The Formula of Defiance: Maud Menten's Scientific Odyssey

From Port Lambton to Berlin: A Canadian woman's quest to solve medicine's molecular mysteries

As dawn broke through the frost-covered windows of a Berlin laboratory on a winter morning in 1913, the pungent smell of chemicals lingered in the air. Dr. Maud Menten squinted at her notebook, her eyes burning from eighteen straight hours hunched over glass beakers and microscopes. Her fingers, stained with reagents, trembled slightly as she recorded the final measurements.

"It works," she whispered, her breath visible in the chilly morning air.

The thirty-four-year-old Canadian woman had just validated an equation that would eventually transform medicine forever. Beside her, Dr. Leonor Michaelis nodded in quiet acknowledgment, both scientists knowing they'd uncovered something profound in the behaviour of enzymes—the invisible molecular workers inside every living cell.

Maud straightened her aching back and gazed out at Berlin awakening below. How far she had come from the riverside hamlet of Port Lambton, Ontario, where girls weren't supposed to dream of laboratories and making medical breakthroughs. How many oceans and mountains and prejudices she had crossed to reach this moment.

She couldn't possibly know then that nearly one-third of all future medications would trace their development to this equation scratched in her notebook. She couldn't know that children with scarlet fever, patients undergoing surgery, and millions suffering from chronic conditions would someday benefit from her persistence.

All she knew, in that cold German laboratory, was that neither distance, nor difficulty, nor the dismissive attitudes of men would stop her from uncovering nature's secrets.

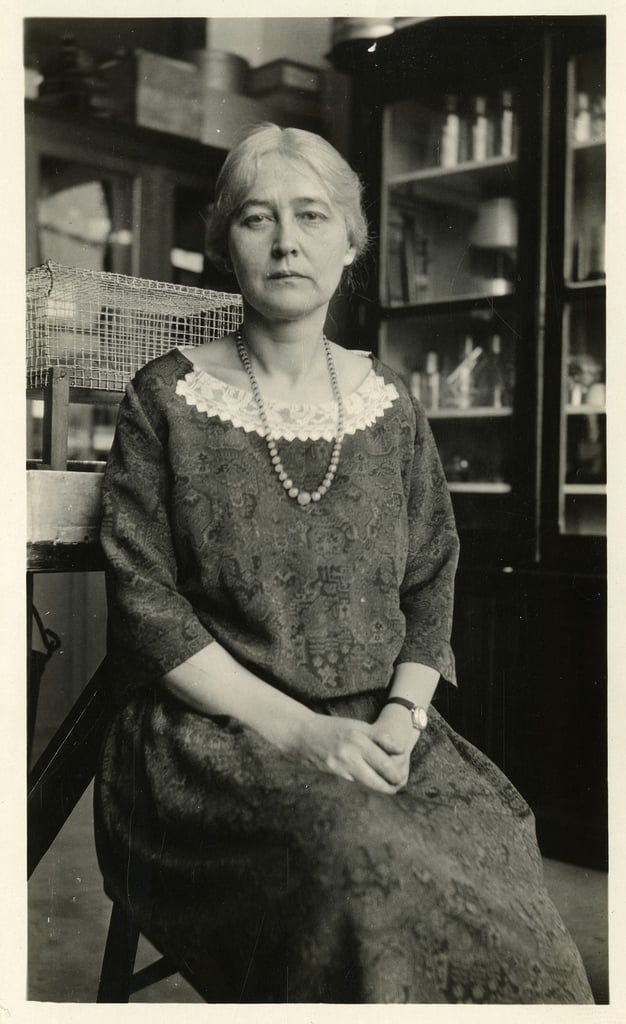

This is the story of Maud Leonora Menten—biochemist, physician, mountaineer, and arguably one of Canada's most consequential scientists that history nearly forgot.

Maud Menten was born on March 20, 1879, in a small riverside community called Port Lambton, Ontario. Her family later moved to Harrison Mills, British Columbia, when she was ten years old. If you try to imagine the late 1800s in that remote region, you can picture the thick forests, dirt roads, and limited educational opportunities for young girls. Yet Maud’s mother homeschooled her, and Maud quickly showed a knack for learning.

