The Devil's Brigade: How Canadian-American Commandos Changed WWII Special Operations

The untold story of the elite First Special Service Force that scaled impossible cliffs and "owned the night"

The icy wind cut through the dark boot polish and burnt cork that blackened their faces as they silently scaled the sheer cliff face of Monte La Difensa, Italy, one fateful winter night in 1943.

Fingers numbed and bleeding, ropes biting into raw palms, the men of the First Special Service Force inched upward through the December darkness with stealth and determination.

Not a word was spoken between the American and Canadian brothers-in-arms. Just the distant thunder of Allied artillery masking their approach.

Six hundred feet below, the rest of the Allied forces waited.

Six hundred feet above, German machine gunners stood watch, convinced that no military force would dare attempt this "impossible" climb.

They were wrong.

As dawn broke over the Italian mountains, the Devil's Brigade would unleash hell from a direction the enemy never expected, forever cementing their legacy as one of World War II's most daring and effective fighting units.

Hi there. I’d like to share something that I find both inspiring and deeply important for us to remember: the story of the First Special Service Force (FSSF), often called the “Devil’s Brigade,” a unique Canadian-American commando unit in World War II.

Canadian soldiers were a key part of this group, and they fought in some of the most difficult, high-stakes operations of the entire war.

Let’s explore how they were formed, where they fought, and why their story still resonates today, especially when we talk about Canadian international contributions and partnerships.

In the dark early days of WWII, when the outlook for the Allies was grim and uncertain, Allied planners came up with this radical idea to create an elite combined commando force of Americans and Canadians who could fight in just about any environment. Soldiers who were specially trained to make attacks on enemy areas that are known to be extremely dangerous or difficult to attack.

This unit would ideally parachute into Nazi-held Norway to sabotage hydroelectric plants, but also be ready to strike in the mountains of Italy or on the beaches of the Balkans.

It was originally known as Project Plough.

On July 9, 1942, this vision started to take shape with the official activation of the First Special Service Force (FSSF) at Fort William Henry Harrison, near Helena, Montana.

Two men were put in charge of this new force. The first was Lieutenant Colonel Robert T. Frederick, a U.S. Army officer and West Point graduate. The second was Canadian Lieutenant Colonel John G. McQueen, reflecting the group’s binational partnership.

From the start, it was an incredibly diverse, rugged group of volunteers.

American recruiting notices called for

“Single men, age 21–35… Occupations preferred: rangers, lumberjacks, northwoodsmen, hunters, prospectors, explorers, and game wardens.”

Up here in Canada, about one-third of the FSSF’s manpower came from trappers, miners, farm boys, and other men with hardy, outdoor backgrounds. Many of them didn’t even know what they were signing up for because of the secrecy about the unit. Even the trains that brought them into the training facility had their windows blacked out so the men couldn’t see their destination.

Overall, the unit ended up with around 2,300 men (1,800 as combat troops and a service/support battalion). It was organized into three small regiments, each with two battalions of three companies, along with support units.

Once they arrived at Fort Harrison, the men found themselves in an extreme training environment. Days started at 4:30 a.m. with reveille blasted by bugles and, on some mornings, Canadian bagpipers.

The commandos were required to be at peak physical fitness. That meant their training regularly consisted of forced marches up to 97 kilometres (60 miles) at a time, and one entire regiment is said to have finished such a long march in just 20 hours.

They also became familiar with many different weapons, from standard Allied rifles to captured enemy German arms, and practiced intensely with each of them until they could fire and break them down like pros.

For close combat, they were put through their paces by a tough instructor named Pat O’Neill, a former Shanghai police officer who taught them how to use knives as well as their bare hands in quick, ruthless ways. The American Colonel Frederick introduced the men to a stiletto-style V-42 combat knife, specifically designed for this fighting Force.

Training soon evolved to focus heavily on winter and mountain warfare as winter set in. Norwegian ski experts were brought in to teach the men how to move smoothly across snowfields and how to survive in sub-zero weather.

By day, the men scrambled up steep cliffs in Montana; by night, they practiced demolitions and other stealth missions on frozen slopes.

Initially, the FSSF was supposed to go to Norway to strike Nazi hydro plants, but as the war changed, that plan was cancelled. By late 1942, the Germans had fewer critical operations in Norway than initially feared.

