Between the Cracks: The Enduring Legacy of The Rheostatics

How a band that never quite fit in became essential to Canadian music

It's a frigid February night in 1992, and you're packed into a sweaty, smoke-filled club in downtown Toronto. The air smells of spilled beer and damp winter coats thawing under the stage lights. The crowd—a mix of art students, music nerds, and curious locals—suddenly erupts as four unassuming guys take the stage.

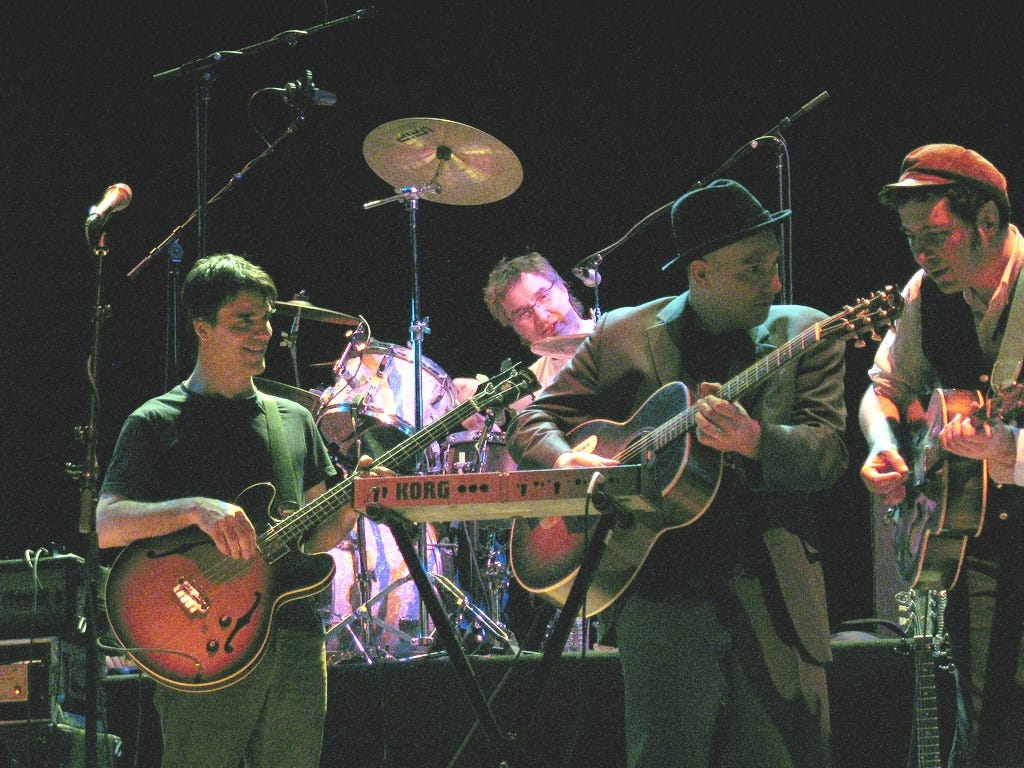

One of them, Martin Tielli, looks almost painfully shy as he adjusts his guitar strap. Dave Bidini, wearing what appears to be a thrift-store hockey jersey, grins and nods to the crowd. Tim Vesely hunches over his bass, quietly focused, while Dave Clark settles behind his drum kit, ready to unleash controlled chaos.

And then it happens: they launch into "Saskatchewan," a song that somehow turns the vast emptiness of prairie winters into a soaring anthem. The music swells from delicate to thunderous as Tielli's otherworldly voice cuts through the haze. Strangers turn to each other with that look—half-smile, half-disbelief—that says, "Are you hearing what I'm hearing?"

This is The Rheostatics in their prime: a band creating something that feels wildly experimental yet undeniably Canadian, something that makes you want to both analyze the lyrics and pump your fist in the air.

In this moment, nobody cares that they'll never be on the cover of Rolling Stone. Everyone in this room knows they're witnessing something special—a band that's rewriting what Canadian music can be, one bizarre, beautiful song at a time.