By the time she was 13, a one-room school opened in Chilliwack, about two-and-a-half miles away from her home.

Most girls in her position might have stayed back to help with chores or family duties. Instead, Maud travelled by ferry and pony every day to attend classes. This is one of the earliest glimpses we have of her determination: distance, difficulty, and social expectations didn’t stop her. It’s likely this can-do spirit laid the groundwork for everything she accomplished later on.

Around 1900, Maud left Harrison Mills and enrolled at the University of Toronto.

At that time, women in higher education were a rarity. Many people believed that serious scientific research wasn’t a “woman’s realm.” Maud didn’t let that attitude stop her. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1904, then went on to earn a Bachelor of Medicine (M.B.) in 1907.

Maud had developed a voracious appetite for research and wanted to continue learning everything she could about medicine and in particular biochemistry.

But, even though she had spent years proving her academic worth, Canadian labs had policies and cultural biases that prevented women from doing research. So she had to seek opportunities outside her home country. It’s worth pausing here to imagine how big a step that was. Today, travelling to another country for a job is fairly routine, but in the early 1900s, women travelled alone far less often, and professional positions for them were scarce.

Maud was among the few women who dared refuse to be limited by what society thought she should and shouldn’t do.

So, still in her twenties, Maud moved to New York to work at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. Unable to set up her own lab in Canada, she jumped into experimental cancer work under top scientists in the United States. In 1910, she published the institute’s first monograph on using radium bromide for treating cancer in rats—a pioneering effort at a time when X-rays and radioactive elements were still new in cancer therapy.

While at Rockefeller, she also completed an internship at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children.

Eventually, in 1911, she returned briefly to Canada to complete her Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) from the University of Toronto. In doing so, she was one of the first Canadian women to receive a medical doctorate. Yet, although she held advanced degrees, she still struggled to find full backing for her research in Canada.

That frustration drove her to consider travelling to Europe, a bold move for anyone, let alone a single woman facing professional skepticism at every turn.

In 1912, Maud decided to journey to Berlin to study under biochemist Leonor Michaelis. She funded this trip herself, which was no small undertaking. In 1913, the two of them published what came to be known as the “Michaelis-Menten equation,” a crucial tool in understanding how enzymes function.

If you’ve ever used medication for high blood pressure or taken a pill to manage a chronic condition, you’ve benefited from that equation’s principles without even knowing it.

At its simplest, the Michaelis-Menten equation describes the rate at which enzymes—tiny protein catalysts in our bodies—convert substances (called substrates) into different chemicals. By clarifying how fast enzymes work, scientists could then figure out how to design drugs to either speed up or block these processes in the body. This discovery mattered hugely for pharmacology, and it remains a building block of biochemistry courses around the world.

Not bad for a Canadian medical graduate who’d been barred from doing research in her own country!

It’s worth pointing out, that the paper that originally introduced the Michaelis-Menten equation listed her as “Miss Maud L. Menten,” and not “Dr. Maud Menten,” even though she possessed her medical doctorate. Some even suggest that she might have been the primary driving force behind that equation, but standard practice at the time tended to give more credit to men.

Still, she forged ahead, focusing on the next research question and the next patient who could benefit from her work.

After Berlin, Maud continued expanding her studies. By 1916, she had earned a Ph.D. in biochemistry from the University of Chicago—another notable feat for a woman at the time. She then held positions at various institutions in the United States, including Western Reserve University in Cleveland and Barnard Free Skin and Cancer Hospital in St. Louis.

Some of her efforts during those years included:

Cancer Research: Building on her earlier work with radium treatments.

Histochemistry: Investigating chemical markers in tissues (this would lead her to later develop a dye-based technique to spot certain enzymes).

Immunology: Exploring how to prevent diseases such as scarlet fever, a serious childhood illness then.

At every turn, Maud encountered labs that might hire her as a research fellow or demonstrator, but not necessarily promote her to the top levels of faculty. Gender bias often meant she did work beneath her qualifications. Even so, she continued to publish paper after paper.

By 1923, Maud joined the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine faculty as an assistant professor.

