RPM Magazine: How a Folded Legal Page Revolutionized Canadian Music

The unlikely story of how a former cop and a radio whiz kid fought for Canadian music to be played on Canadian radio

The room buzzed with nervous energy as Walt Grealis stacked the freshly mimeographed pages on a folding table. The chemical scent of ink hung in the air, mingling with cigarette smoke and percolating coffee. “Big Town Boy” played softly on an old record player in the corner.

Walt’s friend Stan Klees had given him the demo, and Canadian Shirley Matthews, whose voice now filled the room, was exactly the kind of talent Walt feared might never make it in the current climate of Canadian music.

It was February 24, 1964, and 500 copies of a modest publication—just four pages, folded legal-sized paper—sat ready for mailing.

After years of watching Canadian musicians struggle for airplay on their own country’s radio stations, he and his old high school buddy Stan Klees were finally going to do something about it.

As he sealed the last envelope containing the inaugural issue of RPM Weekly, neither Walt nor Stan could imagine that this humble stack of paper would eventually reshape the Canadian music industry, birth the Juno Awards, and help create the regulations that would finally give homegrown artists a fighting chance.

Hello again, today, I want to walk you through a fascinating slice of Canada’s musical past. It’s about RPM Magazine. The weekly publication that helped spark the rules we now call CanCon (short for Canadian Content).

If you’ve ever turned on the radio and heard The Tragically Hip, or marvelled that Sarah McLachlan and Shawn Mendes enjoy plenty of home-country airplay, you owe part of that to some determined people who, many years ago, believed in uplifting Canadian talent at a time when few others would.

What you’re about to read weaves together 1960s pop culture, an unlikely policeman-turned-publisher, and a group of music lovers who felt that, yes, Canadians should hear their own voices on the airwaves. So let’s head back to the early 1960s, when even some top executives in Canada’s record industry had little faith in local stars.

In the 1960s, English-Canadian pop music was largely overlooked. Sure, we had bright talents, people like Gordon Lightfoot, Paul Anka, and The Guess Who, but they had to knock on U.S. doors to get noticed.

Radio programmers and record label reps up here often said, “Why bother? The American hits are already dominating the charts.” If you picked up a local newspaper, you might see a piece like Jerry Ross’s 1964 headline: “Canada Has A Booming Record Industry (But Only Because It’s 95% American).”

That was the norm. Radio stations liked to fill their playlists with whatever had a proven track record in the States. And for musicians trying to make it in Canada, this was discouraging.

Many gave up, moved south, or changed careers entirely. It’s surreal to imagine this, especially because today we can rattle off big Canadian names like Shania Twain, Sarah McLachlan, Bryan Adams, and Avril Lavigne, who are heard everywhere.

But one man who refused to accept that sorry status quo was Walt Grealis. Born in Toronto on February 18, 1929, Walt grew up in a firefighting family. His background was a blend of Irish, Spanish, and Cree, so he had a deep sense of local pride and identity.

But music wasn’t even his first pursuit. Right after high school, he joined the RCMP (the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) and then switched to the Toronto police force when he was in his early 20s.

By 1957, he was ready for a new adventure and a break from policing. He took a job running sports and social activities at a Bermuda hotel, then returned home to do promotions for O’Keefe and Labatt’s breweries.

People who knew Walt back then said he could sell anything, and he never ran out of enthusiasm.

Eventually, in 1960, he landed a job in the music world at Apex Records. Apex was an Ontario distributor for an early Canadian record company (Compo), which later evolved into Universal.

From there he hopped over to London Records. He was good at coaxing radio DJs to give airplay to new singles of the Canadian acts on the labels he worked for. But he was infuriated by how little attention was given to homegrown music and how hard it was to convince Canadian broadcasters to play local talent.

During the early 1960s, Walt saw the lack of Canadian music on Canadian radio stations as a genuine crisis. According to one anecdote, it all came to a head when Walt was in a meeting with Harold Moon of BMI and a Buffalo radio DJ named George “The Hound” Lorenz.