Hello again, and welcome back to our weeklong journey celebrating Canadian music. Today, we’re talking about The Rheostatics, a band that many fans and critics argue is one of the most important Canadian bands of all time.

Whether you’ve followed them for decades or never heard of them until now, I believe their story will surprise you.

Let’s begin with a simple fact: The Rheostatics have been called “iconoclastic icons.” If that sounds like a contradiction, it’s because this band has always existed between the cracks of classification.

They have been described as prog-rock, art-rock, or even “orchestral psychedelia.” And yet, they’ve also been hailed in multiple polls as creators of two of the greatest Canadian albums ever recorded: Melville (1991) and Whale Music (1992).

It’s unusual for a group that never had widespread commercial success in the pop sense to be considered so fundamental to our country’s musical heritage, but the Rheostatics somehow pulled off that balancing act.

Guitarist Dave Bidini once said that Canada has a reputation for being “cavalier” in literature and film, always testing the limits, so why can’t our music be the same?

This restless energy has been part of the Rheostatics’ DNA since their beginnings in Etobicoke, Ontario in 1978. They formed as teenagers, in a basement, with big dreams and a willingness to try anything.

If you travelled back to the late 1970s, you’d see a teenage Dave Bidini (guitar), and Tim Vesely (bass) jamming out to an eclectic mix of musical influences as they experimented to see what sounded cool, but also was fun to play.

In 1980 Rod Westlake (drums), and Dave Crosby (keyboard) joined the band and they gelled fairly quickly although they all had very different ideas of what they wanted to play and what inspired them to want to get on stage and perform in front of live audiences.

Later that year, the band got its first gig. It’s a famous anecdote, that the band had to get special permits to play clubs back then because they were all underage and not typically allowed to be in the establishments with the stages where they wanted to be on.

Those first years were exciting, but anything but smooth. Westlake left soon after the band’s initial show and was replaced by drummer Dave Clark. In 1981 Crosby left. But the group kept gigging and experimenting.

In 1983, they added a horn section and started calling themselves “Rheostatics and the Trans-Canada Soul Patrol.” Clark had met some horn players while taking a jazz summer class and convinced his bandmates to let them join. Imagine the youngsters hauling around a horn section for funky R&B-influenced shows at downtown Toronto clubs.

It’s far from the music they would later become known for, but it’s a reminder of how you can start in one place and end up somewhere completely different.

By 1985, the horn section fell away as the band switched to a more alternative/rock style. When guitarist and singer Martin Tielli joined, he injected another layer of creativity. Tielli and Clark had previously played together in a band called Water Tower.

Tielli could be a “complete buffoon” one moment, then break your heart with a shimmering guitar lead the next. He and Bidini would alternate lead vocals and songwriting, and that rotating spotlight became a hallmark of the Rheostatics sound.

When the horn section left, the band had also dropped the “Trans-Canada Soul Patrol” part of their name and stuck to the simpler “Rheostatics.” But even as they morphed into a guitar-bass-drum lineup with Tielli aboard, they were still in no rush to “fit in” to any one particular genre or sound.

They’d play an indie-rock style tune on one track, a folk love song on the next, and then an all-out free-form jam that sounded more like performance art just because they felt like it.

Somehow it all felt Canadian, even if we can’t pin down exactly why. As Tielli put it, perhaps it’s this “fragility, complexity, and sense of borrowing from all over” that gives them a distinct national spirit.

After building a name for themselves during the early 80s, the band was ready to record their first album, which they famously titled Greatest Hits, and released in 1987. A cheeky move for an unknown group that endeared them with their small but loyal fanbase.

Only 1,000 copies of that album were pressed, so it’s more of a collector’s gem now than anything else. But, if you dig into it, you’ll hear a rough version of what they were about to become: odd lyrical perspectives, some “Canadian dream” references, a partial comedic tilt, and tributes to our national game (hockey) via “The Ballad of Wendel Clark, Parts I and II.”

