From First Round NHL Draft Pick to Alpine Mystery: The Duncan MacPherson Story

The disturbing questions behind a Canadian athlete's disappearance in the Austrian Alps

The red glove emerged from the ice like a signal flag, a forgotten hand reaching out from a frozen tomb. On July 18, 2003, as summer warmth softened the surface of Austria's Stubai Glacier, a resort employee stopped dead in his tracks. There, partially revealed by the melting snow, lay the answer to a question that had haunted two continents for fourteen years: What happened to Duncan MacPherson?

The discovery would shatter the official narrative that had been maintained for over a decade. It would confirm what Bob and Lynda MacPherson had refused to stop believing through eleven desperate trips to these mountains—their son never left this place. The broken snowboard still strapped to his feet told a story vastly different from the one they'd been fed by authorities who suggested Duncan had simply wandered off or abandoned his previous life.

But to understand what brought this promising young hockey player from the flat prairie landscape of Saskatoon to his final moments on an Austrian mountainside requires more than just the cold facts of his disappearance. It requires knowing the man himself—a physical defenseman with bone-rattling checks on the ice and a conversationalist's gentle nature off it.

Duncan MacPherson's story is one of dreams deferred and justice denied. It begins not with his death, but with his life—and the relentless love of parents who refused to let his memory disappear into the fog that shrouded the mountain on that fateful August day in 1989.

Duncan MacPherson was born on February 3, 1966, in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. He had a spark of independence from a very young age. His mother, Lynda, liked to tell the story of Duncan as a three-year-old who took the bus alone for a doctor’s appointment—no fuss, no worries. He just hopped on and off like it was the most natural thing in the world. As he grew, he poured that same fearless energy into everything he did, especially hockey.

If you were around Saskatoon in the early 1980s, you might remember him as a physical defenseman who played junior hockey for the Saskatoon Blades. He may not have been the most graceful skater, but you wouldn’t doubt his willingness to put his body on the line to throw a body check to prevent opponents from getting by him.

Teammates from that era still talk about him tossing open-ice hits that made crowds gasp and opposing forwards learn to keep their heads up. There’s an old adage in team sports like hockey that “defence wins championships” so players like MacPherson were highly sought after.

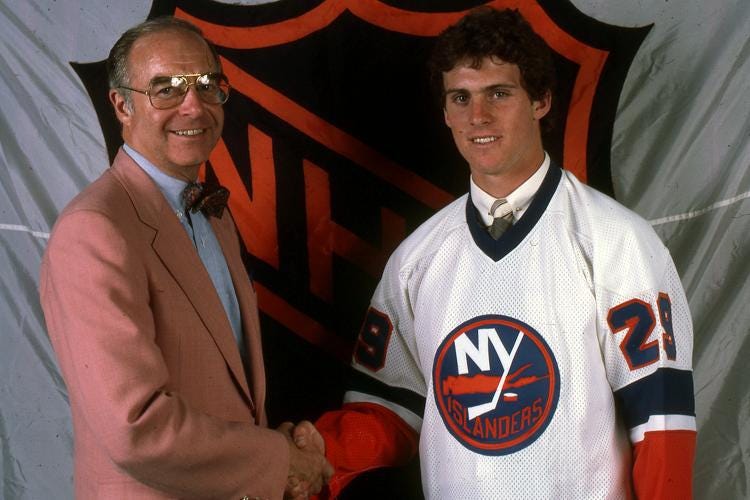

Talent scouts took notice of the teenage defender and as the 1984 NHL entry draft approached, MacPherson was expected to be picked. The New York Islanders were particularly impressed with the Saskatoon teen’s solid defence and drafted him 20th overall in 1984. For a kid from the Canadian prairies, getting picked in the first round was a dream come true.

MacPherson, his family, friends, and the community celebrated for weeks afterward. It seemed like the sky was the limit.

However, MacPherson’s physical play didn’t just punish his opponents, it also took a toll on his own body. Over the next four years, he battled to try to crack the Islanders’ lineup while continuing to improve his play during stints with New York’s farm teams in Springfield (AHL) and Indianapolis (IHL).

He won over fans in each of those cities, who appreciated Macpherson’s grit and determination. But injuries to both of his knees, a torn rotator cuff, and a major leg injury prevented MacPherson from making the leap to the NHL.

