The Canadian Music Teacher Who Rescued 3,228 Syrian Jews

How Judy Feld Carr built a secret network that saved an entire community from Assad's Syria

It’s past midnight in Aleppo, Syria, circa 1985. In the dank courtyard of Aleppo’s central prison, a Jewish prisoner named Zaki Shayu is being led, blindfolded, toward a waiting vehicle. Zaki’s mind races.

For four years, he has known only darkness, pain, and despair in this prison. Arrested in the early 1980s for attempts to help Jews emigrate, he has endured torture so severe that at one point the authorities even told his family he had died, to dissuade further inquiries.

But tonight something different is happening. No interrogation, no beatings. Instead, a guard murmurs to him, “Don’t speak. Do exactly as told if you want to live.” Zaki feels the night air on his face as he’s pushed into a car.

Unbeknownst to Zaki, Canadian Judy Feld Carr’s network has been working for months on his case. Through a combination of bribes to high-ranking officers and officials, a deal was struck: Zaki would be secretly released from prison and quietly expelled from Syria.

The car with Zaki drives through the silent streets of Aleppo. After years in a cell, the passing city lights and open sky seem unreal to him. He is taken to a safehouse where he is cleaned up and given civilian clothes and forged papers.

A handler briefs him: “You are no longer Zaki. You never existed here. In a few hours, you will be driven north. Do not try to run. Do not speak to anyone.” Zaki, still in shock, nods.

Just before dawn, Zaki finds himself in the back of a truck heading towards the Turkish border. Every bump on the road jostles his aching body, but with each mile, the air smells a bit sweeter: the scent of freedom.

The truck halts near a border outpost. Armed Syrian border guards approach, flashlights cutting through the darkness. Zaki’s heart nearly stops. One guard circles to the back of the truck and pulls open the canvas flap. He shines a light on Zaki’s face. Zaki stares down, avoiding eye contact.

For what feels like an eternity, the guard scrutinizes him against the photo in the paperwork. Then, with a curt motion, he returns the papers and signals them through. That guard, too, has been paid off as part of the intricate arrangement to let this prisoner vanish out of Syria.

By sunrise, Zaki Shayu steps out of the truck on the Turkish side of the border. He is met by an operative working with Judy’s network (possibly an Israeli contact or a local Jewish fixer). Within days, Zaki is on a flight out of Turkey.

Ultimately, he makes his way to Israel, where the Syrian Jewish community embraces him and helps him recover. He made it out alive. But there are so many more Jews stuck in Syria, desperately trying to escape.

Desperately hoping that the rumours of a Canadian woman known only as “Mrs. Judy” is real, and that she will somehow find a way to get them out too.

Hello there. Thank you for joining me for this story about a remarkable Canadian who saved more than three thousand people trapped under a hostile regime.

We’re focusing on a hidden chapter in Canadian history that unfolded in the shadows of Syria’s tight surveillance. As you read, I invite you to picture a Toronto mother of three quietly engineering escapes, phone call by phone call, bribe by bribe, until an entire community was freed.

Let’s dive in.

To understand why someone in Toronto would risk so much, we first need to know who was trapped and why.

If you’re already familiar with the history of Jews in Syria, feel free to jump ahead to the story of Judy Feld Carr by: clicking here. But if you’re like me and didn’t grow up learning about this part of the world, here’s the background that helped me better understand what she was up against.

Jews had lived in Syria for well over two thousand years. Legends claim the earliest arrivals might have journeyed there around the time of King David. By the Roman era, thousands of Jews thrived in big cities like Damascus and Aleppo.

Throughout their time in Syria, Jewish families built schools, prayed in storied synagogues, and studied precious manuscripts, like the Aleppo Codex.

The Aleppo Codex is a handwritten copy of the Hebrew Bible, dating back to around 930 CE. It was written by scribes known as the Masoretes, who were based in the city of Tiberias in what is now Israel. Scholars consider it to be the most authoritative and precise version of the Hebrew Bible. After it found its way to Syria, it was treated as a sacred treasure, placed in a synagogue vault and protected by Jews.

More Jews arrived in Syria after they were expelled from Spain in 1492, and for a long while, they lived in relative safety there.

For centuries, Syria was ruled by the Mamluk Sultanate, a powerful Islamic empire based in Cairo. The Mamluks controlled much of the eastern Mediterranean, including Egypt, Palestine, and Syria.