The hydroelectric facilities (particularly those connected to heavy water production, which was thought to support a German atomic bomb project) were still targets of concern, but they were no longer considered worth the extreme risk of a full commando parachute operation. Especially one that would likely lead to high casualties and uncertain success in a remote, heavily fortified area.

So the Force kept training and gaining even more mastery of their skills. When spring arrived in 1943, they moved to Camp Bradford in Virginia to add amphibious assaults: rubber-boat operations and beach landings, to their long list of specialized skills.

By the time their grueling training wrapped up, every soldier was a qualified parachutist, mountain fighter, expert in small arms and hand-to-hand combat. This group of fighters was as fit and specialized as any unit in the Allied armies. And now, they were ready for action.

Then they got their first chance to prove themselves that summer.

The Aleutian Islands in Alaska had been invaded by Japanese troops, posing a threat on North America’s doorstep. That’s where the FSSF got its first real test: Operation Cottage, the invasion of Kiska Island.

Every one of the commandos braced for a bloody battle as they headed towards the West Coast. The Japanese had heavily defended a sister island, Attu, and it took an intense campaign for the U.S. Army and Canadian forces to capture it. So the FSSF expected the same at Kiska, where some believed 5,000 entrenched Japanese troops were lying in wait.

On August 15, 1943, the Force landed alongside 32,000 or so American and Canadian soldiers, in the middle of the night, equipped with cold-weather gear and an arsenal of weapons.

They crept ashore in dense fog, expecting fierce resistance.

But in a surprising anticlimax, the Japanese had secretly left two weeks earlier under the cover of poor visibility.

So after 48 hours of difficult progress across the island’s rugged terrain, the FSSF and the other Allied troops took Kiska practically without a fight.

However, the mission wasn’t as safe as it sounds. The biggest threats turned out to be from Japanese landmines, booby traps, friendly fire incidents, and vehicle accidents in the thick fog.

Tense Allied troops, not aware the Japanese were gone, sometimes misidentified each other in the low visibility, leading to tragic shots exchanged among friends. A handful of FSSF men were also injured from accidents in the rough terrain or harsh weather. By the end of the mission, tragically, 300 men had lost their lives.

The troops were devastated. With all the anti-Canadian US sentiments and anti-US Canadian sentiments we hear these days, try to imagine that not that long ago we all were destroyed by the thought that we had accidentally hurt and killed each other. It was, and rightfully should’ve been, utterly devastating to everyone involved.

For all of the tragedies involved with Operation Cottage, it did give the Force invaluable experience in amphibious landings and cold-weather living. They built small field camps on Kiska and continued to perfect their patrol and logistical skills in a harsh climate.

Of course, that doesn’t bring back the brave men who lost their lives during that mission.

In November 1943, the FSSF was ready for its next test and arrived in Italy, where the Allies were trying to push north toward Rome. But progress was stalled by well-fortified German defensive lines in mountainous terrain known as “the Winter Line.”

One of the toughest points in these lines was Monte La Difensa. At nearly 960 metres (3,000 feet), this rocky peak guarded a crucial corridor called the Mignano Gap. German forces had already shrugged off repeated attacks by the British, Americans, and Canadians here.

By the time the FSSF arrived, Allied troops had pummeled La Difensa with over 200,000 artillery shells, but the German forces on top, the 104th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, still held tight.

People started calling it “Million-Dollar Mountain” after all the ordnance wasted on it. A major Allied operation called “Operation Raincoat” assigned the FSSF the daring job of climbing Difensa’s steep northern cliff to mount an attack from there. Something the Germans believed no one would dare try.

If the Force succeeded, they’d potentially crack the Winter Line.

On December 2, 600 men of the FSSF’s 2nd Regiment gathered quietly below the mountain. That evening, Allied guns unleashed a massive barrage, pounding Difensa and masking the noise as the Forcemen began moving.

By 10:30 p.m., they reached the base of the sheer cliff face. In small groups, lead climbers like US Staff Sgt. Howard Ausdale and Canadian Sgt. Alistair Fenton, the commandos free-climbed under the cover of darkness, quietly anchoring ropes.

Then, one by one, men hauled themselves up, carrying nothing but weapons and some ammo. No heavy packs that could slow them.

By around 1:00 a.m. on December 3, the first wave reached the top undetected.

