Stalactites & Spotlights: The Rise and Fall of The Cave Supper Club

How a Vancouver nightclub once brought the world's biggest stars to Canada

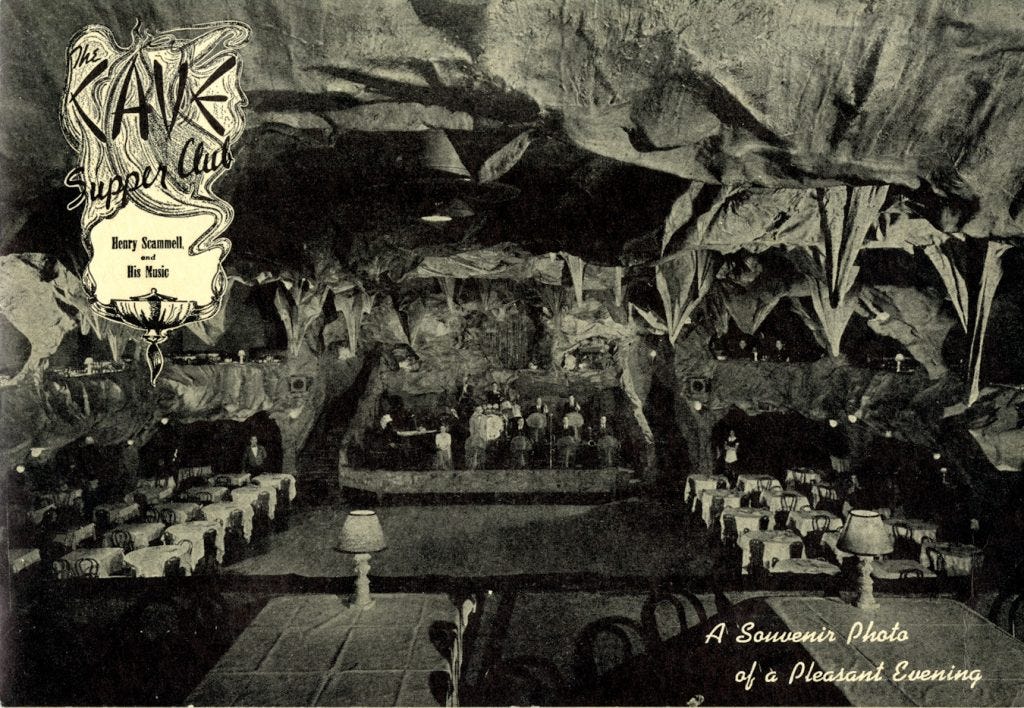

The year is 1963. You step through the doors at 626 Hornby Street and suddenly you're underground—or at least that's the illusion. Stalactites hang from the ceiling, glittering under soft lights. The air smells faintly of cigarette smoke, perfume, and whiskey. Around you, Vancouver's elite mingle in evening gowns and suits, their excited whispers rising above the clinking of glasses.

The house band strikes up its first notes as the lights dim further. A hush falls over the crowd. Tonight, Louis Armstrong will take the stage, his trumpet about to fill this artificial cavern with sound.

Welcome to The Cave Supper Club: Vancouver’s northern answer to Las Vegas. For over four decades, this was where the impossible happened nightly. In the heart of a Canadian city, an underground wonderland came to life, hosting the world’s greatest entertainers as they dazzled audiences.

You might not expect to find a secret grotto in the center of Vancouver. Yet for more than four decades, that’s exactly what The Cave Supper Club offered.

Anyone stepping inside the main doors on 626 Hornby Street was transported into a quirky underworld, complete with papier-mâché stalactites hanging from the ceiling, stone-like walls, and dim lights that gave the club an otherworldly glow.

It soon became famous not just for its fake cavern décor but also for its lineup of legendary performers who saw The Cave as a prime Canadian stop. For a long time, folks in Vancouver felt a certain pride in knowing that their city could welcome acts on par with Las Vegas and New York.

The Cave’s story starts in the mid-1930s. Back then, a man named Gordon King and his family were running the original Cave in Winnipeg, which had opened in 1935. Encouraged by that club’s success, they decided to expand into Vancouver.

So in 1937, the Vancouver Cave Supper Club opened its doors. Locals had seen nightclubs before, but nothing quite like this. Its whimsical interior, draped in faux rock formations, drew crowds who were just as fascinated by the décor as by the entertainers on stage.

People waited in long lines and came dressed in their best. One musician, Oliver Gannon, remembered it simply as “the gig in the city.” Vancouver had lots of interesting venues but, the Cave was the place to be.