In 1516, the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Selim I launched a military campaign against the Mamluks. At the Battle of Marj Dabiq, the Ottomans crushed Mamluk forces and swiftly took control of Damascus, Aleppo, and other Syrian cities.

Syria remained part of the Ottoman Empire for over 400 years. It was divided into provinces (called “vilayets”), including Damascus, Aleppo, and Beirut.

The empire allowed some religious minorities, like Jews and Christians, to live under the “millet system,” which gave them limited autonomy in exchange for extra taxes and second-class status.

Life was often hard, but Jewish communities survived, especially in Syrian cities like Aleppo, Damascus, and Qamishli. If you were around in the early 1900s, you would have seen big Jewish communities in major Syrian cities, made up of people who had strong connections to their Syrian homeland but followed their own traditions.

Syria stayed under Ottoman control until World War I, when the Ottomans lost and the region of its Arab provinces was handed over to France under the “French Mandate.”

Instead of granting these regions independence, the League of Nations (which was the precursor to the United Nations) handed out “mandates,” which were essentially colonial-style permissions, to European powers to govern these territories.

France was given the mandate for Syria and Lebanon. Britain got Palestine and Iraq.

The French Mandate in Syria lasted from 1920 to 1946. During that period, France ruled Syria with a mix of military force, political maneuvering, and divide-and-conquer tactics.

They divided Syria into smaller regions, like separate states for Alawites, Druze, and others, hoping to keep ethnic and religious groups from uniting against them. But Syrians resisted French rule fiercely, sparking several revolts (most famously the Great Syrian Revolt of 1925–1927).

France cracked down hard by mounting a campaign of bombings, arrests, and stricter control.

During the French Mandate, Jews in Syria did not have full equal rights but generally fared better than under later regimes. That said, European fascist ideas—especially Nazi antisemitism—started to influence local politics in the 1930s.

Syria saw a rise in European-style nationalism, and fascist and Nazi ideas began to circulate.

During this time, Nazi Germany actively influenced parts of the Arab world, including Syria, through Arabic-language radio broadcasts and literature promoting antisemitism and anti-Zionist ideas.

While Nazi propaganda and antisemitic literature did circulate in parts of the Arab world—including Syria—it’s important to note that many Arabs did not support these views, and some even protected Jews during times of persecution.

France itself was divided back then. In June 1940, Nazi Germany invaded and defeated France in just six weeks. France surrendered, and the country was split into two zones: Occupied France – controlled directly by Nazi Germany, and Vichy France, a so-called “free zone” in the south, governed by a French regime based in the town of Vichy, led by Marshal Philippe Pétain.

The Vichy government was technically “independent,” but in reality, it collaborated with the Nazis, and followed Nazi policies, including antisemitic laws.

Even though Syria was thousands of kilometers away, it was part of the French colonial empire. So when France surrendered in 1940, its overseas colonies, including Syria and Lebanon, fell under the control of Vichy France.

That meant Nazi-aligned policies came into effect in Syria too. Antisemitic laws were passed in Syria under Vichy rule. Jews were banned from many jobs, public offices, and schools, much like in Nazi-occupied Europe. Jews were also denied basic rights such as owning telephones or driver’s licenses.

Jewish life in Syria became even harder, despite it being far from the European front lines.

In 1941, Britain and the Free French forces (led by General Charles de Gaulle) launched a military campaign to take back Syria from Vichy control. They succeeded, but only after a bloody few months.

In 1944, the Jewish Quarter in Damascus was attacked by mobs. One of a series of attacks that showed that antisemitism wasn’t going to go away any time soon.

Syria gained its full independence in 1946, after World War II. But the seeds of political instability, religious tension, and authoritarianism had already been planted during the French Mandate.

In nearby Palestine, the period of British rule following World War I was very turbulent. Violent clashes between Arabs and Jews and revolts happened frequently. Britain found itself stuck in the middle, unable to satisfy either side.

By 1947, the situation was out of control. Britain was broke from WWII. British soldiers were being killed by Jewish underground groups fighting for independence. Arab-Jewish tensions were regularly exploding into violence. Britain called in the UN for help as it planned to make an exit.

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly voted to adopt Resolution 181, which proposed a plan to partition British-controlled Palestine (next door to Syria) into two separate states: one Jewish and one Arab, with Jerusalem placed under international control.