Over the next couple of hours, the entire 1st Battalion (roughly 600 men) formed up on the summit plateau, behind the German defenders who had barely posted guards on the north side because they believed it was unclimbable.

At first light, something alerted the Germans. Possibly a rock clattering or a sudden movement, and they sounded the alarm.

Flares lit the battlefield.

German MG-42 machine guns began firing.

The FSSF men responded with a furious charge and hand-to-hand fighting, including bayonet strikes and grenades. One soldier recalled hearing screams echo across the rocky summit.

Though caught by surprise, the Germans were disciplined troops who fought back fiercely. Some even faked surrender to lure Forcemen in close, where they thought they could sneak attack them when the Allies let their guard down.

The fight raged in pockets across the summit.

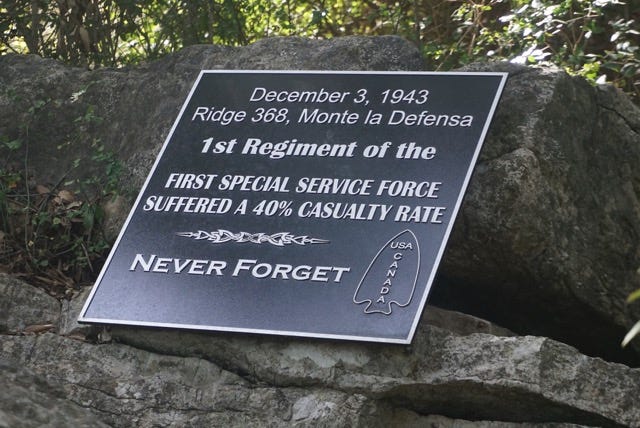

By around 7:00 a.m., the FSSF had overrun Monte La Difensa’s peak, but at a high cost.

Many were dead or wounded, and they began to brace themselves for counterattacks. The Force’s momentum eventually carried them toward the neighbouring peak, Monte La Remetanea, but their beloved battalion commander, Canadian Lieutenant Colonel Thomas MacWilliam, was killed by a mortar round.

Colonel Frederick himself then came up the mountain to direct the final push.

Over the next couple of days, the Forcemen held Difensa’s summit against multiple German attempts to retake it. Then on December 5, they attacked Remetanea and captured it as well.

And by December 6, the entire Camino ridge system, including La Difensa, was under Allied control.

This victory opened a key section of the Winter Line and marked the first real combat test for the FSSF. The cost was steep. They lost around 25 percent of their men in that action alone.

By mid-January 1944, after over a month of continuous fighting, they were down from 1,800 men to under 500 effective soldiers. But their mountain-climbing tactics and raw courage gave the Allies something no other unit had managed: a swift capture of a fortress-like position. And an important victory in an extreme situation where the enemy had the strategic high ground.

La Difensa became legendary in FSSF lore. There’s even a 1968 film, The Devil’s Brigade, whose climactic sequence is based on this battle.

Their success proved that the unique value of this specialized Canadian-American unit had paid off. Through their night infiltration and cliff scaling training, they were able to capitalize on an element of surprise.

US General Mark Clark, who had selected the Gorce for this daring campaign, praised their “outstanding bravery and skill,” and now knew what a tremendous asset they were.

Soon, the battle-tested Force would be called upon again for another grueling mission.

Not long after breaching the Winter Line, the Allied campaign in Italy was stalled again. This time near a rocky hill called Monte Cassino. The high command launched an amphibious landing at the coastal town of Anzio, hoping to bypass German defenses inland and get closer to Rome.

The FSSF, suffering massive casualties from their mountain battles, was still somehow thrown into the thick of it. The survivors from the winter line campaign were joined by the rest of the FSSF that had been held back in reserve, and around 1,200 FSSF commandos arrived at Anzio in early February 1944, ready to give it Hell.

After their arrival, they took over a 13-kilometer stretch of the beachhead’s perimeter along the Mussolini Canal, replacing American Rangers who had just been decimated there.

Though severely understrength, newly promoted Brigadier General Robert T. Frederick believed that aggression was the best defense. He confidently told his men they would “own the night,” and then they got to work.

Each evening, small squads paddled across the canal, slipped through barbed wire, and raided German positions.

They cut telephone lines, ambushed patrols, and occasionally snatched prisoners for intelligence.