Lorenz published a “tip sheet,” basically a list of promising new singles that radio stations should consider. In those days, if you had a tip sheet, you held real power over which songs got discovered. At that meeting, Lorenz suggested Canada could use something like his tip sheet, presumably meaning, “Go ahead and license or use my publication.”

But Walt took this as a sign that he should launch his own tip sheet rather than just taking the American’s tip sheet. He thought, “Why not create a Canadian industry resource that focuses on our own talent?”

So he reached out to Stan Klees, an old high school friend who was deep within the Canadian music industry and the two got to work at creating the first-ever northern tip sheet.

Born in 1932, Stan was a musical wonder kid who had started working at CHUM Radio when he was only 16 years old. Over the years, he started and co-owned a few labels, including Red Leaf Records, which had a notable 1965 hit (“My Girl Sloopy” by Little Caesar and the Consuls). But he faced the same frustration: DJs would toss out Canadian singles without even listening.

Stan crunched the numbers and told Walt that it might cost around $500 a week to start a weekly trade magazine. That seemed pretty steep though, so Walt hesitated. As much as he believed in the project, he couldn’t go bankrupt to give it a go.

But Klees was determined they could come up with something. That’s when he proposed a creative solution: use a legal-size page, run it off on a mimeograph machine, fold it, and you’d get four pages for much cheaper than printing individual pages.

A mimeograph was a low-cost duplicating machine used to produce multiple copies of documents. It worked by forcing ink through a stencil onto paper, a process known as mimeograph and was cheaper than running a printing press.

Invented in the late 19th century, the mimeograph was widely used in schools, offices, churches, and for DIY publishing before being replaced by photocopiers in the 1960s and 1970s.

That folded-up legal piece of paper seemed like enough space for basic stats and blurbs. Walt liked the idea and thought it just might fly.