The Islanders made the devastating decision to release him in 1988. The high of being a first-round draft pick came crashing down around MacPherson who now found himself among the 99.975% of Canadian minor hockey players who never make it to the NHL.

By 1989, he was 23 and decided it might be time for a new path. Around this time, Ron Dixon, a Canadian millionaire with a controversial history in sports ownership offered MacPherson a job as a player-coach with the Dundee Tigers in Scotland. Resolved never to let injuries dictate his future, this sounded like the perfect next step to MacPherson. He saw it as a chance to see Europe, coach hockey, and keep pushing himself in something he loved.

It’s worth mentioning here, that while most of what is known publically about Duncan MacPherson revolves around his on-ice physicality and toughness. But off the ice, people who knew him best often called him a “gentle giant” with a conversationalist nature. Someone who could make anyone feel at ease. Confident but not cocky, independent but a team player and someone you could always count on when you needed a friend. Someone who understood that there’s much more to life than just hockey.

Before he was due in Scotland on August 12, 1989, Duncan took the opportunity to do a little travelling; a bit of a respite before throwing himself back into the hockey world. It was a small window of time that MacPherson saw as an excellent opportunity to reconnect with some of the many friends he’d made throughout his time in Saskatoon and playing hockey in the U.S.

On August 2, 1989, MacPherson took the train from Saskatoon to Edmonton, where he boarded a plane and flew to London. After arriving in Europe, he travelled to Frankfurt and then on to Nuremberg, in West Germany, where he stayed with a friend named George Pesut, who was also from Saskatoon. He then borrowed Pesut’s car and drove to visit another friend named Roger Kortko in Füssen before driving to Austria’s Stubai Alps.

MacPherson’s desire for a little mini-exploration of Europe wasn’t a surprise to anyone who knew him. Friends and family who knew MacPherson best describe him as having a wanderlust spirit. As he crossed Europe in the summer of 1989, he was able to scratch that itch. And while hockey was a big part of his life, it was far from his only interest.

Before the next chapter in his hockey career took place, he wanted to try snowboarding in the Alps. The Stubai Glaciers—a beautiful place with year-round snow and famed ski slopes—seemed to be the perfect place to do so.

On August 9, he rented a snowboard at the Stubai Glacier Resort, even though he had barely tried the sport before. The instructor who gave him a lesson that morning later recalled that Duncan was in top shape. He handled the basics quickly, then headed out alone to practice.

That day was unusually foggy though. By afternoon, only a few skiers were left on the hill. Some employees remembered seeing him head off on his own and disappearing into the fog that afternoon. That was the last time anyone would see Duncan MacPherson for the next 14 years.

When MacPherson’s family were contacted by Ron Dixon on August 16, and told that Duncan had failed to report for work in Dundee by August 12, they immediately grew worried. They contacted authorities in Canada, Germany, and Austria to ask for help. Some officials brushed them off, suggesting that a young man might have simply met someone, gone on a romantic detour, or changed his mind.

Duncan’s parents, Bob and Lynda, knew that wasn’t like him at all. So they hopped on a plane, determined to do their own investigating.

On September 22, a big break surfaced when a parking attendant responded to seeing a plea from the MacPhersons on a local television station and called in a tip that a red Opel matching the description of the car Duncan borrowed from his friend, had been sitting in the resort parking lot for six weeks.

Inside the car, police found some of Duncan’s belongings, including his passport, a bag of rotten fruit, and a cassette from a local music store. At first, the authorities did little to preserve evidence—an unfortunate pattern that would echo in the years to come.

A big clue about Duncan’s last known location was a receipt from his snowboard rental from August 9. According to the resort’s records, though, that same snowboard was supposedly returned later that same day. The question became: If he returned the gear, where had he gone after that? And why leave his friend’s car behind? Things weren’t adding up.

The MacPhersons kept coming back to the Stubai Glacier region over the next months and years. Travelling to the region a total of 11 times over the next 14 years. At every step, something felt off. Local officials insisted Duncan must have wandered off-trail, maybe falling into a crevice. The resort staff maintained that Duncan wasn’t their problem—if he ventured beyond marked slopes, he alone was responsible.

A year before Duncan’s disappearance a skier at the resort had fallen into a crevice and was later rescued. So there was a precedence for that sort of thing happening. However, over the years, the MacPherson’s and their private investigators felt like the stories from resort staff didn’t quite add up. But without Duncan’s body, there was no proof of anything.