This is what is referred to as the UN Partition Plan. The land was to be divided as such: the Jewish State would cover 56% of the land, the Arab State: 43%, and Jerusalem around 1%, to be governed by the UN as a neutral international city.

The plan acknowledged that both Jews and Arabs had deep historical and religious ties to the land, and that the British mandate over Palestine (which had lasted since World War I) needed to end with a long-term solution.

The Jewish leadership in Palestine (represented by the Jewish Agency) accepted the plan, even though the proposed borders were far from ideal and cut off access to some historic or strategic areas.

The Arab leadership in Palestine and all surrounding Arab countries, including Syria, flatly rejected it. They argued it was unfair to give so much land to a Jewish state when two-thirds of the population of Palestine at the time was Arab.

They also opposed any recognition of a Jewish state, seeing it as a colonial-style imposition after years of European Jewish immigration into the region. For many Arabs, especially Palestinians, the plan felt like an outside-imposed solution that ignored their rights to self-determination and the land they had lived on for generations.

Almost immediately after the UN vote to partition Palestine, violence broke out between Jewish and Arab communities there. Anti-Jewish riots also broke out in other cities in the region, like Aleppo, Syria (1947), just days after the UN vote.

Then, after Israel declared independence on May 14, 1948, Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon invaded the new state. This became known as the 1948 Arab-Israeli War (or the War of Independence in Israel, and the Nakba or “catastrophe” in the Arab world).

In Syria’s eyes—and in much of the Arab world—Zionism was seen as a colonial project imposed by the West. When Israel was created, it was seen not as a homeland for Jews, but as a Western-backed invasion.

In some Arab countries, governments responded not only by going to war with Israel but also by enacting harsh policies toward their own Jewish citizens.” Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and others started seizing Jewish property, revoking citizenship, and banning emigration.

Across the region, Jews were collectively blamed for what was seen as the loss of Arab land. Many Arab countries refused to recognize Israel, and those who went to war with it (including Syria) suffered a humiliating defeat.

In the aftermath of the war, frustration and anger over defeat and displacement were, in many cases, directed inward toward long-standing Jewish communities that had no role in the conflict.

Jews in Syria (and Iraq, Egypt, Yemen, etc.) were accused of being traitors, spies, or Zionist collaborators, even though they were long-established communities with no direct connection to the fighting in Palestine.

After Israel’s creation in 1948, Syria banned Jews from emigrating, fearful that they would go to Israel and strengthen its population. Jewish property was seized, bank accounts frozen, and people were banned from certain professions that would give them any influence on people or the government.

Jews were treated less like citizens and more like bargaining chips, restricted in every aspect of life and unable to leave, as if being kept in reserve for potential political use.

In 1949, an attack on the Menashe Synagogue in Damascus killed 13 and wounded 32. In the 1950s, a special road was even purposely built straight across an old and sacred Jewish cemetery, as if to announce: “You have no place here.”

Eventually, Jews couldn’t travel beyond their own neighbourhoods without a permit. Large amounts of money, sometimes called “departure ransoms,” were demanded if someone tried to emigrate. And if you were caught sneaking out, the punishment could be prison or death. Many decided to flee anyway. Some succeeded, while others were imprisoned, beaten, or killed on the spot.

In 1970, General Hafez al-Assad seized power in Syria. His regime used every possible tactic to keep the remaining Jews pinned down. Telephones continued to be banned and confiscated to prevent Jews from reaching the outside world.

Jewish doctors lost their jobs. Secret police watched synagogues and wedding halls. Reports also mention dreadful incidents, like that of four young Jewish women who tried to escape and were brutally murdered.

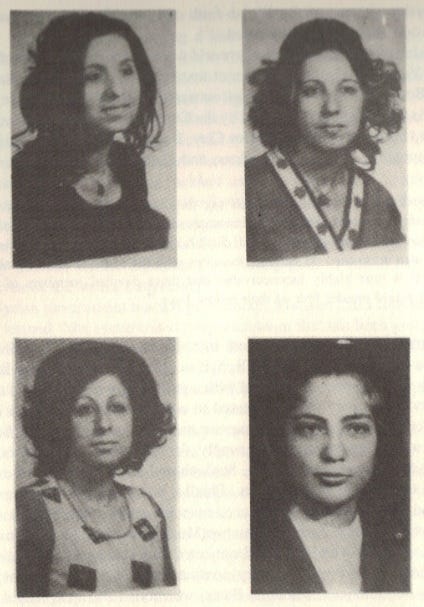

In March 1974, Eva Saad and three sisters, Lulu, Mazal, and Farah Zeibak, also recorded as Toni, Laura, and Farah Zebah, paid smugglers to help them escape from Syria across the Lebanese border.