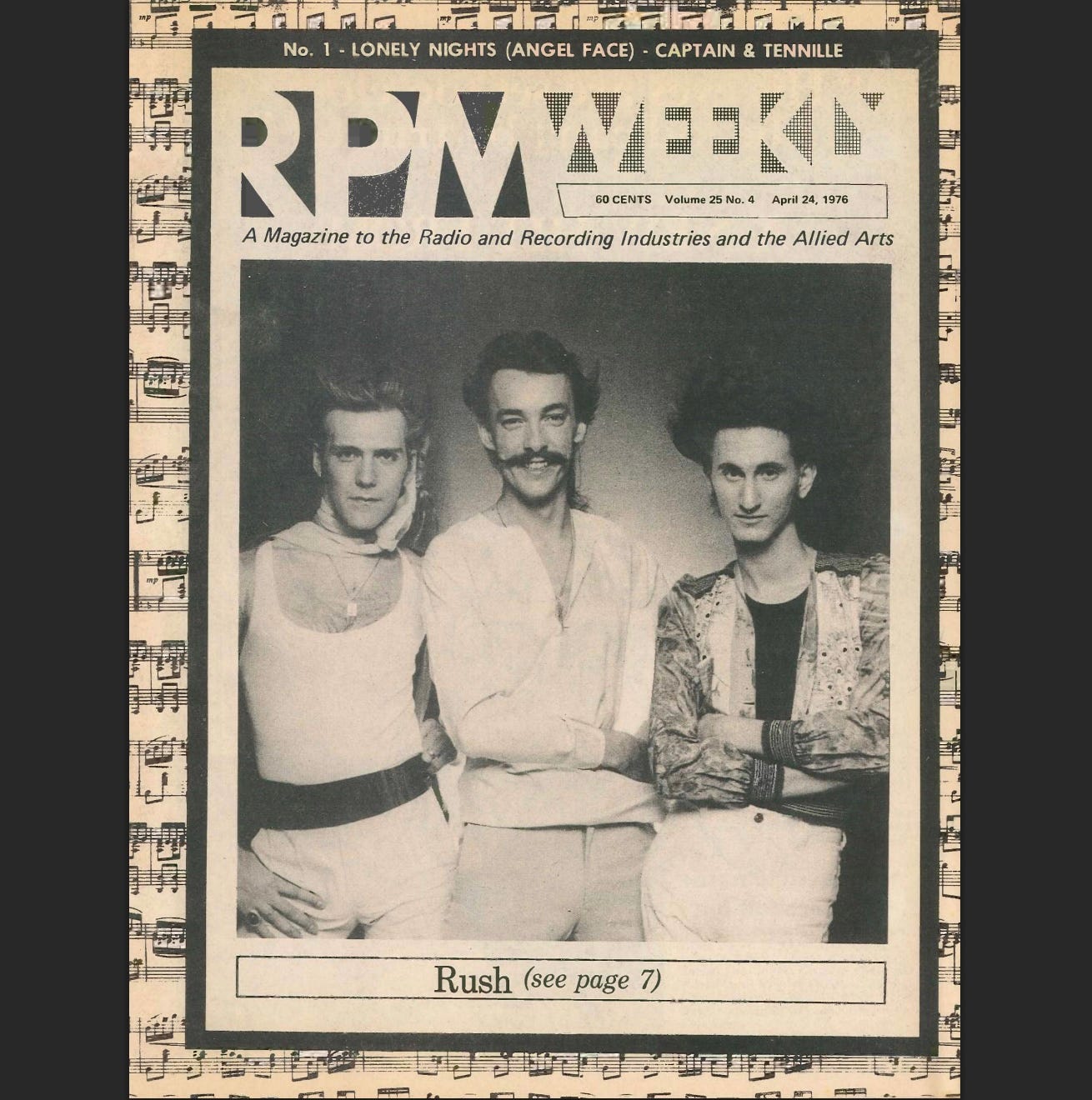

On February 24, 1964, the first 500 copies of RPM Weekly (short for Records, Promotion, Music) were mailed out—free of charge. Walt covered the content, while Stan contributed design ideas.

The hope was that someone, somewhere, would realize this small publication might be the best way to learn about Canadian music from coast to coast to coast.

At first, it was mainly a list of new recordings and maybe a little bit of editorializing. But slowly, it picked up steam and evolved into something much bigger and much more influential.

People say that from the start, RPM felt more like a critical mission to save the Canadian music industry, rather than a regular trade paper. Walt was determined to talk about every new Canadian single every chance he could get, whether or not it looked like a sure-fire hit.