While working in Pittsburgh, Maud Menten tackled more than just enzymes and children’s illnesses. She looked at how the human body responds to anesthesia and how surgical shock could be prevented. At one point, she teamed up with surgeon George Crile in Cleveland to study acid-base balance in the blood during operations.

They discovered that when blood grows too acidic, patients face a higher risk of complications or even death. Their findings helped drive safer anesthesia methods—an important leap forward in an era when surgery was still a major gamble for many patients.

Menten also did extensive research on bacterial toxins.

She wanted to understand how microbes cause disease, especially in children. Her focus on scarlet fever proved crucial. Alongside colleagues, she purified a toxin produced by streptococci bacteria. This work contributed to strategies that later reduced scarlet fever mortality rates and improved public health measures. Menten’s research was part of the progress that made effective treatment of scarlet fever possible.

Over time, she advanced to associate professor and, eventually, full professor. Sadly, her promotion to full professor came in 1948, when she was 69—just two years before she retired. It’s a telling fact about the academic climate: decades of groundbreaking research, yet official recognition arrived only when she was near the end of her career.

Alongside her university role, Maud served as the pathologist at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh from 1926 to 1950.

There, she studied a range of childhood diseases, from pneumonia to meningitis. She worked day and night, often logging 18-hour days. Colleagues saw her as fearless, brilliant, and always ready to pursue new leads. Imagine the dedication it takes to hold a demanding hospital role while researching new techniques in enzyme detection. It tells you a lot about Maud’s character: she never seemed to let obstacles or exhaustion slow her down.

This chapter in her life also included major contributions to histochemistry.

In 1944, she co-developed the azo-dye coupling reaction. That’s a fancy way of saying she found a chemical method to identify alkaline phosphatase (an important enzyme) in tissues. This technique helped pathologists pinpoint liver and kidney problems, and it’s still a staple in many labs today.

While Maud threw herself into scientific work, she also maintained a rich personal life.

She somehow made time for painting, clarinet playing, and even mountain climbing—an unusual hobby for a woman of her era. She was also multilingual, picking up French, German, Italian, Russian, and at least one Indigenous language: Halkomelem.

If you ever saw Maud around campus in those days, you would have spotted her wearing one of her signature eye-catching outfits, including what one colleague recalled as “Paris hats” and “Buster Brown shoes.”

People described her as a “petite dynamo.” She balanced a love for the outdoors with her passion for lab research, and she never seemed to care if others found her lifestyle unusual. One reason she likely felt so at ease in her own skin was her unwavering confidence in her research pursuits. When you spend years tackling major questions like cancer treatment and the basics of enzyme chemistry, day-to-day concerns often pale in comparison.

Despite her many accomplishments and widespread travel, Maud Menten never married.

While we can’t know every personal reason behind that choice, it’s clear she devoted much of her life to scientific pursuits. In early 20th-century Canada, many women faced pressure to step back from professional work once they married. That social climate might have prompted Maud to guard her independence. She seemed drawn more to the idea of pushing scientific boundaries than settling into expected domestic roles.

Over and over, she proved that her dedication to research was unwavering—perhaps because she believed, and rightly so, that her work had the power to improve medical science for everyone.

For all her focus on the lab, Maud was not a distant figure. Colleagues spoke of her warmth, wit, and courtesy. She was known for her dignity but also for her sense of humour. Friends in Pittsburgh described her as “unobtrusively modest,” always crediting those who worked alongside her. Yet they never failed to mention her unstoppable enthusiasm for research.

One can imagine her stopping in the hallway, brimming with excitement about a new enzyme experiment or a histochemistry finding. By all accounts, she made those around her feel curious and bold enough to explore what science could uncover next.

In 1950, at age 71, Maud formally retired from the University of Pittsburgh. She had spent decades there juggling teaching, lab work, and her role as pathologist at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh. Yet her retirement didn’t mean she left research altogether. Almost immediately, she moved back across the continent to British Columbia, where she joined the British Columbia Medical Research Institute to continue her cancer studies.

This decision seems perfectly in line with her character: even in her seventies, she was still excited and driven to investigate new methods for fighting cancer.