In the early days, Gordon King and his family passed the ownership baton around a few times. George Amato briefly held the club before sold it to Isy Walters around 1950. That was when things really started to pick up.

Isy Walters had been busy in show business long before he arrived at The Cave. He’d owned the State Theatre on Hastings Street, Vancouver and worked hard to bring big names to the city. At The Cave, he set about transforming it from a quirky theme club into a top-tier entertainment destination.

A defining moment in the venue’s history came in 1954 when Vancouver granted dining-lounge liquor licenses to select businesses, including this one. Today, it might seem unthinkable to attend a live music show without a drink in hand, but at the time, this was a groundbreaking and exciting change.

Vancouver’s older liquor laws had been pretty strict, and letting patrons have a cocktail with their supper while watching a show changed the city’s social life. Suddenly, clubs could now afford larger acts and fill seats more consistently because of the demand for, and sale of, alcohol.

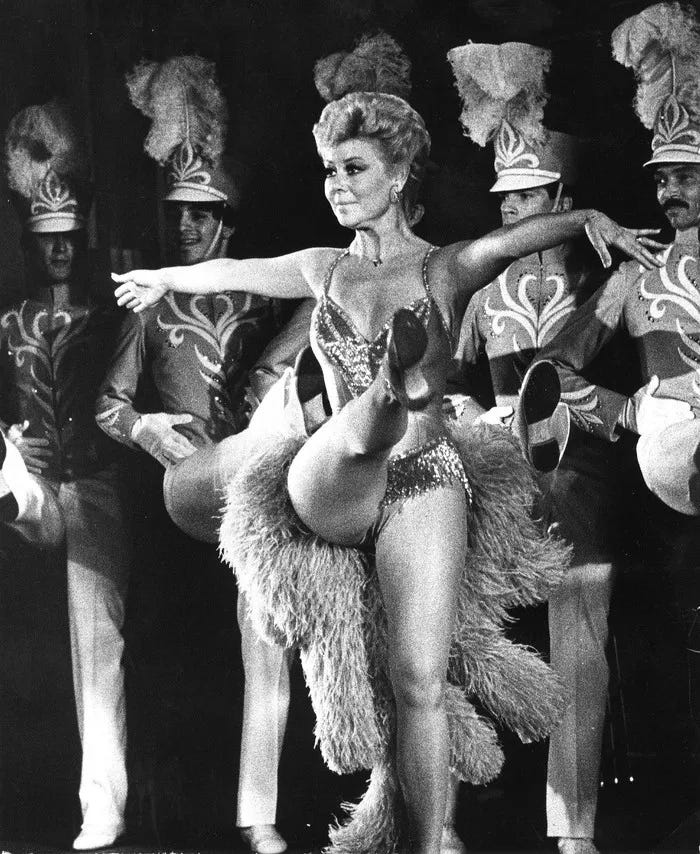

Walters ratcheted things up further by introducing showgirls, dancers, and bigger production values for shows at the Cave. He wanted to bring a taste of Las Vegas to Vancouver that included show-stopping music numbers, glamorous dancers, and an air of novelty that would dazzle audiences used to more modest nightlife.

It wasn’t long before The Cave became known for its “Ziegfeld-style” productions: lavish performances complete with intricate choreography, dramatic lighting, elaborate sets, and even collapsible staircases.

While striptease acts were drawing crowds elsewhere, The Cave’s “Van Vegas” vibe maintained an air of sophistication, making it a favourite among wealthy tourists and loyal local patrons alike. One local recollection put it this way: “Vancouver was booking acts that were now comparable with the stages of Las Vegas, and was pushing our city to a cultural hub.”

Audiences started including out-of-towners staying at the Hotel Vancouver or the Georgia Hotel as the venue helped bolster the local economy.