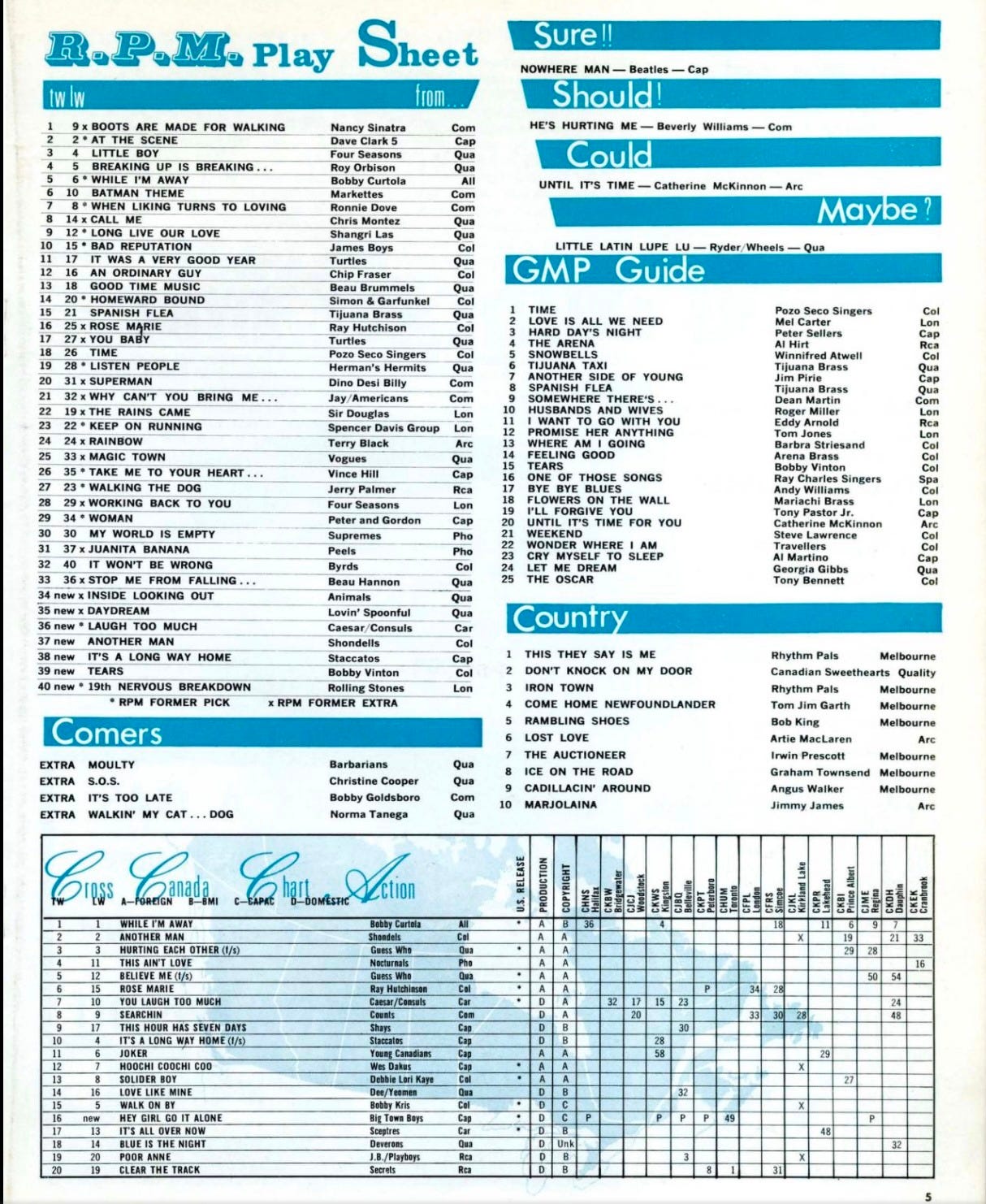

Together, Walt and Stan fuelled RPM’s evolution from a mere “tip sheet” to a true trade magazine with a national chart system. Canadian radio stations began contributing their local top tens, so RPM could compile what was actually happening here on our northern airwaves.

In March 1966, RPM introduced Canada’s Top Songs chart. For the first time, you could see a broad snapshot of Canada’s best-selling or most-played singles in one place. Previously the only reference point might have been the CHUM Chart in Toronto, but it didn’t really reflect the entire country.

As time passed, and the magazine’s popularity grew, record companies started to buy advertising space in RPM. This allowed Walt to expand from those four mimeographed pages to a slicker, more in-depth magazine.

RPM became the insider’s guide to who was recording, who was promoting, which DJs were adding Canadian singles to their rotation, and generated a new buzz about the Canadian music scene.

For artists, the magazine was a lifeline. It proved that there were folks who cared about building a real industry north of the border.

Stan and Walt had bigger dreams, though: they wanted to create a genuine “star system.” In other words, they wanted English-speaking Canada to rally behind its own artists, just as the francophone market in Quebec did so effectively.

They knew we needed more than just a magazine. We needed recognition ceremonies, promotional events, and an industry group to advocate for local acts on the national stage.

By the mid-to-late 1960s, they were already tinkering with ways to draw public attention to top Canadian artists. They launched an annual reader poll that singled out the year’s best local singer, best group, and so on.

It seemed like a small thing, but in an era where coverage was minimal, these poll results were golden. A mention in RPM’s poll gave an artist a ticket to local radio coverage, local press, and more.

To some outside observers, RPM was still a bit scrappy. The founding duo didn’t hide their partiality to Canadian labels. Some critics in the industry grumbled that RPM gave extra coverage to Stan’s Red Leaf Records.

But Walt and Stan never apologized. They insisted it wasn’t about favouritism—it was about levelling the playing field for local talent in a market flooded by American hits.