Around this time, they also discovered the thrill of cross-country touring. They’d load up a van with instruments and sweaty hockey jerseys, venture into places like Thunder Bay and Vancouver, meet local bands, and sleep on strangers’ floors.

On one such road trip, a 19-year-old Martin Tielli found himself overwhelmed by the new people, new experiences, and wide-open spaces of the prairies. He’d later channel that inspiration into the songs that would form the backbone of the album Melville.

But before that album would come together, Tielli briefly left the band in 1988 after one too many disagreements, and the group basically disbanded for a year.

Some of them tried to form other bands, others took short-term gigs. But eventually, they reunited at the Rivoli in Toronto for a performance. Immediately it was evident that the spark was still there.

So Tim Vesely, Dave Bidini, Dave Clark, and Martin Tielli decided to push forward together as the Rheostatics once more. When they started jamming together again, they realized their music was more interesting and lively than ever.

They’d outgrown their earliest funk experiments. This was a new version of the Rheostatics. One that was playful, adventurous, and anchored in “Canadiana” references. They recorded a quick demo together in 1989 that morphed into their second album, Melville (1991).

It arrived four years after Greatest Hits, and many critics considered it a quantum leap forward. One radio-friendly track, “Record Body Count,” got them noticed on MuchMusic, while “Northern Wish,” “Saskatchewan,” and a cover of Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” made them into local heroes of “songs about Canada.”

Long before “regional references” became trendy outside of folk music, the Rheos were singing about the length of the winters and the heartbreak of the prairies.

If you talk to longtime fans, they’ll tell you that Melville is essential listening for any Canadian music lover. When the band recorded Melville, they enlisted producer Michael Phillip Wojewoda, who had worked with an array of inventive groups.

The sessions at Reaction Studios in Toronto were buzzing with excitement, because the band had a pile of new material that was both melodic and eccentric. And that excitement can be felt throughout the album.

The track “Northern Wish,” was co-written by Bidini’s then-future wife, Janet Morassutti, who brought her own style to an ever-increasing array of influences and experimentation.

Listeners loved how the band managed to be silly and heartfelt seemingly all at once. One minute they’d be referencing hockey players, and the next they’d be singing in French about not caring if they became popular in the U.S. This proud, offbeat stance left an impression on critics too, especially those looking for a unique Canadian sound.

Then came the album Whale Music in 1992, widely considered to be their masterpiece. It was loosely inspired by Paul Quarrington’s novel of the same name: a story about a reclusive musician, reminiscent of Brian Wilson.

The Rheostatics took the creative spark that ignited Melville and their tour the year before and delivered a record that brims with oddball humour, heartbreak, long jammy sections, and artful lyrics.

Songs like “California Dreamline” or “Dope Fiends and Boozehounds” captured a dizzying swirl of influences, from folk to psychedelic, to straight-up rock.

Even Rush drummer Neil Peart got involved, which was a pretty big deal. Bidini had interviewed Peart for an article, and the conversation led to the Rheostatics inviting him to guest on a couple of tracks, including a piece featuring an epic poem and drum solo by Dave Clark.

This cameo by a Canadian rock legend only added to the sense that the Rheostatics were worth paying attention to.

But here’s the funny part: despite the critical acclaim for Whale Music, the band was more or less broke. They had a legion of diehard fans who would drive hours to see them, but large-scale commercial success always remained elusive.

But Dave Bidini shrugged that off, saying it was more important to “make connections” than to pack arenas.

However, after Whale Music caused a stir among critics, the Rheostatics found themselves signed to a major label: Sire Records from 1993 to 1995. You might think that a major-label deal would catapult them to huge commercial fame, but, in their case, it was an odd match.

They were asked to record music for the Whale Music film adaptation, which led to a 1994 soundtrack album called Music from the Motion Picture Whale Music. The single from that project, “Claire,” became the Rheostatics’ only ever Top 40 hit.

“Claire” was a total assignment. The band wrote it specifically as the “love song” for the main character in the film. Tim Vesely came up with the gentle melody and lyrics, and it ended up winning a Genie Award for Best Original Song.