Their movements in the darkness and stealth maneuvers were so effective, some German soldiers began referring to their foes as “Die Schwarzen Teufel”—the Black Devils.

It was through reading diary entries of fallen German soldiers that the Force became aware of the label, which they immediately embraced, hence why we now remember them as “the Devil’s Brigade.”

If it helps to understand the terror our men inflicted, picture a five-man patrol led by Lieutenant T. Mark Radcliffe, crawling through the swampy edges of the Mussolini Canal under a moonless sky.

They’re in black coveralls, faces smeared, carrying the distinctive V-42 dagger and submachine guns. At the right moment, they launch a swift ambush on a German patrol, firing silenced pistols and tossing grenades.

They cause panic, grab a wounded German captive, then slip back across the canal, prisoner in tow.

This sort of nightly harassment built the FSSF’s fearsome reputation at Anzio. The calling cards they’d leave behind: little notes with the FSSF insignia and the inscribed German warning “Das dicke Ende kommt noch” (“The worst is yet to come”) ratcheted up the psychological pressure.

Large German units fretted about infiltration by the shadowy figures that crept around each night. They worried so much about the enemy they couldn’t see that they withdrew some outposts, figuring they were up against a much larger force because of their opponent’s effectiveness.

For 99 days, the Devil’s Brigade held the line, enduring artillery barrages, slogging through muddy marshes, and fighting off repeated German probes. Buying the Allies the critical commodity of time without giving up an inch of coastal soil.

Then, on May 23, 1944, the Allies were finally prepared to launch a full-scale push forward from Anzio.

After three days of intense fighting, the Allies smashed through the German defenses. Instead of taking time to catch their breath, the Force joined the push toward Rome, capturing key hills and then racing into the city as some of the very first Allied troops to arrive on June 4, 1944.

That dash into Rome sealed their legend as the unstoppable “Devil’s Brigade.”

But this campaign again left them depleted. General Frederick himself was wounded multiple times but refused to leave until absolutely necessary. By now, the entire unit was running on sheer grit. But they had proven themselves indispensable. Mountains? Amphibious landings? Night raids behind enemy lines? They could do it all.

The Allies next turned their attention to southern France in Operation Dragoon (August 1944). The FSSF found itself reshuffled and strengthened a bit, with fresh recruits raising their numbers back to around 2,000.

Now commanded by Colonel Edwin Walker (an American who had replaced Brigadier General Robert T. Frederick because Frederick was promoted and re-assigned to a bigger role), the Force prepared to land on the Mediterranean coast and neutralize German coastal batteries there.

Shortly before the main Allied invasion force landed in southern France, the Devil’s Brigade took on two small islands, Île du Levant and Port-Cros, which had German artillery that could bombard the Allied ships and sink the invading forces before they could launch a full-scale attack.

Under darkness, FSSF soldiers landed on Port-Cros by rubber boats and small craft.

At dawn on August 15, they attacked old stone forts held by about 120 German troops. They went fort by fort, using grenades, bazookas, and close-quarters fighting to drive defenders out.

After some fierce firefights, the remaining German holdouts faced naval gunfire from U.S. destroyers that could now position themselves close enough to get in the fight.

That broke the German resistance, and they surrendered by mid-afternoon. Five forts fell to the FSSF, and more than 100 German prisoners were taken. The Force suffered casualties as well, and at least 9 of its men were killed.

Once the islands were secured, the Devil’s Brigade rejoined the main invasion of southern France. They helped push eastward along the French Riviera and up into the Alps near the Franco-Italian border.

In early September, they fought at L’Escarène in the Maritime Alps, surrounding and capturing a whole German battalion of around 1,000 men.

By November 1944, they were still patrolling those chilly high mountain passes, occasionally skirmishing with German rear guards. But the war was now clearly turning in the Allies’ favour, and the FSSF had played a major part in that.

By December 1944, the end was in sight for the First Special Service Force. Casualties and constant frontline deployments had whittled them down.

Replacements didn’t have the same special training as the original volunteers. The Army often also used them as standard light infantry, meaning their unique capabilities weren’t always central to missions anymore.

On December 5, 1944, near Villeneuve-Loubet in southern France, the Force was formally disbanded.

It happened in a modest field ceremony. Canadian troops stood in ranks as their American brothers marched past in salute. After everything they’d been through together, there was no grand goodbye. Just orders given and received, bags packed, and a quiet parting of ways.