Their bodies were discovered in a cave near the Lebanese border. They had attempted to flee Damascus with the help of paid guides, who instead raped, robbed, and murdered them.

The smugglers then mutilated the bodies—some reports say with acid—and buried them in the cave. When they were eventually recovered, their remains were returned to their families in sacks. In the same cave, the bodies of two young men who had tried to escape earlier were also found.

This atrocity sent shock waves through the community. In a rare act of public protest, 1,000 Damascus Jews, joined by sympathetic Christians, demonstrated in the streets against the murders and the ongoing oppression.

It was a brief moment of outcry in a decades-long silence. The Assad regime officially blamed criminal smugglers for the crime, but many suspected the hand of Syrian agents in the gruesome fate of those victims. The message to Syria’s Jews was unmistakable: attempting to leave could be a death sentence.

With the region’s politics driving clampdowns, the Jewish population in Syria started dropping. Some made it out through bribes or smuggling. Others simply lost hope. One survivor described it bluntly: “We lived in an open-air prison.”

Before 1948, Syria had been home to between 15,000 and 40,000 Jews, depending on the year and the source. These were ancient communities with roots stretching back more than 2,000 years, especially strong in Aleppo and Damascus. But after the creation of Israel and rising hostility in the region, thousands fled or were driven out, leaving only a small remnant behind by the 1970s.

By the mid-1970s, Syria’s once-thriving Jewish population had been reduced to just a few thousand people, possibly as few as 4,000. Some estimates are lower, depending on whether they counted individuals or families. Either way, the community was a shadow of what it had once been.

The remaining Jews were now concentrated in just three cities: Damascus, Aleppo, and Qamishli. They were forbidden to live anywhere else.

Now, how does an Ashkenazi Jewish Canadian music teacher fit into this scene?

Her name is Judy Feld Carr. Born in Montréal in 1938 and raised in Sudbury, she eventually settled in Toronto.

Feld Carr earned multiple music degrees from the University of Toronto, including a Bachelor of Music in music education and two Master of Music degrees, in musicology and music education.

By the early 1970s, she was in her mid-thirties, living a normal Canadian life with her husband, a physician named Ronald Feld, and their three children. She taught high school music in Toronto and she and her husband were socially conscious and actively involved in her synagogue community.

Although they had no direct ties to Syria, they were also deeply committed to helping her fellow Jews, no matter where they lived. They were moved by Jewish causes and the principle that “Whoever saves a life… it is as if he saved an entire world.”

One day in 1972, she came across a newspaper article in the Jerusalem Post describing the horrors facing Syrian Jews.

Reports of minefields, murders, and families living in constant terror haunted her. In particular, one story of tragedy stood out: twelve young Syrian Jews had been killed attempting to escape – reportedly mutilated by a minefield near Qamishli.

The article struck a nerve. Judy and her husband Ronald were “appalled at the plight” of these Jews and felt they had to do something.

At first, they started small. Together, they formed a local committee in their synagogue, Beth Tzedec, to help Jews in Arab regions. Their idea was to try to make contact with the community in Syria to offer moral and material support, things like prayer books or Hebrew texts.

Getting any parcel into Syria was tricky because the al-Assad regime censored everything. But Judy and her husband were committed to figuring out a way.

Incredibly, they managed to get a phone number for a Jewish family in Damascus. The husband, it turned out, worked for the Syrian secret police, possibly one of the only Jews still employed by the state.

Judy made the call herself, fully aware of the risk it posed not to her, but to the people on the other end. She later described it as the only phone call to Syria she ever dared to make. To her astonishment, the man answered and didn’t hang up. He even gave her the contact details for the Chief Rabbi of Damascus, Rabbi Ibrahim Hamra.

That call opened a door. Judy immediately sent a prepaid telegram to Rabbi Hamra asking if the Jews in Damascus needed any Hebrew religious books. A week later, a reply came with a list of requested titles. Thrilled and anxious to keep this channel open, Judy gathered the books and carefully stripped out any pages that identified Israeli publishers (to avoid Syrian censorship).