The more the case was discussed, the more conspiracy theories started swirling around. Some folks suggested more bizarre theories—like the rumour he might have been recruited by the CIA and disappeared by them with Duncan’s consent, or that he chose to vanish and start a new life with a woman he might have met and wanted to leave hockey and everything in his previous life behind him.

None of that fit the Duncan his family and friends knew: a family-oriented guy who was planning a fresh start in Scotland. Bob and Lynda refused to quit. They dipped into their savings for their repeated trips to Austria, chasing leads that mostly went nowhere and paying for private investigators and funding their own missing person ads and campaigns.

The Austrian police sometimes seemed indifferent. The Canadian officials often brushed the MacPhersons aside. The family scoured local hostels, talked to shopkeepers, and cajoled the media for help—anything to pry out new information.

Then, on July 18, 2003, the Stubai Glacier was in the midst of a warm summer melt when an employee on routine patrol spotted a red ski glove emerging from the ice in the middle of a well-used slope. A partial figure was also visible beneath.

The authorities were called, and an ID card, along with other items on the frozen body, proved it was Duncan MacPherson. The red Opel, the lack of concern from authorities, the swirling rumours, the conspiracy theories—everything had finally led to a grim conclusion: Duncan never left that mountain back in 1989.

When the Austrian authorities recovered Duncan’s body, they placed it in a local funeral chapel, with no official autopsy and no one properly documenting the condition of his remains. That seemed suspicious to the MacPhersons. Once they arrived, they discovered that Duncan had been found not off in some remote ravine, but right near a well-used ski slope—contrary to all the statements they’d heard for years.

Then came the biggest shock: the rented snowboard that Duncan supposedly returned was still strapped to him, broken in two, although the resort always maintained it had been returned safely.

The MacPhersons sensed that people on the mountain must have known more than they were saying. A proper forensic examination might have revealed exactly how Duncan died, but Austrian officials moved quickly to close the file, effectively labelling his death an unfortunate crevasse accident.

Meanwhile, Bob Lynda and their investigators could easily identify evidence of major injuries. When Duncan was found, he had severed limbs, sharp fractures along bone shafts, extensive avulsion of muscle, tendon, and skin, and damage to the board that looked like mechanical cutting, not the random grind of ice. The MacPhersons asked for more tests and an autopsy to be completed, but those requests went nowhere.

Back home in Saskatoon, the family reached out to forensic pathologists and journalists who shared their suspicions. One theory emerged: Duncan may have suffered a snowboarding mishap, possibly injuring his leg so he couldn’t move. A snowcat, grooming the slope in poor visibility, might have run over him by mistake.

If that happened, the driver could have panicked, seeing the Canadian tourist horribly injured—maybe dead—and decided to hide the truth rather than face legal trouble or put the resort’s reputation at risk.

John Leake, who wrote a book called Cold a Long Time: An Alpine Mystery, dug deep into the details of MacPherson’s case. He pointed out tool-like gouges on Duncan’s body and the broken snowboard. A few pathologists agreed that natural glacial movement alone wouldn’t explain such cuts. The shape of the fractures on his limbs suggested machinery.

Resort staff had been defensive from the start when questioned about Duncan’s dissapearance. The local police had shown little initiative in investigating staff or conducting thorough interviews. There always seemed to have been a culture of silence revolving around the case.

Even so, there was no “smoking gun.” No groomer operator ever came forward to confess. Records were missing or contradictory. Reports changed about exactly where and how Duncan’s body was retrieved from the glacier. And since his remains were cremated before a real forensic exam, a huge piece of potential evidence was lost forever.

The MacPhersons kept pushing for accountability, turning to the Canadian government, the courts, and anyone who would listen. They uncovered redacted diplomatic files and contradictory Austrian statements. Austrian officials stuck to their story: Duncan had simply fallen into a crevasse or out-of-bounds area. By the time the glacier melted enough to reveal his body, they argued, natural forces had caused the trauma.

But if you look at the actual place where he was found, it was 25 or 30 metres from a tow lift—within normal boundaries. His parents argued that if he had been lying injured on the slope, someone should have seen him or at least been compelled to search when he failed to return his snowboard gear that evening.