Regardless of any complaints, the magazine’s influence kept growing. Since 1964, RPM had conducted annual polls to award musicians in a variety of categories such as top male and female vocalist, and top Canadian record company.

As the ‘60s wound down, RPM felt that their awards were big enough to warrant holding its own annual awards ceremony rather than just printing a list of its annual award winners.

They called it the RPM Gold Leaf Awards. Its first inception was held in Toronto in February 1970, with a handful of winners, including singer Diane Leigh as the first-ever Gold Leaf recipient.

Stan Klees designed the awards which were intersting-looking walnut trophies shaped like a tall metronome. Meanwhile, in the background, Walt’s mother or maybe it was Stan’s mother—stories vary, but there’s a tradition that somebody’s mom made sandwiches to serve at the event. In other words, these early gatherings had humble beginnings, but don’t let that fool you because they were also groundbreaking.

Later that year, Pierre Juneau, the head of the Canadian Radio-Television Commission (CRTC), announced that Canadian radio stations would soon be required by law to air a certain percentage of Canadian music.

At first, everyone scrambled to speculate about “What’s considered ‘Canadian’?” or “How do we measure this content?” That’s when Stan Klees invented the now-familiar MAPL logo, which stands for Music (composer), Artist, Production (recorded in Canada), and Lyrics. If two or more of these four categories were Canadian, the single was considered Canadian content.

So as 1971 began, the official requirement kicked in: radio stations had to ensure that 30% of the songs they played were “Canadian” under the new MAPL system. This approach was part of a law that took effect on January 18, 1971, which forced station managers to include local records whether they initially wanted to or not.

Some station owners were furious and predicted doom and gloom as they railed against the government meddling in the industry to “control” the airwaves. To them, the feds had no place regulating what they played and many prophesized the move would lead to the downfall of northern broadcasting.

But RPM cheered. Walt wrote editorial after editorial about how these new regulations would finally give local artists a chance to be discovered at home. And he was right.

In casual conversations, folks began calling RPM’s stretched-metronome trophy (their Gold Leaf Awards) the “Juneau,” after Pierre Juneau. Because the awards happened the same year the CRTC devised the 30% CanCon legislation RPM, Walt Grealis, Stan Klees, and Pierre Juneau became linked in many people’s minds.

Pierre Juneau was a Canadian film and broadcast executive who played a pivotal role in shaping Canada's cultural landscape, particularly in music and broadcasting.

He was born on October 17, 1922, in Verdun, Quebec, which is now part of Montréal. Juneau grew up in a working-class family as one of five children; his father was a building materials salesman. After completing his education at the Université de Montréal, Juneau pursued further studies in philosophy at the Catholic Institute of Paris and the University of Paris.

It was during his time in Paris that he met Pierre Elliott Trudeau, who would later become Canada's prime minister. The two became close collaborators and co-founded the influential political and intellectual magazine Cité Libre upon returning to Montréal.

In 1949, Juneau joined the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), marking the start of a distinguished career in Canadian film and broadcasting. At the NFB, he advocated for greater representation of francophone filmmakers and played a key role in establishing a French-language production branch. By 1964, he had risen to become Director of French-language production at the NFB.

Juneau's early life and career laid the foundation for his later achievements as a cultural nationalist and policy leader who championed Canadian content regulations and public broadcasting. His work significantly influenced Canada's cultural identity and media landscape.

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) came about as a result of evolving broadcasting needs in Canada and the desire to regulate and promote Canadian content.

Its origins trace back to the early 20th century when concerns about foreign influence on Canadian broadcasting prompted the federal government to establish regulatory bodies.

The rise of private television and cable networks in the 1960s highlighted gaps in existing regulations, prompting Parliament to create an independent administrative tribunal with greater authority.

The Broadcasting Act of 1968 established the Canadian Radio-Television Commission (CRTC) and tasked it with implementing broadcasting policy, issuing broadcast licenses, and enforcing Canadian content quotas.