Inside each cover, she inscribed a message: “Best wishes to the Jewish community in Damascus, from the Jewish community in Toronto, Canada.” Then, in a clever move, she laid a $50 bill on top of the stack inside the shipment.

The bribe was intentional: if Syrian customs opened the box, they would likely pocket the cash and still deliver the books. This small act of “greasing the wheels” worked, and the books reached Rabbi Hamra. It was the first successful link made between Judy’s group in Toronto and Jews in Syria.

Thus began an extraordinary correspondence carried on in coded language. Aware that Syrian censors might read any direct letters, Judy and Rabbi Hamra devised a code using references to Biblical verses and Talmudic references to convey messages beyond just book requests.

For example, a quote from Psalms or an obscure Talmud section might indicate something about a family needing help. Over time, this code allowed Judy to learn about the dire situation in Damascus without tipping off the authorities. Bit by bit, she realized the full extent of how trapped Syrian Jews were.

The “book exchange” expanded: within a few years, Jews in Aleppo and Qamishli joined the secret communications network. Judy was essentially operating an underground lifeline via mail, in which innocuous religious packages carried desperate pleas for help.

Then the unimaginable happened: in 1973, Ronald died suddenly of a heart attack. Thirty-three-year-old Judy was left with three young children to care for and had every reason to step back from her volunteer projects.

But she couldn’t let go. She felt a mandate to keep going in Ronald’s memory. Her Toronto synagogue established a fund named for him, which started channelling donations to support Jews in Arab Lands.

This fund started attracting private donations from across Canada and the U.S., and would become the economic engine for what was to come.

By 1975, Judy had a foundation of contacts and a trickle of funding. What started as a relief mission: sending books, medicines, and holiday supplies, was about to transform into a full-fledged rescue operation.

Then she received a secret letter, smuggled out by an Aleppan Canadian who had visited family in Syria but was arrested by Syrian authorities and held for weeks before finally being released and returned to Canada.

When the woman arrived back in Canada, she sought out Judy and handed her a letter that she had hidden in her clothing. “It’s a letter that you only see during the times of the Holocaust,” Judy recalled.

The letter read, “Our children are your children. Get us out of here!” Three Aleppo rabbis wrote that desperate plea, likening their situation to the days of the Holocaust.

That letter was Judy’s turning point. Mailing books or small donations was not enough. The Jews of Syria were crying for rescue, and Judy decided to free people one at a time, if that was what it took.

Picture yourself in Judy’s position. You’ve never done anything remotely cloak-and-dagger in your life. You’re a music teacher and a single mother. Yet you’re being asked to somehow get prisoners out of a Middle Eastern dictatorship. Where do you even start?

In late 1975, an opportunity presented itself. Judy heard of an Aleppan rabbi, later identified as Rabbi Eliyahu Dahab, who was gravely ill with cancer and locked in prison, having been tortured because two of his children escaped Syria.

One of his relatives in Toronto reached out to Judy, pleading for her to somehow get the rabbi out for medical care.

She had no training in rescue operations or espionage, but she felt a moral obligation. She started calling contacts, raising funds quietly, and using her synagogue’s network to pass money across international borders. As one donor would later say, it was basically “buying a life.”

Syria’s bureaucracy was corrupt. Nearly anyone with influence could be bribed: secret police officers, judges, passport clerks, and border agents. Judy raised the ransom money bit by bit, then used local go-betweens inside Syria to negotiate a release for the rabbi. She had to make sure all the necessary officials were paid, so no one on the ground would block the rabbi’s extrication.

It took a year and a half of negotiations, but finally in 1977, the unbelievably frail rabbi, emaciated, terminally ill with cancer, and bearing scars from torture, was allowed to fly out of Damascus under the pretext of receiving medical care abroad. Success.

He arrived in Toronto, and Judy personally took him to the hospital. Even though he was near death, the fact that he had made it out of Syria felt like a small miracle. He broke down in tears the first time a nurse greeted him in Hebrew.

It was a moment Judy never forgot. Even though this victory came late in the rabbi’s life, it was a victory all the same. He then made one last request: he wanted to see his mother in Jerusalem. Judy arranged it, and days later, he passed away in Israel, finally reunited with his family as a free man.