Sadly, Maud’s health began to decline in 1954. Severe arthritis forced her to end her active lab work, which must have been a heavy blow for someone who had devoted her entire life to science. She then returned to Ontario, settling in Leamington so she could be closer to her remaining relatives.

It was there that she spent her last years, reflecting, perhaps, on the long journey that started back in Port Lambton and led her through medical schools, labs, and research institutes in multiple countries.

On July 17, 1960, Maud Menten passed away in Leamington, Ontario, at age 81. Although her name wasn’t widely recognized at that time—certainly not to the degree of some of her male colleagues—she left behind a remarkable legacy of scientific discoveries and a collection of research papers that would influence biochemistry for generations to come.

It would take several decades before Maud Menten received the national praise she deserved.

But, in 1998, 38 years after her death, she was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame. At last, she was acknowledged as one of Canada’s medical pioneers—a woman whose work helped shape our modern understanding of enzyme kinetics and disease treatment.

Today, if you travel through Port Lambton, Ontario, you can find a commemorative bronze plaque celebrating her life.

The University of Toronto, where she earned her earliest degrees, has also installed an Ontario Heritage Trust plaque in her honour. In classrooms around the world, her name now appears in biochemistry textbooks whenever the Michaelis-Menten equation is introduced. Students often learn the phrase “Michaelis-Menten kinetics” without immediately realizing that one half of that duo was a Canadian woman who fought tooth and nail just to do research.

Maud Menten’s story speaks strongly to anyone interested in science, but especially to young women in STEM fields.

Her willingness to leave Canada in pursuit of lab opportunities, her all-night stints examining enzyme reactions, and her refusal to accept the limits society placed on her, are all parts of a bigger message: breakthroughs happen when determined people are free to follow their curiosity.

More than a century after she first published her work, the Michaelis-Menten equation still underpins much of what we know about how medicines function in the body. Meanwhile, the dye methods she helped develop remain essential in pathology labs worldwide.

Maud Menten’s life reminds us that history isn’t always fair in how it praises its heroes.

Even though her name might not yet appear in every Canadian history textbook, her resilience and intellect left a legacy that ripples through modern medicine. She grew up in modest circumstances, yet she travelled internationally to pursue research. She faced institutional sexism that slowed her career advancement, yet she persevered and published dozens of influential papers.

At a time when few women held advanced scientific degrees, Maud pushed boundaries in cancer research, infectious disease, enzyme kinetics, and more.

I hope you’ll remember her story the next time you see Canadian accomplishments in science celebrated. Much of our country’s heritage is shaped by individuals like Maud Menten who broke new ground, often without a spotlight. Her example encourages us to recognize and champion other unsung heroes in our midst.

Let her journey inspire you to look for opportunities in your own life where dedication can overcome obstacles.

What Do You Think About Maud Menten’s Incredible Story?

Have you heard of Maud Menten before?

Or have you studied biochemistry and heard of the Michaelis–Menten equation? Did you realize that many of the advancements in modern medicine are largely attributable to one Canadian woman who society tried to tell not to pursue a career in medicine?

Can you imagine what a culture shock it must have been to go from being homeschooled in rural Ontario to a one-room rural schoolhouse in BC to living and working in 1912 Berlin with a stop in New York City’s Rockefeller Institute along the way?

Take a sec. to type a comment and share your thoughts and stories. As always, I look forward to reading them all!

Thanks a bunch for reading this story. It’s a pleasure to share Canadian stories like this with you.

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maud_Menten

https://www.bcmag.ca/the-incredible-life-of-maud-menten/

https://www.thewhig.com/2013/03/04/ive-stirred-them-up-so-now-i-can-go

https://awis.org/historical-women/dr-maud-menten/

https://www.heritagetrust.on.ca/plaques/maud-leonora-menten-1879-1960

https://www.theobserver.ca/2014/04/27/maude-menten-overcame-societys-attitudes-about-women

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11436281/

https://www.lambtonmuseums.ca/en/lambton-heritage-museum/maud-menten-and-mary-jane-hutton.aspx

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Maud-Leonora-Menten

https://www.cdnmedhall.ca/laureates/maudmenten

https://definingmomentscanada.ca/insulin100/stem-women/maud-menten/