As the first chairperson of the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) from 1968 to 1975, Juneau was instrumental in implementing Canadian content regulations (CanCon).

Juneau's contributions extended beyond music. He also championed policies that ensured Canadian ownership of broadcasting networks and promoted homegrown programming on television.

His belief that "Canadian broadcasting should be Canadian" reflected his commitment to preserving and promoting Canada's cultural identity.

Soon the “Juneau Award” slang name was shortened to “Juno.” And that name resonated across the Canadian music scene. So much so that Walt and Stan decided to adopt it formally and in 1971 it officially replaced the Gold Leaf as the name for the national music awards.

By 1975, these Juno Awards were broadcast on CBC Television, reaching viewers across the country. By 1977, the newly formed Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (CARAS) took over the awards in an official capacity, but it’s important to remember that it all started with those humble RPM gatherings and Stan Klees’s original design for that walnut trophy.

And just like Walt Grealis had hoped, the CRTC’s rules were successful at giving local singles a fair shot at radio exposure. In many cases, it jumpstarted entire careers.

Singers who might have faded away suddenly found their songs getting spun on big-city stations. For example, it’s hard to imagine the success of certain 1970s and 1980s Canadian bands without that supportive framework.

Critics initially warned of “endless filler” from weaker acts. But behind the scenes, record companies began taking local recording sessions more seriously. With guaranteed radio play, it was finally profitable to develop Canadian artists.

RPM’s weekly columns documented the shift: the number of new Canadian singles and albums soared, and radio stations saw that plenty of these artists were, in fact, on par with their U.S. counterparts.

Throughout the 1970s, Walt Grealis used RPM’s pages to remind everyone that CanCon was not just about a quota. He felt it was the path to building a true music industry that could sustain itself.

To that end, RPM highlighted events like the Maple Music Junket, where musicians and industry reps travelled abroad to show the world that Canada had music worth hearing.

Another example was Canadian Music Week, which started as a simple RPM get-together called “Three Days in March” and eventually became a giant annual festival.

Bands that once struggled to get airtime in their own country were now regular fixtures on national playlists.

Take The Stampeders, for example. Their 1971 hit “Sweet City Woman” soared to number one in Canada and even cracked the U.S. Billboard Top 10. But before CanCon, that kind of exposure would have been extremely unlikely without a major American label behind them.

The Stampeders were signed to a Canadian label (Mel Shaw’s MWC) and recorded in Canada, exactly the kind of thing the new rules were meant to elevate.

Then there’s Burton Cummings, who had already seen success as the frontman for The Guess Who—a band that, thanks in part to early support from RPM and local radio airplay, became the first Canadian rock group to hit number one in the U.S. with “American Woman” in 1970.

That song predated the official CanCon rules, but the band’s continued success into the CanCon era was bolstered by consistent domestic airplay under the new regulations.

CanCon also helped pave the way for Anne Murray, whose breakthrough hit “Snowbird” in 1970 became a symbol of Canadian success. The song was one of the first Canadian singles to go Gold in the U.S., but more importantly, it got heavy Canadian rotation when CanCon rules kicked in. That helped make her a household name here at home.

And the list goes on: April Wine, Loverboy, Trooper, and Chilliwack all rose through the ranks in the 1970s and early 1980s, each benefitting from increased domestic airplay. Without that visibility in Canada, especially in major markets like Toronto, Vancouver, and Montréal, many of these acts might have remained regional curiosities or disbanded without ever gaining national traction.

By 1978, CBC’s The National reported that recording studios across the country were “booming,” and royalty payments to Canadian writers and publishers had quadrupled in just a few years.

That kind of industry growth doesn’t happen by accident. It was the direct result of local artists finally getting their foot in the door of their own country’s airwaves.

Beyond mainstream pop, RPM pushed for strong coverage of Canadian country music too. Their Big Country Weekend, launched in 1973, brought country artists together for panels and performances.

By 1975, it included the “Big Country Awards,” which evolved into the Canadian Country Music Association (CCMA) and its televised award shows. RPM didn’t just help pop and rock. Every genre found a champion in that little magazine.