Of her first successful campaign, Judy would later say, “It took ages to do it… I didn’t know what I was doing. I mean, I am a musicologist, not a rescuer.” But sheer determination filled the gap in formal training.

During that difficult mission, Judy realized that what seemed impossible could actually be done: one could, through bribes and cunning, pry open the iron doors of Assad’s Syria. That realization launched a clandestine rescue network that would grow and operate for nearly three decades.

After saving Rabbi Dahab, Judy told herself: “If we can do it for one, why not more?” She still had a small amount of funds coming in through her synagogue’s memorial fund. She also now had a small group of trusted donors in Canada and the United States.

The key was to keep it secret.

If the Syrian government, or even local criminals, found out about the money and the plan, it would put everyone in danger.

So, Judy set up a cautious chain of contacts both in Syria and outside. Some of the folks in Syria were Jewish community members who kept low-level connections with authorities. Some had relatives in government offices or in the secret police.

Some professional smugglers knew how to guide people across the border into Turkey or Lebanon. This meant forging documents, planning out desert or mountain routes, and timing each step carefully and covertly to avoid patrols.

When bribery was possible, Judy would try that route first. She learned how to invent plausible excuses for travel: a sick grandmother abroad, a business trip, a wedding invitation. Syrian officials would demand bribes at multiple stages, plus a large bond to make sure the person would return.

Of course, they never returned, and the officials pocketed the money. But that was part of the unspoken deal. Once a Jew had a valid exit visa and was escorted through security at Damascus airport, that Jew was essentially free to land in a safe country, often Canada or the United States, and quietly head to Israel or another final safe destination.

Not everyone could be rescued by bribes only though. For those in imminent danger of arrest, or those who faced special hostility, Judy turned to smuggling.

She paid for vehicles, forged papers, and arranged safe houses near borders. The most common route was into Turkey to the north (a border relatively close to Qamishli and Aleppo). Another route was into Lebanon, though the Lebanese border was heavily patrolled and complicated by Lebanon’s civil war in the 1970s–80s.

A few even escaped via Jordan or by sea out of Lebanon. These journeys were terrifying. Families sometimes travelled in battered cars or hiked through rough terrain at night.

They relied on local guides who might switch sides if a higher bribe appeared or if it was needed to save themselves. Yet in all the years Judy coordinated escapes, she never lost a single person.

This almost unbelievable record speaks to the caution, planning, and perhaps luck that accompanied her work. Oftentimes, she had to split up families for escapes. Parents might send their children first, or vice versa, hoping to reunite later in freedom.

The secrecy Judy maintained throughout all of this was astounding. She never announced fundraising campaigns in public. She never told most donors the details of how their money was used. She simply told them, “We’re helping Jews in trouble. Trust me.” And they did.

Some in the Canadian Jewish community suspected something major was happening behind closed doors, but they knew to keep quiet. Even the Israeli Mossad, which also smuggled Jews out of Syria, had little direct involvement with Judy at first.

She remained an independent operator with no government safety net. This was dangerous for her, but she believed it reduced the risk of drawing attention. Remarkably, she kept her circle extremely small: “Only she knew the details” of her network, one account notes.

For those trapped in Syria, the name “Mrs. Judy” was passed around in hushed tones. If you had a relative abroad who found Judy, you had hope. If no one knew about her, you might never even learn that a rescue network existed.

Judy never contacted people inside Syria first; she let them approach her, or their families did. That way, she avoided infiltration and also respected people’s own decisions about whether to risk an escape or not. She never wanted to be in a position where she was pressuring someone to go.

Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, Judy continued this work while raising her children and even serving as president of her synagogue. She remarried in 1977 to Donald Carr, a lawyer, blending their families to have six children at home.

It is astonishing to consider that by day she was a school teacher and community volunteer, but in the shadows she was negotiating with Syrian intelligence agents and smugglers.

She later admitted, “I was going to quit almost every second day, but I couldn’t, because… I had people depending on me. And all they knew was that their way out of the country was ‘Mrs. Judy in Canada.’ It was hard, but I had no choice.”

Let’s walk through a few more rescues Judy handled, just to give you an idea of the scope of what she accomplished, what she was up against, and what it was like for the people she helped.

One story took place in the mid-1980s, involving a man named Zaki Shayu. He had been imprisoned in Aleppo for four years for aiding Jewish escapes. He was tortured so badly that the authorities told his family he was dead. Meanwhile, Judy’s contacts learned he was still alive, but near death in a prison cell.