Although that success hinted that the band could be veering onto a more mainstream path, it also created tension. Drummer Dave Clark openly disliked the track and felt it steered them toward a pop style that betrayed the Rheostatics’ adventurous identity.

Regardless, the single’s popularity introduced them to a wider crowd, including folks who normally wouldn’t gravitate to a band best known for referencing the Group of Seven or hockey heroes in their lyrics.

In 1994, Sire released their next album, Introducing Happiness, which combined catchy pop elements with the group’s usual weirdness. For example, you’ll hear a fairly straight-ahead track like “Claire” next to something bizarre like “Fan Letter to Michael Jackson.”

This back-and-forth can be disorienting for first-time listeners. Even the band jokes that their albums feel like compilations from multiple groups. Sadly, Sire found them difficult to market and let them go just as the Rheostatics were about to embark on a major cross-Canada tour.

Right before that tour, Dave Clark also quit. He was replaced by Don Kerr, a friendly drummer who had recorded them at the Gas Station studio in Toronto.

Kerr’s style was more straightforward, giving the band a fresh spark. But fans who adored Clark’s unpredictable drumming found the switch a bit jarring. Even so, the band soldiered on. Their short mainstream moment ended, and they returned to the independent scene with a renewed focus on making the music they wanted.

As 1995 wore on, the Rheostatics were asked to do something only they could do: compose music for an art exhibit celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Group of Seven.

That led to Music Inspired by the Group of Seven (1996), a mostly instrumental album, composed with help from pianist Kevin Hearn and even some recorded dialogue clips of Mackenzie King and other historical Canadian figures.

They performed these compositions in the National Gallery in Ottawa, an unlikely venue for a rock band, but a perfect playground for the Rheostatics’ creativity.

The project underscored how they were never just a rock group; they were culture-hungry explorers ready to link up with Canadian myths, landscapes, and visual art.

During this era, the band picked up a plum opening slot for The Tragically Hip. On tour with the Hip, they brought their unorthodox brand of music to bigger arenas, and although they didn’t suddenly become a pop-radio fixture, they did find a new wave of diehard fans.

Gord Downie publicly praised them too. To this day, you can hear Downie’s onstage shout-out on the live Hip album Live Between Us (1997): “This is for the Rheostatics—we are all richer for having seen them tonight.”

After the tour with the Hip ended, the Rheos were back on their own turf in Toronto, where they produced The Blue Hysteria (1996). If you’re wondering whether they tried to repeat the success of their Top 40 Hit “Claire,” the answer is heck no.

Instead, they doubled down on socially aware songs, like “Bad Time to be Poor,” a dig at the Ontario government’s funding cuts. That single actually did get some radio play, making it the only other Rheostatics track (besides “Claire”) to chart. Meanwhile, the album as a whole was eclectic, with everything from scathing rockers to gentle folk-inspired moments.

Then came Double Live (1997), a sprawling set of recordings from different venues that ranged from in-store gigs to giant arenas. It remains a fan favourite for capturing how their live shows roamed freely between tight song structures and open-ended jams.

That same year, they also recorded The Nightlines Sessions, featuring performances from the final broadcast of CBC Radio Two’s Night Lines.

But their most offbeat project was The Story of Harmelodia (1999). Dave Bidini wrote a children’s tale about Dot and Bug, two siblings who tumble into a world called Popopolis.

The album weaves songs with narration by Bidini’s wife, Janet Morassutti, and includes whimsical artwork by Tielli. It’s part kids’ fable, part musical experiment. For some, it’s an introduction to the Rheostatics’ gentler side. For others, it’s further proof that they never wanted to stay in one lane.

In the early 2000s, the Rheostatics moved to Perimeter Records for Night of the Shooting Stars (2001). Don Kerr played drums on the album but left the band right after. Michael Phillip Wojewoda, their longtime producer, stepped in as drummer.

The annual “Fall Nationals” at Toronto’s Horseshoe Tavern became a main event for fans. It was a week or more of consecutive gigs, each one unique. Performances from these residencies turned into albums like Calling Out the Chords, Vol. 1.

