time in Ruhleben during the wae had forged a personal resilience and an understanding of German culture that most Canadians or Brits simply didn’t have.

German authorities, suspicious of him from the start, had unknowingly handed him the tools that would later define his covert work. By the time he was released in 1918, Bell had been immersed in the language, the mindset, and the dire circumstances of post-war German society.

Right after the Armistice, his name landed on the radar of Prime Minister Robert Borden and British intelligence chiefs. They knew he was back in Canada, they knew he had the language skills, and they sensed he was someone who could blend in abroad.

In 1919, Bell was recruited by MI6 as a spy and bankrolled in part by Canadian funds.

He then slipped back to Germany under the guise of a Reuters reporter. Imagine a mild-mannered scholar, who also happened to hold a Harvard degree, wandering through the chaotic streets of post-war Berlin and beyond—sending carefully coded covert intelligence reports to Allied leaders. That was Winthrop Bell, a Canadian philosopher turned undercover operative.

His dispatches were startlingly detailed given his years of experience studying math, science and philosophy, where every minute detail is critical to understand.

He wrote about a “military plot” bubbling beneath the surface of day-to-day German society, reported on anti-Jewish violence, and noted the kind of widespread hunger that can fuel extreme ideologies.

While many officials still worried more about communism, Bell insisted there was another threat on the rise. He begged Allied leaders to lift the food blockade on Germany and consider a policy of economic support—all to head off the resentment he believed would someday explode.

Allied leaders read his reports, but they brushed them off as exaggerated. The idea of pumping money into a former enemy’s economy didn’t sit well with those who wanted harsh reparations. As a result, Bell's suggestion was dismissed—though it would later prove remarkably similar to the successful “Marshall Plan” of 1948, which invested $13.3 billion in rebuilding Western Europe.

This massive economic support program accomplished exactly what Bell had advocated for decades earlier: preventing extremism by addressing economic despair. By 1951, the recipient nations' economies had surpassed their prewar levels, achieving the stability that Bell had argued was crucial for lasting peace.

Bell returned home to Canada in late 1919, disappointed and dealing with health issues.

If Bell’s story had ended there, he might just have been another scholar with an extraordinary war story. But he never really let go of his obsession with Germany’s future. He taught philosophy for a while at Harvard and the University of Toronto, tried his hand at private business, and maintained quiet connections with his friends and contacts overseas that let him keep tabs on unfolding events in Europe.

In the 1930s, the seeds he had warned about in 1919 began to sprout.

Germany’s political chaos, hyperinflation, and national humiliation paved the way for Adolf Hitler’s rise. That’s when the intelligence community came knocking again. As a spy, Bell started travelling back to Germany in 1934, under the cover of a businessman. He was joined by his wife Hazel during these missions. Hazel deserves credit too for understanding her husband was an undercover operative and the risks that posed to both of them.

During these trips, Bell formed alliances with people like Wilhelm Runge, a radar researcher who helped sabotage Nazi technology from within. Between 1934 and 1943, Runge intentionally misled Hermann Göring about radar technology. In doing so, this meant Germany fell woefully behind in developing radar capabilities at a time when the Allies’ radar research and development advanced and a rapid rate.

Runge fed Bell intel about the state of Germany’s radar capabilities, which Bell made sure made it to the Allies. Runge’s deceit and collaboration with Bell gave the Allies the upper hand and was a huge reason the Allies gained naval superiority during WWII.

Bell routinely risked his life gathering and sending this information, as well as tidbits about Germany’s rearmament, internal politics, and looming dangers, to his Allied handlers.

Winthrop Bell’s network in Germany included academics, intellectuals, and covert allies who facilitated his espionage and provided critical insights. Bell’s former mentor Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology shaped Bell’s analytical approach to decoding Nazi ideology.

He befriended fellow philosopher and friend, Edith Stein, a Jewish convert to Catholicism, who later became a saint and was murdered at Auschwitz. Stein’s firsthand experience of Nazi antisemitism likely informed Bell’s warnings about Jewish persecution.

Bell also forged a professional relationship with the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, Niels Bohr, leveraging his intellectual reputation to gather intelligence without suspicion. Bohr’s connections provided Bell entry into high-society circles, aiding his espionage.

Then came 1939, and Bell’s reading of Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Using his academic background, philosophical training, and understanding of German society and culture, Bell quickly concluded that the Nazis had a plan for something far more sinister than just discrimination or forced emigration.

He believed they intended to wipe out entire groups of people. In articles he tried to publish in Canadian outlets, he used the phrase “racial extermination” at a time when almost nobody else imagined such a horror was possible.

It’s chilling that Canadian publishers dismissed his pieces as “alarmist” and refused to print them until after the war started. Even then, his warnings were overshadowed by the broader war news. It wasn’t until later that historians discovered how specific and early Bell’s predictions really were.