To this day, there has been no formal apology or compensation offered to the MacPherson family. They applied to the European Court of Human Rights, claiming that Austrian authorities botched or covered up the investigation. As of the last update I can find, that case remains in limbo. Meanwhile, the family spent much of their life savings travelling to Austria in search of answers.

The question of what really happened on the Stubai Glacier remains unsolved. Some believe the original version of events: a plain accident in a crevasse, with the glacier’s ice warping his remains over time. Others agree with the snowcat theory, pointing out that the injuries seemed too clean and the official statements too inconsistent. Sadly, the MacPherson’s may never know the truth.

Duncan’s story now stands as a reminder that winter sports, even for skilled athletes, carry real risks. It also highlights the difficulties families face when a loved one goes missing or dies abroad. Different policing standards, language barriers, and the desire of resorts to protect their business can complicate any search for the truth.

For Canadians, Duncan’s story resonates in many ways. We grow up hearing about how hockey unites us, and how young players dream of the NHL. Duncan had that dream, and when injuries got in the way, he looked outward—coaching in Scotland, taking up snowboarding on the side, and finding new adventures. His final trip, however, ended in a heartbreak that stretched across borders and decades of unanswered questions.

Tragically he went from being on top of the world, en route to living the dream of playing in the big leagues to dying alone on a mountain halfway across the world under suspicious circumstances that have devasted his family, friends, and community. All the supporters he’d earned over the years both through his on-ice gritty play and his off-ice warm and engaging personality, still mourn the loss of their hero, and friend.

Today, the MacPherson family still presses on. They want a real admission of what took place. They believe their son died because someone acted irresponsibly—then tried to hide it. They also hope that by telling Duncan’s story, they might prevent another tragedy on a foggy slope, somewhere far from home.

If you ever find yourself in Saskatoon and chat with folks who followed the case, you might hear them mention how kind, brave, and open-hearted Duncan was before everything changed. In local hockey circles, the memory of his no-nonsense style on the ice still lives. Across the country, Canadians continue to learn about his disappearance and the mysteries left behind.

Perhaps that’s the final message from his story is that if you set out on a bold path, you deserve the chance to finish it safely. When that chance is taken away, families, communities, and sometimes entire nations, are left to seek justice and understanding—even if it takes years or decades to uncover.

What Do You Think About Duncan MacPherson’s Story?

Have you heard of the disappearnace and death of Dincan MacPherson before?

For me, this story is right up there with the Bill Barilko disappearance that Gord Downie of the Tragically Hip once sang about. Can you imagine the rollercoaster the MacPherson family has gone through as they watched Duncan grow and develop into a top-tier hockey prospect to being plagued by injuries, to disappearing for 14 years and then being found dead and never finding any closure as to how and why he died?

Take a sec. to type a comment and share your thoughts and stories. As always, I look forward to reading them all!

Thanks a bunch for reading this story. It’s a pleasure to share Canadian stories like this with you.

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story

https://www.metafilter.com/137516/The-disappearance-and-reappearance-of-Duncan-MacPherson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duncan_MacPherson

https://www.esquire.com/sports/a1835/esq0104-jan-game/

https://vocal.media/chapters/a-mystery-in-the-alps

https://www.reddit.com/r/hockey/comments/40sr84/wayback_wednesday_the_death_and_disappearance_of/

https://www.coldalongtime.com/pages/discovery-location-fundstelle

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/22/sports/hockey-the-body-of-ex-isles-draft-pick-is-found.html

https://www.hockeydb.com/ihdb/stats/pdisplay.php?pid=3634

https://www.coldalongtime.com/pages/disappearance-and-discovery

https://www.hockey-reference.com/draft/NHL_1984_entry.html

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/hockey-player-s-body-found-after-14-years-1.394735

http://www.espn.com/nhl/news/2003/0721/1583771.html

https://www.coldalongtime.com/

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/new-book-uncovers-details-of-cold-case-1.1196325

https://gdrinnan.blogspot.com/2012/05/whatever-happened-to-duncan-macpherson.html

https://www.hockeydraftcentral.com/1984/84020.html

https://pucktavie.blogspot.com/2017/01/le-mystere-duncan-macpherson.html

Duncan’s mother here: thanks for telling Duncan’s story. You have done a good job of telling what is a long and complex story.

Hi Craig - Duncan is my brother, we appreciate your time and energy you put into telling his story, you've obviously done some good research. Thank you.