Canadians were often reassigned to the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion or other Canadian units. Many Americans joined the 82nd or 101st Airborne, some to Ranger battalions, others forming the heart of the new 474th U.S. Infantry Regiment.

Though the FSSF only existed for about 18 months, it had an immense impact. By war’s end, it reportedly accounted for around 12,000 enemy casualties and took over 7,000 prisoners, a remarkable achievement for a force that numbered fewer than 2,000 at full strength.

It also suffered around 2,700 total casualties, meaning it had to be refilled multiple times over. Yet as brave men from the U.S. and Canada paid the ultimate price for our freedom, fighting side by side, the Force never failed a mission or lost an objective it set out to capture.

Their example of specialized, highly trained soldiers executing daring raids and infiltration missions laid the groundwork for modern special forces units. In the United States, the Army’s Special Forces, known as Green Berets, trace direct lineage and heritage from the FSSF.

That’s why the arrowhead shape of the FSSF patch is still reflected in the U.S. Special Forces crest, complete with the V-42 fighting knife that Colonel Frederick designed.

Each December, American and Canadian special forces mark “Menton Day” (named for where the Force operated in southern France near Menton) to celebrate this shared heritage and the FSSF’s impressive feats of valour.

In Canada, the unit’s influence helped lead to the development of Joint Task Force 2 (JTF2) and the Canadian Special Operations Regiment (CSOR). In essence, the Devil’s Brigade showed that Canadians could excel in small, elite commando teams, just as well as, or better than, any other country’s soldiers.

Military historians in Canada see the FSSF as the forerunner to the special operations capabilities the country has now. In 2015, the U.S. Congress awarded the entire FSSF the Congressional Gold Medal, underscoring how both nations still regard the Force as a symbol of friendship, bravery, and remarkable service in the face of evil.

Even though the First Special Service Force stopped existing as a distinct unit in late 1944, its memory lives on. The “Devil’s Brigade” moniker was well-earned, forged by nighttime raids at Anzio, brutal climbs in Italy, and amphibious assaults in frigid waters.

Our Canadian soldiers served side by side with Americans in an outfit that took on some of the toughest missions and gave the Allies a unique edge.

Their success shows the power of bringing together volunteers from different regions who share a common spirit of adventure, toughness, and willingness to learn specialized combat skills and endure some of the most gruelling missions of WWII.

Today, whenever you see or read about Canadian special operations units or watch some of the ceremonies honoring past war heroes, remember that a big part of that history goes back to the men who trained in the mountains of Montana and fought through Italy and France under the patch of the First Special Service Force.

They demonstrated that Canadians could fight in the harshest conditions and innovate in ways that even hardened enemy soldiers did not expect.

Over the decades, books, documentaries, and even Hollywood films (like The Devil’s Brigade from 1968) have kept the memory alive. And if you talk to modern Canadian or American special forces members, they might tell you about Menton Day, or show you the arrowhead badge.

That’s the spirit of the FSSF living on.

The true legacy of the First Special Service Force is that it was a groundbreaking partnership between Canada and the United States during a global crisis.

Their training, missions, and achievements read like an epic war story, but it’s all grounded in real events and involved real, ordinary, everyday people.

That’s why the Devil’s Brigade deserves to be more than just a footnote in the larger WWII story. It’s a true example of Canadian courage and adaptability, and a clear reminder of what’s possible when nations stand together as allies.

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story:

https://armyhistory.org/first-special-service-force/

https://greydynamics.com/the-devils-brigade-tales-of-the-first-special-service-force/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Special_Service_Force

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/world-war-ii/first-special-service-force.html

https://valourcanada.ca/military-history-library/devils-brigade-fssf/

https://arsof-history.org/first_special_service_force/war.html

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/what-the-devils-brigade-did-in-world-war-ii/

https://legionmagazine.com/the-devils-brigade/

https://arsof-history.org/first_special_service_force/legacy.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Devil's_Brigade

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/first-special-service-force

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special_Service_Force

https://canadianbattlefieldtours.ca/devils-brigade/

https://www.canadiansoldiers.com/organization/specialforces/1ssf.htm

https://soaa.org/the-devils-brigade/

https://montanamilitarymuseum.org/the-first-special-service-force/