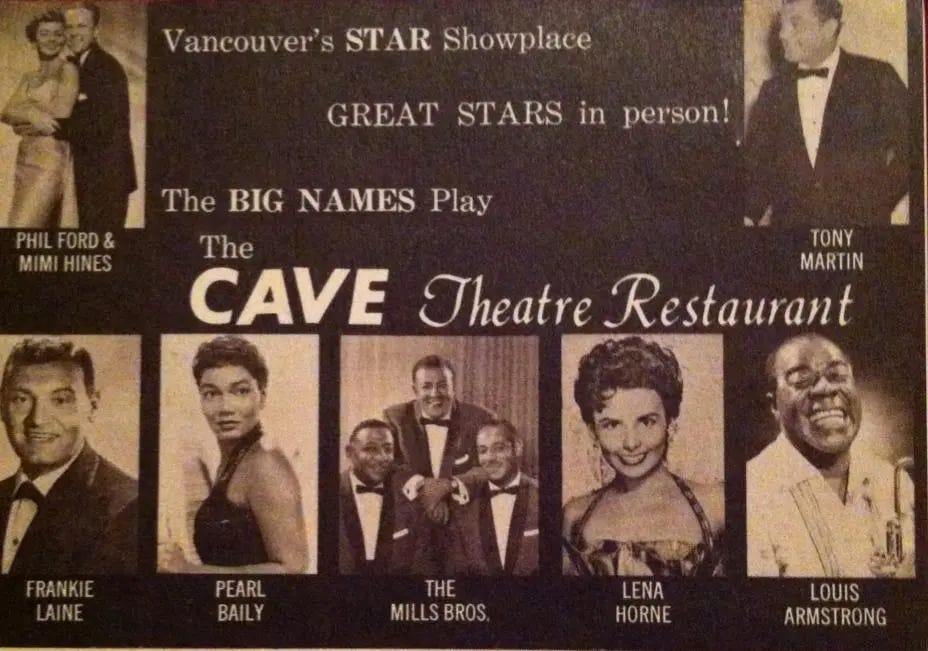

From the 1950s onward, The Cave’s lineup was about as star-studded as any place you can imagine from that era. Louis Armstrong performed there in the early ‘60s, Ella Fitzgerald took the stage, Tony Bennett sang, and Ray Charles wowed the crowds.

Johnny Cash, Fats Domino, Ike and Tina Turner, Duke Ellington, Gypsy Rose Lee, Bette Midler, Roy Orbison, and Liza Minnelli also graced its stage.

Oh, and don’t forget to add The Supremes, The Temptations, James Brown, Chuck Berry, and quite a few more to that list. You get the idea. It was an international who’s who of famous musicians and performers and it was all happening right here in Canada.

Many of these artists treated The Cave as a test run before heading to the Las Vegas strip. There’s a quote from John Hykawy, a longtime bellman at the Georgia Hotel: “The Las Vegas shows were always tested on the Canadian market at the Cave Supper Club, because the Canadian audiences in those days were very hard to arouse.”

In other words, if you could win over a reserved Vancouver crowd in a dimly lit cave, you’d have no trouble conquering Vegas. Mitzi Gaynor, a renowned American actress, singer, and dancer, had a significant connection with The Cave. She frequently used the venue as a testing ground for her stage acts before taking them to Las Vegas, a strategy that contributed to her success in the entertainment industry.

The Cave didn’t just bring in big global stars, though. It also provided opportunities for local musicians. The house band, led by saxophonist Fraser MacPherson for a time, backed many visiting stars.

It allowed homegrown talent to play with top names from the U.S. and beyond, which helped give a healthy boost to Vancouver’s music scene. Some local acts used the Cave as a place to network and make contacts that would open other doors in the music industry.

Isy Walters, often called “the true innovator” of The Cave, passed the ownership along in 1958, but didn’t abandon the nightlife world. He and his son Richard opened Isy’s Supper Club, another top spot in the city. Throughout the 1960s, The Cave and Isy’s were the two biggest forces in Vancouver’s nightclub scene.

As for the Walters family, it wasn’t just business. Their Edgemont Village home became an informal after-party zone for stars who wanted to mingle away from the spotlight.

Famous performers like Richard Pryor or The Everly Brothers would drop by the home while passing through town. Tamara Walters, Richard’s daughter, once recalled how Pryor even once took her and her sister to the zoo. Sammy Davis Jr. would come to Sunday meals. These gatherings were a little more interesting than your standard backyard barbecue.

By the 1960s, The Cave had a reputation for being top-tier. It was the first Vancouver club with a liquor license, and it had that magical set of ingredients: top bookings, flashy stage shows, and a space that felt special.

People used to say that they’d get dressed to the nines just to line up outside, whether or not a big headliner was scheduled. Some nights, you might see a burlesque act. On others, you might catch an elegant jazz singer. While the city was conservative in many ways, The Cave provided a glimpse of a larger nightlife that was typically associated with bigger cities.

But unfortunately, nothing lasts forever. As the 1970s rolled in, tastes began to shift. Younger audiences gravitated toward rock music, punk, or disco. Some of these styles found a place at The Cave for a while, but the club struggled with how to present them.

One week they might feature Bette Midler, who was playing her blend of bawdy jokes and jazz-inflected tunes. The next, they might host the local punk band Pointed Sticks, which probably confused the older regulars.

The Cave was trying to attract a wider range of audiences but ended up with inconsistent attendance. Some nights, they did very well; other nights were a bust. By trying to be a place for all tastes and genres, it lost its unique glitz and glamour.