Judy quickly arranged for a series of bribes to high-ranking officials. The plan was to have Zaki “quietly released” so there’d be no public embarrassment for the regime.

One night, guards hauled him out of his cell, blindfolded him, shoved him into a car, and drove him to a safe house. When the blindfold came off, they told him: “You’re being expelled, but officially you’re dead.” Then they smuggled him across the border into Turkey at dawn.

A few days later, Zaki reached Israel.

Years later, Zaki Shayu would speak publicly about his ordeal. Describing four years of horrific torture in a Syrian jail. He would also learn who was behind his liberation. In a moving encounter at a seniors’ event in Bat Yam, Zaki told an audience about his experiences, not realizing that Judy Feld Carr was sitting in the room.

When asked how he got out of Syria, he said, “There was a lady in Canada. Her name was Judy.” At that, Judy’s husband leaned over and revealed, “She’s right here—she’s my wife.” Zaki’s eyes widened; he rose and embraced Judy to grateful applause and tears from everyone present.

The woman he never met during his escape, who operated from thousands of miles away, was finally real to him. It was a powerful full-circle moment: the once faceless “Mrs. Judy” from coded whispers was now a flesh-and-blood friend, sharing in the joy of his freedom.

Another time, Judy arranged an escape for a mother, Miriam, and her six children on a moonless night in 1989. Miriam’s husband had already been arrested on bogus charges. Judy got word that the police might come for the rest of the family next.

She paid a local Muslim smuggler to drive them near the Turkish border. They endured multiple checkpoints in terrible weather, bribing guards along the way.

As the car moved toward the outskirts of Damascus, Miriam silently reviewed the plan in her head, as instructed: They will pose as rural villagers going to visit relatives near the Turkish border. The children have been told to stay absolutely quiet. Any whimper could attract attention at checkpoints.

At one point, headlights appeared behind them, and the smuggler doused the lights and turned onto a side path to hide. Tension soared. But, eventually, just before dawn, the family slipped across the border on foot.

They would soon catch a flight to freedom.

Judy remembers this rescue in particular because it happened on the very day of her father’s funeral in Toronto. She actually postponed the funeral for an hour to finalize the arrangements, then she sat in shiva (the Jewish mourning period) while checking her phone for updates.

During that entire mourning week, she remained on edge. At the end of shiva, she received the call: “They made it out.” She later admitted, “When you are buying somebody’s life, it can be horrible,” but moments like that phone call made it worthwhile.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Syria’s government kept a tight lid on Jewish departures, but international pressure built steadily. The United States and various Jewish organizations complained about human rights abuses.

Figures like Senator Frank Lautenberg and then-Senator Al Gore highlighted Syria’s treatment of its Jews.

Meanwhile, Hafez al-Assad sometimes let a few Jews leave to improve his image. He allowed young women to emigrate if they were going to marry Syrian Jewish men abroad. But it was always on Assad’s terms, and the families left behind remained vulnerable.

Then came the early 1990s. After the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference, Syria entered peace talks with Israel, with the U.S. acting as broker. Under intense pressure, the regime lifted many travel restrictions for Jewish residents.

Officially, they were still forbidden to go to Israel, so many traveled first to the United States, Turkey, or Europe. Soon after, they quietly hopped over to Israel or joined Syrian Jewish communities in Brooklyn or elsewhere.

In 1994, there was a coordinated effort to get more than a thousand Syrian Jews out. By the mid-1990s, the once-large communities in Aleppo and Damascus had nearly emptied.

Families who had lived there for centuries said goodbye, sometimes turning the keys to their homes over to neighbors or distant relatives. Of course, Judy’s secret pipeline had already been working for two decades, so some of these families had gone out earlier with her help. Others waited until restrictions eased.

Judy’s underground mission didn’t officially wind down until 2001. That year, on September 11, a family boarded a plane from Damascus to New York City with Judy’s assistance. They landed at JFK Airport just one hour before the terrorist attacks occurred.

As events in New York and Washington, D.C., shook the world, Judy got confirmation that this final group had arrived safely. It was a surreal closing to her 28-year campaign.

All in all, Judy estimates she personally rescued or ransomed 3,228 Jews from Syria. That number doesn’t count those who left after official restrictions lifted, nor people rescued by other groups like the Mossad.