When World War II erupted, Bell was at his home in Canada and tried to get back into formal intelligence work with MI6. Unfortunately, his old contacts like Prime Minister Borden were gone, and the bureaucratic machine was no longer interested in an aging academic spy.

Officially sidelined, Bell still found a way to contribute. He ended up repairing Royal Canadian Air Force planes, drawing on his engineering background. This was likely the result of his brother Ralph Pickard Bell’s connections from his role as Director-General for Aircraft Production in Canada from 1940–1944. It wasn’t the cloak-and-dagger lifestyle he’d once had, but it showed how committed he was to Canada’s efforts.

After the war, Bell found himself returning to his first love: research and writing. He settled in Nova Scotia and began focusing on the story of the province’s 18th-century “Foreign Protestants,” a group of European settlers who shaped Nova Scotia’s cultural landscape.

He poured years of study into their background, travelling to archives and tracing genealogical records. The result was his scholarly book, The “Foreign Protestants” and the Settlement of Nova Scotia, published in 1961.

This book remains a landmark reference for anyone studying early immigration to Nova Scotia. It shows another side of Bell—the academic who loved piecing together historical puzzles. While it might seem like a big shift from espionage, it was just another way he used his careful mind and attention to detail.

During this time, Bell also became president of the Nova Scotia Historical Society (1951). He also donated a large part of his personal library to Mount Allison University—carrying on the tradition of helping future generations learn. That’s what he’d always done, whether he was sending intelligence dispatches from Berlin or writing footnotes about an old maritime graveyard, he always tried to make sure information passed to the people it mattered most to.

If you’re wondering why more Canadians don’t know Winthrop Pickard Bell’s name, the biggest reason might be that most of his espionage work was classified for decades. By the time those records were declassified, Bell had already passed away. He died on April 4, 1965, in Chester, Nova Scotia, without ever getting official recognition or medals, and he wasn’t celebrated like more famous spies.

Bell left behind two distinct legacies. First, there’s his undercover work, now revealed through documents and the efforts of researchers like Jason Bell (no relation), a University of New Brunswick scholar who spent years digging up old MI6 files. It shows a determined man who believed in Canada’s role on the world stage and tried to warn his country—and its allies—about threats no one else was taking seriously.

Second, there’s the historian. His careful research of Nova Scotia’s history preserved stories and genealogies that could have been forgotten. When you pick up his books or read about the “Foreign Protestants,” you might never guess they were written by someone who once dodged gunfire in Berlin while slipping telegrams to Allied leaders.

Why should we remember Winthrop Pickard Bell today?

Because his life shows what can happen when a person combines curiosity with determination. He moved from rural Nova Scotia to Harvard to German universities, refusing to let borders or wars stop him from seeking knowledge. When the world turned upside down, he found ways to fight back—first by spying, then by speaking out against Hitler’s plans, and finally by returning to scholarship.

To me, Bell’s story is a reminder that you never know how a single person’s efforts might ripple across history. His timely intelligence, if heeded, might have slowed the Nazi machine. His calls for economic aid might have eased the resentment that helped Hitler rise. And when official channels failed him, he still found ways to serve his country—like working on planes for the Royal Canadian Air Force during WWII.

Ultimately, Bell’s life asks us to think about all the uncelebrated Canadians who served in quiet ways. It also challenges us to wonder whether we’re ignoring any “unheeded warnings” today.

What Do You Think About Winthrop Bell’s Story?

Have you heard of Winthrope Pickard Bell’s story before?

Did you know that a Canadian predicted the rise of Naziism and the Holocaust? How frustrating is it to think that Bell was ignored? I can’t imagine what it must’ve felt like to have seen the signs and sounded the alarm, only to be dismissed and then have to witness WWII and all its atrocities play out. Do you think we still have spies operating in other countries that we’ll learn about decades from now?

Take a sec. to type a comment and share your thoughts and stories. As always, I look forward to reading them all!

Thanks a bunch for reading this story. It’s a pleasure to share Canadian stories like this with you.

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/winthrop-bell-great-war-hero-1.5161316

https://mta.ca/record/issues/2023-fall/unsung-hero

https://libraryguides.mta.ca/winthrop_pickard_bell/historical_organizations

https://mirror.csclub.uwaterloo.ca/gutenberg/1/0/1/1/10115/10115-h/10115-h.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Winthrop_Pickard_Bell

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02722011.2021.1945280

https://cchahistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Historical-Studies-vol-73-Final.pdf

Thank you, Craig, for your fascinating bios of all sorts of Canadians. These are people and achievements we ought to know about. I look forward to reading more.

Fascinating! What an interesting person. I’m glad Bell is getting some of the recognition he deserved. History is just full of lessons that we can take into the present. Bell’s story can teach us that warnings from those that have special insight could change the course of impending catastrophic events.

Also, I think it’s so cool that his studies began with philosophy which I think can be a powerful source of wisdom.