At the same time, booking major acts was becoming trickier. The best acts no longer wanted to do long engagements in a supper club environment. They could sell more tickets in arenas or large concert halls.

A big star who used to do a two-week run at The Cave might now come to town to perform for only a single night at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre.

Local dancers and entertainers also found gigs in other places, making it harder to put together big production numbers. And as disco clubs popped up elsewhere in the city, The Cave’s cave-like setting started to feel outdated.

There were ownership changes during this phase of the Cave’s journey as well. Danny Baceda, who had opened Vancouver’s Oil Can Harry's in 1966—a popular venue for jazz, R&B, psychedelic soul, and garage music bought The Cave in 1971, along with Isy’s Supper Club. But Bazeda went into receivership within a year.

Stan Grozina bought The Cave Supper Club in 1973 and invested $75,000 in renovations. Grozina was originally from Slovenia. During World War II, he spent time in German labour camps before immigrating to Canada with minimal resources.

He initially settled in Winnipeg, where he became involved in the construction industry. Eventually, he retired to Vancouver and decided to invest in the nightlife scene by purchasing The Cave Supper Club. However, his tenure was marked by inconsistent bookings and financial struggles, ultimately leading to the club's demise.

One serious setback was a disastrous booking of Ginger Rogers in 1978 that reportedly caused a $40,000 loss. Rogers was a legendary actress and dancer from Hollywood's Golden Age. At this point in her career though, she was no longer at the height of her fame, and her appeal didn’t resonate with the younger audiences.

That kind of financial blow, alongside the changing music scene, made it tough for The Cave to recover. By 1981, the old club couldn’t maintain the magic that had once drawn in huge crowds. That year it shut its doors bringing a close to its 44-year run.

Some folks blame an “identity crisis” for the Cave’s demise. It was caught between its older supper-club roots and the new era of disco or rock clubs and got left behind.

A short while later, The Cave was demolished, replaced by the Hong Kong Bank of Canada Tower. That might sound normal in a rapidly expanding city like Vancouver, but to many people, it felt like losing an important piece of the city’s cultural history.

Over the years since it closed, grieving fans of The Cave shared their stories in newspapers and online forums and groups as people tried to understand what The Cave meant and why it disappeared. Nostalgic recollections like how on certain nights, The Cave would be jam-packed for a performer like James Brown, who’d famously have someone wrap a cape around him to lead him offstage when he was “too exhausted to sing.”

Or more critical reflections on how attendance might drop if the headliner wasn’t well-known. Some local promoters told stories of how they tried to pitch punk or new wave acts, only to be shown the door.

Joey Keithley of the punk band D.O.A. once brought a tape of their song “Disco Sucks” to audition for The Cave. The owner cut it off after half a minute and suggested they “try disco,” then kicked him out. It seems The Cave was never sure how to handle that new generation of performers and that failure to get hip with the times led to its demise.

Some older Vancouverites still remember going there as teenagers (often sneaking in) to hear Ray Charles or Roy Orbison. Stories surface of parents bringing their kids along, or young couples who saved up for a special date night.

In its heyday, the club served as a place where people of different generations could share a love of music, or at least share a sense of adventure in that artificial grotto. At its height, even the fact that the cave décor was slowly crumbling had a certain appeal: “glitzy grunge,” as one person called it.

If you walk near 626 Hornby Street now, you won’t find any sign of the weird and wonderful cave that was. Instead, there’s modern construction and no real indication that such a lively, unusual venue once stood there.

That might feel disappointing, especially when you picture Ella Fitzgerald performing one week and Ike & Tina Turner the next. But while the building is gone, The Cave’s legacy endures in the memories of those who experienced it. And sometimes, it’s better to celebrate what once was rather than dwell on what’s been lost or changed as places evolve with new tastes and audiences.

Ask longtime Vancouver residents, and you’ll find that many had their first taste of world-class music or showbiz excitement there. It held on for 44 years—pretty impressive for a nightclub that started with papier-mâché stalactites.

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story:

https://vancouvertraces.weebly.com/the-cave-nightclub.html

https://www.setlist.fm/venue/the-cave-vancouver-bc-canada-33d490e5.html

https://montecristomagazine.com/community/the-cave-supper-club

https://www.vancouverisawesome.com/history/the-cave-supper-club-1938-1933744

https://evelazarus.com/tag/the-cave/

https://www.knowledge.ca/program/150-stories-shape-british-columbia/short/e66/cave

https://thebestlittlemoviehouseinvancouver.com/old-club-district/

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/vancouver-feature-doors-open-into-an-exotic-cave