They released 2067 in 2004 through True North Records. It was a concept of sorts, imagining Canada 200 years after Confederation. The single “Marginalized” got modest airplay, and “The Tarleks” (inspired by the WKRP in Cincinnati character Herb Tarlek) even featured that show’s actor Frank Bonner in the music video.

Despite a loyal audience though, the group found themselves at a crossroads. Tim Vesely eventually decided to focus on side projects, and by 2007, the band announced their farewell concert at Massey Hall on March 30.

It was their biggest headlining venue and a deeply emotional night. CBC Radio 2 broadcast it soon after. For many of us who listened, it felt like the end of an era. The band parted ways, each member drifting to new musical or personal adventures.

But after almost three decades of making Canadian music about Canadian topics, it should come as no surprise that The Rheostatics never vanished completely.

They played a few special reunion events over the years, then reformed more officially in 2016, adding Kevin Hearn and Hugh Marsh to the mix. They debuted fresh tunes like “Music Is the Message” and “Mountains and the Sea.”

In 2019, they released Here Come the Wolves, their first new studio album in 14 years. If you give it a listen, you’ll hear that same can-do-anything approach from their earlier days, plus the sense that they’re more comfortable than ever with who they are.

Let’s wrap up with a last thought. The Rheostatics’ story is about a band that followed its own path for decades, often without a flashy spotlight. Along the way, they:

Celebrated Canadian references (Group of Seven, hockey, prairies, French and English lyrics).

Shared songwriting so that fans got multiple voices, styles, and personalities.

Mentored younger acts with events like their “Green Sprouts Music Week” and ongoing support for new talent.

Inspired loyalty in fans who introduced their kids to the music, keeping the fan base alive.

Even though they spent years shuffling through label deals and lineup changes, the Rheostatics stayed true to an outlook that feels deeply Canadian: one that mixes tradition and experimentation, seriousness and silliness, the local hockey rink and the National Gallery.

That’s why many people argue that they’re among the most essential Canadian bands—because they never stopped challenging what a Canadian band could do.

If you ever decide to explore their discography, keep an open mind. One minute, you’ll be laughing at a goofy lyric, and the next you’ll be reflecting on a profound line about love or identity or this huge country we call home.

And if you catch them live—well, don’t be shocked if they slip in a little floor-hockey banter between the jams. That’s just who they are, and it’s part of why they matter.

Thanks for reading. I hope you’ll give the Rheostatics a listen, especially if you love discovering corners of Canadian culture that aren’t always in the mainstream. Let’s keep celebrating our country’s music—both the big names and the wonderfully offbeat ones.

Essential Listening:

Have a rad rest of your day!

Sources used to research this story:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rheostatics

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/rheostatics-emc

https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/rheostatics

https://the-avocado.org/2021/07/02/rheostatics-night-thread/

https://www.rheostatics.ca/band.htm

https://exclaim.ca/music/article/rheostatics-blame_canada

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/rheostatics-mn0000890350

https://www.rheostatics.ca/music.htm

https://www.rheostaticslive.com/staticjourneyvolume1.shtml

https://www.sixshooterrecords.com/artists/rheostatics

https://amplify.nmc.ca/record-rewind-rheostatics-music-inspired-by-the-group-of-seven/

https://www.discogs.com/artist/559525-Rheostatics

https://www.rheostatics.ca

https://www.nicholasjennings.com/rheostatics-rock-in-a-literary-groove

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Del_McCoury

https://www.queensjournal.ca/former-rheostatic-carves-musical-territory/

https://www.rootsmusic.ca/2020/02/08/the-rheostatics-here-come-the-wolves/

https://www.rheostatics.ca/music_discography.htm

https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/arts-and-life/2017/08/19/rheostatics-are-re-introducing-happiness

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-rock-music-explodes

https://www.rheostatics.ca/bidini/pdf/gni_rheobituary.pdf

https://exclaim.ca/music/article/the_rheostatics_reunite_for_toronto_concert