Yet her private network was essential for the darkest period, especially in the 1970s and 1980s. By the time she stepped away in 2001, fewer than a hundred Jewish people chose to remain in Syria, mostly older individuals who preferred not to uproot their lives.

Over time, Judy’s story became public.

In 2001, the same year she ended her work, she received the Order of Canada, the country’s highest civilian honour. She also earned distinctions from Israel and other organizations.

Newspapers described her as a “Canadian housewife turned rescuer,” though she humbly insisted she was just a music teacher who fell into this role. She’s been featured in documentaries and written about in books, but she’s never boasted about it. For her, the real reward was seeing a community survive.

Some of the personal tributes to Judy are especially touching. One shopkeeper in Jaffa, Israel, hung Canadian flags in his store window for years. He had escaped from Syria thanks to Judy and was hoping she might walk by one day so he could thank her. When she did, he wept and gave her a handcrafted box to show his gratitude.

Multiply that by thousands of families who owe their freedom or their very lives to her secret phone calls, bribes, and smuggling routes, and you get a glimpse of the incredible impact she’s had.

Judy’s story is an example of one Canadian stepping up when no big institution would. Governments at the time were paralyzed or focused on the Soviet Jewry crisis. Very few even realized the scale of the nightmare in Syria.

Judy wasn’t a special agent. She didn’t have diplomatic immunity or large sums of government money. She was a “regular” Canadian who understood that people were in danger and they deserved a chance to be saved.

This story shows that determined individuals can sometimes outsmart oppressive regimes, especially when they find courageous partners on the inside. The rescues also shed light on how quickly a community can be isolated if politicians want it that way.

The Jews of Syria dated back centuries before Canada even existed, yet by the 1990s, their entire future depended on sneaking out. Judy’s success was partly about shining a spotlight on what was happening and quietly pressuring the regime through every bribe or border crossing.

Each person who escaped made it a little easier for the next, because the regime lost a bargaining chip.

You might also draw hope from the fact that a volunteer network, operating for nearly 30 years, pulled off thousands of escapes without losing a single person. That required caution, grit, and nerves of steel, but it happened.

Today, Syria’s Jewish population is close to zero. A once-thriving community is gone from its ancient homeland. On the other hand, they’re safe.

Many are raising children and grandchildren in Israel, the United States, Latin America, or here in Canada. As Judy herself has said, she prevented a potential mass tragedy. Later events in Syria, such as the civil war, could have spelled a far worse end if that community had still been locked inside.

We might also consider the modern parallels.

There are still groups worldwide who are suppressed by governments that want to keep them hidden or powerless. Judy’s legacy shows that one determined person can come up with bold ideas and act on them.

In a sense, it’s a call to each of us: if you see an injustice and feel like you have no authority to fix it, remember that Judy was a mother of three with a love of music and no “official” power. Yet she proved unstoppable when it came to saving lives.

Finally, this story is an example of Canada’s ongoing role in humanitarian efforts. It’s a reminder that we, as Canadians, have a history of stepping in when others look away.

Whether it’s hosting refugees, engaging in peacekeeping, or pushing for human rights, we often do so quietly, behind the scenes.

Sometimes history unfolds in big headlines, and sometimes it happens in secret corridors—through quiet heroes like Judy Feld Carr, a Canadian who refused to let an entire community vanish from the face of the earth.

I hope you find as much inspiration in her story as I do. Thank you for reading and for joining me in celebrating another amazing Canadian contribution that made a world of difference.

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story:

https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/1027071/jewish/Buying-Lives.htm

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jews-of-syria

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/carr-judy-feld

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judy_Feld_Carr

https://premierespeakers.com/speakers/judy-carr

https://aish.com/saving_syrian_jews/

https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/carr-judy-feld

https://blog.nli.org.il/en/damascus_crown_keter/

https://www.biblestudentarchives.com/documents/JudyFeldCarr.pdf

https://www.gg.ca/en/honours/recipients/146-8087

https://www.jewishfoundationtoronto.com/book-of-life-stories/-00carrjudy

https://wizonsw.org.au/women_of_influence/64-judy-feld-carr/

https://nationalpost.com/news/world/israel-middle-east/judy-feld-carr-syria

What a great story! Had no idea. Incredibly brave getting them out and not lost anyone!

The post details the beginning..but still how she managed to start is Amazing, getting in touch, finding the right people. And this was all done without internet.