Over the following decades, RPM added more niche categories: adult contemporary, dance, urban, and even charts for music videos once MuchMusic became a thing.

By the late 1990s, RPM had seen Canada’s music industry come of age. Acts like Bryan Adams and Shania Twain had proven that Canadian stars could hold their own internationally.

For his decades of dedication to Canadian music, Walt was honoured with the Order of Canada (1994) and inducted into the Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame (1999).

Meanwhile, the media landscape was changing. Advertising dollars were shifting toward online outlets, and music industry coverage was starting to fragment. Walt Grealis, by that point recognized as the “Godfather” of Canadian music promotion, was still running RPM.

However, the challenges of running a print magazine in the digital era grew serious. In November 2000, Walt announced that with ad revenues down and the old methods no longer sustainable, RPM would cease publication.

The final issue came out on November 13, 2000, closing the doors on one of the most important trade publications in the country’s music history. By the time the magazine shut down, RPM had published well over 9,000 different charts—leaving a giant historical record of what people in Canada were listening to over its 36-year run.

Sadly, Walt Grealis was diagnosed with cancer and passed away on January 20, 2004, at the home of his longtime friend and business partner, Stan Klees.

As a final tribute, the Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award was created by The Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences to spotlight people who have advanced Canadian music behind the scenes. Fitting for a man whose greatest triumph was championing others.

Stan Klees passed away in September 2023 at the age of 91, marking the end of an era. Together, he and Walt set the stage for what the Canadian music industry is now: a place where local singers, producers, songwriters, and label owners can thrive without having to relocate to the States.

That's the essence of RPM's story. It's not just a publication that printed charts. It was a magazine by people who believed this country's talent deserved a place on radio playlists from Halifax to Vancouver.

When you tune in to a radio station today and hear Canadian artists like The Weeknd dominating global charts, Alessia Cara winning Grammy Awards, or Arkells selling out arenas nationwide, you're witnessing the long-term impact of those decisions made in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Without the groundwork laid by RPM and CanCon regulations, would Justin Bieber have found his initial audience at home before conquering the world stage? Would bands like Our Lady Peace, the Barenaked Ladies, or Arcade Fire have received the early Canadian airplay that helped launch their international careers?

The modern Canadian music ecosystem—with its robust festival circuit, diverse indie labels, and global superstars—stands on the foundation that Walt Grealis and Stan Klees helped build.

Today's streaming platforms may have changed how we discover music, but the principle remains the same: Canadian artists deserve to be heard by Canadian listeners first and foremost.

The next time you see a Canadian win a Juno, or spot a rising star on CBC Music's searchlight competition, think of those four mimeographed pages from 1964, which helped make it all possible.

For me, the biggest takeaway is how a few determined champions can light a path for everyone else. Walt Grealis and Stan Klees took an unpopular stance: betting on Canadian music when most were sure it was second best, and they turned it into a vital piece of Canadian culture. One that continues to evolve and thrive in today's digital landscape.

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story:

https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/films-videos-sound-recordings/rpm/Pages/rpm-story.aspx

https://cjc.utppublishing.com/doi/10.22230/cjc.2005v30n3a1549

https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/films-videos-sound-recordings/rpm/Pages/rpm.aspx

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/rpm-emc

https://www.cbc.ca/archives/cancon-junos-radio-music-industry-1.6050466

https://web.archive.org/web/20070927021800/http://www.rrj.ca/issue/2002/spring/369/ https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-All-Music/RPM.htm

https://junoawards.ca/blog/a-man-a-magazine-and-a-mission/

https://www.socanmagazine.ca/news/socan-grieves-the-loss-of-stan-klees/

A well-researched piece that highlights the role of trailblazers like Grealis and Klees. Thanks for writing! It’s inspired me to dig deeper into this history.

Fabulous write-up on CanCon evolution!! Brought back a lot of great memories of the 60s-80s in particular. So many excellent musicians were trying to make it in the entertainment field - you needed some additional way to make money, or be fed at the pubs, restaurants, where you played. Challenging back then. Well, still challenging for different reasons...